Composer John Massari on 35 Years of ‘Killer Klowns from Outer Space’

Upon its release in 1988, Killer Klowns from Outer Space was perceived as a bit of a riddle, wrapped in a mystery inside a cotton candy cocoon. Vibrant, kooky, and weird, its unique fusion of comedy and horror endeared itself to equally as many folks who found it off-putting. While time is not always kind to some films, distance has only made the hearts of many horror fans grow fonder of this distinctive Chiodo Brothers’ creation. A true practical and visual effects marvel, Killer Klowns now rings in its 35th anniversary, more vital and more appreciated than ever.

One individual who has always preached the Klown gospel is the film’s composer, John Massari. A fan from day one, Massari understood and admired what the Chiodo Brothers were going for and was able to channel and support that vision through his music. Utilizing an array of classic ‘80s electronic synthesizers and technology, Massari crafted a score emphasizing the klown’s otherworldly origins while delicately drafting a balanced tonal atmosphere.

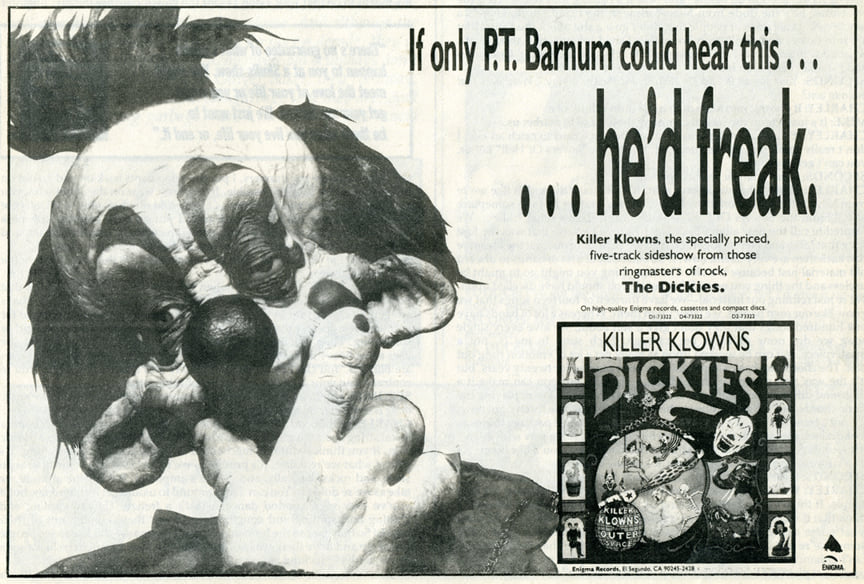

Along with the film’s incredible theme song by L.A. punk icons, The Dickies, the music of Killer Klowns from Outer Space has remained a popular horror fan favorite. Therefore, when Massari and The Dickies started teaming up a few years back for occasional dual-Killer Klowns performances, fans were understandably psyched.

To further celebrate the film’s anniversary and the recent Killer Klowns from Outer Space 35th Anniversary Music Celebration performance in Los Angeles, Dread Central sat down with Massari for a chat. We touch on The Dickies, the fans, the klowns, the Chiodos, the fascinating blockbuster inspiration that influenced this cult classic, and so much more.

Dread Central: You’ve spoken about watching an early score-less Killer Klowns from Outer Space to audition to become the composer. As one of the first to see the film, what were your initial thoughts?

John Massari: It was expertly edited together by Chris Roth. He went by the pacing of the story. He didn’t have any temp music, which was a godsend because you don’t have any predisposition of who likes the temp track and who doesn’t.

So when I saw the movie from the beginning, at first, I said, “OK, it seems like a teen horror movie.” Where teens are played by 20-year-olds or late 20-year-olds. But then, when we have that first scene in the forest, and I see that beautiful spaceship, I said, “Ok, I get it. These guys are really serious. This is really awesome.” It just like, (boom!) appeared. I was very taken, and I think that’s when I fell in love with the movie.

Ray Bradbury, he says, you’ve got to love what you do. So, already, I was on the edge of my seat. And there were scenes in there that, without music, are actually really stark and much scarier. It had the feel of a movie I really admire by Richard Elfman that I’d seen a few years earlier called The Forbidden Zone. It’s so bizarre that people almost don’t understand it. It draws you in.

So, that was my first impression. And then the clowns were just so bizarre. They’re such brilliant creations of the Chiodo Brothers’ imagination, which basically exploded out of their childhood experiences. And then Charlie, who’s such a brilliant genius of an artist, he and his crew concocted all these different characters. It was just fascinating. I really couldn’t sleep that night when they gave me the VHS tape.

They said, “Ok. You have two weeks. Pick a scene that best represents what you think and do that particular scene.” I chose what I call a keystone moment when the characters come into the tent for the first time, discovering that it’s not really a tent and getting chased out by killer klowns. I said, “I have to do whatever I have to do to be part of this movie.” That was my mindset. Steve Chiodo said with that heavy Bronx accent of his, “Well, it looks like you’re the composer for our film!” I was so thrilled when I got the call!

DC: The Chiodo Brothers seem so lovely and joyful. Is that true in real life? When you first met them, was that just the icing on the cake?

JM: Oh, yeah. I was born in New York. We lived in Brooklyn, but we came out to Los Angeles really early on in my life. I’m basically a Californian, although most of my closest family is still in Italy. So I thought to myself, “If I was a kid growing up in my neighborhood, and if these guys lived down the street, we would always have been building model airplanes, blowing them up, or going on adventures.” Or, “Oh, there’s a pile of junk there? Let’s go through it. Whatever they throw away at the construction site, we can build a fort or a spaceship out of it,” you know? That’s the impression that I got from them. To this day, they all still have this curiosity and passion for what they do.

DC: Your music brings such balance to the film. It succeeds in tempering the kitsch and comedy to support the darker elements without losing that joyful Chiodo energy. While you were working on it, was that difficult or more intuitive? How consciously were you trying to make sure that the tone didn’t go too far one way or the other?

JM: I knew I wanted to achieve a certain balance and contrast. The scenes where there are not a lot of notes and things are drawn out can be the toughest scenes to compose music for. You have to really leave space for the scene and then make a subtle move at certain parts.

There’s a scene where Dave and Mike go to where all the kids are making out, and they realize the whole place is covered with cotton candy now. Dave doesn’t know that, so he’s cautiously walking around. You don’t want to make it seem like something’s going to jump out and bite him. But at the same time, you want to let the audience get relaxed enough yet be a little tense with anticipation.

There was one movie that I probably saw half a dozen times, and I went to the theater each time with a little Sony Walkman to record it and then listen to it continually over and over again. I thought the music was positioned so expertly well to build up gags and tension. I could not ignore it. So, that was the first Ghostbusters.

Elmer Bernstein, what a brilliant composer. Wow. Most of his films I really look closely at. Stripes is similar. Ghostbusters had that balance of terrifying but yet it’s funny. I think Killer Klowns has that as well, but maybe a little more toward the dark end. And that’s what the Chiodo Brothers always said: “We don’t want full-on gore.” It’s more cotton candy kills where you maybe see the aftermath, but you don’t see someone really get it. So, from that, I think I learned a lot.

There’s also another composer that I really admire—Burt Bacharach. If you listen to some of his music, he just can’t end a song. He has to start something new at the end. If you ever hear his song, “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head,” it was a bit hit in the late ’60s. You think it’s going to end, then it goes, [sings the end piece of the song]. I used to get so pissed when radio stations would cut that off.

So, I adopted certain things like that where you can just go up, and all of a sudden, boom, you change gears a little bit. Not to the point where it’s so drastic it throws you off. It’s still in the mood. For instance, John Williams does that well.

So when I got to Killer Klowns, I had worked on all kinds of Disney things. I even worked on Little House on the Prairie and cut my teeth working on that with veteran composer David Rose, who had also done Bonanza, Please Don’t Eat the Daisies and Science Fiction Theatre. I learned a lot from him. So I was ready by the time Killer Klowns came to do something with all these tools of the trade that I had learned up until that point.

DC: It’s a very electronic score, which helps convey that otherworldly vibe. When it came to instrumentation choices, was that dictated by budget or sound? A little bit of both? What made you lean so heavily into electronics?

JM: That’s a very good question, and the answer I have for you is this: I wanted to do it with an orchestra. And they were very cautious. They said, “We don’t want it to sound like any of the other horror movies that are out (which all have a medium-sized orchestra with a synthesizer on it). You’ve got to find a way to make yours sound really different. We like the fact that you’re classically oriented. If you can bring that to the table, but yet, have it sound interesting.”

So basically, there was one synthesizer that I really liked programming called the Yamaha DX7. It was a programmable frequency modulation FM synthesizer. Anytime you program a sound in it, and you recall it, it’s exactly the same. With pure analog synths, they’re absolutely wonderful, but sometimes they drift as they head up and cool down. It’s not that they’re bad to use. But once you come up with a sound and you like it, you have to record it immediately because it might sound different. Not drastically different, but the character might shift a bit.

I spent probably a good week coming up with sounds like tweaky popcorny sounds. Very ominous sounds and everything that would express the movie sonically. At the same time, I was coming up with musical material to use as well.

The very first thing we recorded was when the farmer came up to the spaceship in the forest. That set the sound when we recorded it with the engineer. We spent more time on that one scene to adjust the outboard gear so we’d have consistency. There were two engineers. One of them was an ace technician, the other an ace recording engineer. They had all kinds of creative input as far as making things sound really interesting. We used a very popular sampler at the time, actually two popular samplers. One was called the Kurzweil 250, and the other one was a Fairlight. Basically, a computer that made music. It was fascinating to work with.

DC: Let’s discuss the fantastic theme song by The Dickies. I’ve read that it was completed before the film, but had you heard it before you started working on the score?

JM: It was the night of the first screening. I’m pretty sure they had it locked into the movie already. It’s like the Ghostbusters theme. It was not used in the score, and the score had its own groove to it. I was comfortable doing that because their song is really awesome, and it works on its own.

It also bookends the movie, so you get the vibe that it’s a fun movie. It’s not taking itself too seriously. It’s not trying to be super gross and scary. That’s why we have fans that are as young as three or four years old because they’re allowed to watch it. Even though it may be scary at first, they think it’s fun!

DC: Since then, you’ve regularly partnered with The Dickies to perform with them. When did you first connect with them outside the film and decide to team up on these performances?

JM: I think it was the 25th anniversary of Killer Klowns, so 2013. I got a random call from someone who worked at the Chiodo Brothers office, and they described what is known as Monsterpalooza. I had no idea what she was talking about. She said, “We’re having a reunion!” and I thought they were going to have a barbecue at their studio or something.

[Laughs]

JM: So, at that convention is where I met the fans. And it was the first time they met me. I realized, “Wow. I think they deserve more than just visiting people at the table.” And then they told me, “Oh, The Dickies are going to play tonight.” That was the first time I met them in person. So then I thought, “How cool would it be to do a live-to-film performance!?” It wasn’t easy, but I got all the moving parts together to be able to put on a concert. So we got that together, and I’m happy to report that it’s gaining momentum! You may be hearing something about that in the next year.

Then I thought, I have to have a backup. So I thought of this cosplay rave party where I basically take the music, record it, and have it played the way I want to hear it with a different dance groove where people can dance and enjoy themselves. I was very inspired by the Scare Zone in Orlando, Florida. It is supposed to be a transition point between different attractions, but it became a destination. I’m looking at all this, and I’m saying, “It’s a giant nonstop party! Why isn’t this being repeated all the time?” So that’s basically what this is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be a place where people can cosplay and have a fun time together without any limitations on what they can do.

There’s also the video game, which I’m still working on and is a lot of fun. That’s got a lot of new music in it. It has realizations of music from the movie, but I treated it much differently. I told the game publishers, “I want to take it next gen. I think we have an opportunity here to bring it into today.” I’m working with Illfonic, and it’s lovely because their founder and their chief sound and music director come from music and record production backgrounds. They understand me getting obsessed over details and making sure things are a certain wait. I feel that when I turn tracks over to them, they’re in very good hands.

DC: You and The Dickies recently celebrated the Killer Klowns’ 35th anniversary with a blow-out performance show in Los Angeles. Did you ever imagine you’d still talk about and perform this music 35 years later?

JM: Well, if you had asked me this in 1992, I would have thought Killer Klowns was lost to the ether, even though it was one of my favorite projects to work on. I can tell you that my professional community, friends, and people in general would say, “What’s your favorite thing you worked on?” And I would tell them, “Well, one of them was Killer Klowns from Outer Space,” and they would roll their eyes in their head.

When I delivered the master tapes, I had a dolly with all the two-channel tapes, the big reels that had to be run on a big machine with like, an eight-and-a-half horsepower electric motor on it. It was serious analog stuff. So, we had 10 or 12 two-inch reels on a big dolly and I was in the elevator with some guys with suits on. They were probably accountants. And they said, “What is that?” So I said, “Oh, it’s one of your latest products, Killer Klowns from Outer Space.” They said, “Oh man, you can just dump that. That whole movie was a big effing waste of time.” And I said to him, “Well, you know what? This movie is not for you. There are going to be people that like this movie.”

And you know, I went to school with Christopher Young, who did Hellraiser, and I go, “You are so damn lucky that your movie was in theaters for weeks.” Same thing with Harry Manfredini and all those guys. “You’re so lucky. Mine took 35 years for people to really recognize it and for it to become a part of American horror genre culture.”

But you know what, I’m here, and I’ve always been here, and I was always here for Killer Klowns. And the fans, oh my goodness. If it wasn’t for the fans, all kinds of generations keeping this movie alive all this time, I wouldn’t be able to keep creating more music for them. That’s the best. Killer Klowns fans have a certain personality, which is they’re wonderful people. If you like Killer Klowns, that means you’re a very creative person. That’s what I think resonates; there is a subtext of creativity, originality, and imagination. It’s really wonderful.

DC: Final question: do you have a favorite Klown?

JM: So, that’s an unfair question. [Laughs] It’s like saying, which of your family members do you like the most? I love them all, but who do I have a close affection for? Well, there’s two, actually. There’s Shorty because I think Shorty represents the person in all of us who just gets sick and tired of being pushed around, and you just got to push back.

The other klown I’m absolutely fascinated with is Klownzilla because it’s like a higher-level evolution from klowns, like he’s part dinosaur and something else. I’m fascinated with him because he’s a mystery.

Keep up with John Massari and future Killer Klowns from Outer Space content by following him on X, Instagram, and Facebook. Additionally, you can purchase a vinyl copy of Massari’s Killer Klowns score via Waxwork Records.

Categorized:Interviews