Composer Julian Scherle on His Tech-Fueled Score for ‘Missing’

When director and co-writer Aneesh Chaganty’s screenlife thriller Searching first premiered at Sundance in 2018, the excitement surrounding the film was palpable. Quickly snagged by Sony Pictures, it received a wide theatrical release and soon became a genuine box office sensation. Made for less than a million dollars, the film would ultimately go on to make a staggering worldwide gross of over $75 million. Understandably, many were watching to see where Searching’s surprising success would lead. The film’s legacy now continues with Missing, a spiritual sequel to the original.

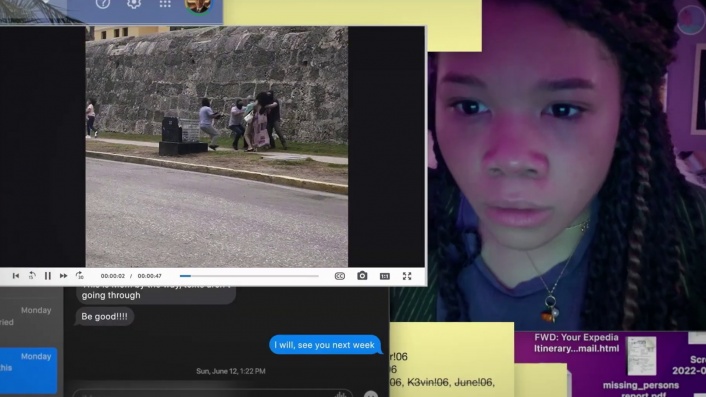

Missing stars Storm Reid (Euphoria) as June, a teenager who lives with her mom (Nia Long) in California. When her mom doesn’t return from vacationing in Colombia with her new boyfriend (Ken Leung), June reports her as missing. Unwilling to sit back and do nothing, June uses the technological resources available to uncover as much information as possible. However, what she finds takes her down a path she never expected.

Centering a teenager as the film’s main protagonist opened up a wealth of narrative and technological opportunities for the filmmakers. Technology and app capability have developed exponentially in the five years since Searching’s release, something a teenager would be familiar with and proficient at utilizing. Not only did this fact allow the filmmakers to display their creative use of screens to maximum potential, but it also opened the door for other parts of the film to do so as well.

One such collaborator on the film to do so was composer Julian Scherle. Continuously motivated by the creative possibilities that naturally reside within music, Scherle has long pushed the boundaries of what music can do and be. Whether releasing solo albums, scoring shorts, or collaborating with fellow composer Mac Quayle on projects like Mr. Robot, American Horror Story, or Scream Queens, Scherle’s thoughtful and innovative musical processes have elevated everything he touches.

With Missing, Scherle delivers a score as intricate and surprising as the film itself. Expertly grounded with emotional themes and potent instrumentation, the score’s heartfelt core becomes juxtaposed with swirls of electronic atmosphere, pulsing digital motivators, and artistically crafted sound design elements. Experimental in style, execution, and creation, Scherle’s bold and technical approach injects youthful, modern, and thrilling energy into each and every frame.

Dread Central recently spoke with Scherle, where we hacked into his process and approach to scoring Missing, his fascinating background, and so much more.

Dread Central: The roads that lead folks to film composing are always fascinating, as no two journeys are alike. Tell us a little bit about yours.

Julian Scherle: I grew up in the south of Germany in a super tiny village with a lot of nature and a lot of quiet. It was also very conservative [in] that area. My parents both surrounded me with music. My dad is a guitar and lute builder, so he had a workshop at the house. We also had a piano at the house; there was just always music. My earliest childhood memories are of me just hammering on a piano.

There’s always music around me, and I think a lot in music. I’m very sensitive to sound and very sensitive to my environment. And I had this epiphany when I was eight or nine years old. I watched The Fifth Element by Luc Besson, and I listened to [Éric] Serra’s score, and it was just freaking amazing. Getting that experience where you can disappear into this fantastic world that is just sound. Then, also having the realization that you can be that person. You can create that world that allows you to escape from reality into that world.

And I recorded it on a little tape recorder, went to my piano teacher, and was like, “I want to do this.” And she was like, “Yeah, I don’t know. It’s just a bunch of weird sounds, and there’s no piano in there. Sorry.” [Laughs] So that was my first really aware moment that there was something that’s called film music, and I could do this.

Then I studied music at a music school, a conservatory in Düsseldorf. As soon as I was able to, I basically moved away from the area that I grew up in. It was a dual study conservatory where you would learn the classical stuff and music analysis, but then it was also a technical school. So I also do have an engineering degree in audio engineering. I had to do some pretty complicated shit, and I’ve already forgotten everything, but I did a lot of math. I also did some programming and, basically, everything that’s related to electronics I had to do. So it was a very organized, scientific approach.

I think that sums up a lot of how I approach making sound. I like this improvisational aspect of jazz music and punk where you look at it more from the perspective of, “What can I do with this? How can I reinvent this?” Or, “How can I destroy this and rebuild it from scratch?”And then also the scientific aspect of a very organized work approach.

At some point towards the end of my studies, I got a little restless again and was ready to move somewhere else. It was either going to Nepal to work there as a music teacher for a while or going to LA and doing a film music internship. I flipped a coin, and it was LA. Then I got here, paid my dues, started out as an intern at a studio, and worked my way up to studio assistant. At some point, I started doing some additional music and started scoring my own projects; small indies and short movies. I also worked with Mac Quayle for a number of years on Mr. Robot and a bunch of TV shows which was really cool. And now Missing is my first studio feature!

DC: What a fabulous first feature to be involved with! How did you actually get brought on to this project?

JS: I worked with Natalie Qasabian, who is one of the producers. It’s Aneesh [Chaganty], Sev [Ohanian], and Natalie; they’re the three producers and also creators of the first movie, Searching. I worked with Natalie years and years ago on a short movie, so we knew each other, and we always were looking for some other opportunity to work [together] again. She’s fantastic. Super lovely and also a great producer.

And the two directors, Nick [Johnson] and Will [Merrick] came across one of my aliases. I do film scores, but I also just do music on my own and release that under different pseudonyms. It’s just a fun thing I do. I kind of create different aspects of my personality, create artists for those and release music under those artists. One of them is Són, and I released this weird concept album with like, 35 minutes of music. Somehow they found it, loved it, and used it while they were writing the script for Missing.

At some point, they were talking to the producers about what kind of composer could come on board for this, and they were like, “We should figure out who that guy is and contact him.” Then they found out it was me, and Natalie was like, “Oh! I know this guy!” It really felt like a supernatural fit. As people, but also creatively. It was just a perfect, perfect fit.

DC: Searching and Missing are well-known for utilizing screens heavily and creatively. How did that impact your initial approach to the score? Did that inspire you in any particular way?

JS: We wanted to create something that feels very connected to the feeling of seeing everything right in front of you. Something that’s very claustrophobic and very close. We really wanted it to feel almost like we’re inside June and experiencing what she’s experiencing.

For me, the most fascinating aspect was, “What is the human-machine interaction? What kind of communication gets lost on the way?” You know, compared to if we talk in person. Even right now, we’re both looking at each other [via Zoom], but we are not really looking into each other’s eyes. We’re humans, and we adapt to these different types of communication, but there are still aspects that are getting lost on the way. That was the initial question that we basically asked, and how we could translate that into music.

So one aspect that I was exploring was compression. I was very curious to see if there [were] any studies out there that [were] dealing with that. I found one study that was basically looking at non-musicians that don’t have a trained ear, and they would listen to orchestral music uncompressed and then a compressed version. And the result was that the more compression you introduce, the more anxiety-inducing the signal becomes. It was very interesting.

So I was thinking, “Ok. What happens if I don’t compress something just one time? What happens if I recompress this thousands and thousands of times with a really low compression quality?” Basically, it created this kind of compression artifact soup that is beyond recognition. And I did that with all kinds of different source signals. I’d then listen to all of this and try to evaluate, “What does it do emotionally, and how can I use it?”

Another aspect was that I was always interested in including AI in the composing process. I found this cool open-source platform by Alphabet, where you can resynthesize audio signals. You can also train your own algorithms so you can create your own module, which was very time-consuming and very unstable. Their server would just crash constantly, or [there would be] some errors in their code.

But that was also a huge field of just fun exploration. It was, “Let me take some of these compression artifacts, train a system with that and then feed Storm’s dialogue from set into it and see what comes out.” It was another aspect of how to include the digital dirt that is created.

And then the third thing that I included quite a lot in the score is a specific type of microphone that doesn’t record audio. Like, not waveform pressure. It records electrical interference. Any type of digital device that you have, or any electronic device that you have, has a circuit board inside. And that circuit board is constantly radiating different voltage changes or capacitor that charges or loses charge. It creates all these different textures and rhythmical elements, and this microphone can record that.

You can record your screen, for instance. And depending on where you point it, you hear different stuff. So I recorded a huge amount of that stuff. Then I went through it, cherry-picked what sounded interesting to me, and reapplied the first two ideas I had; compression and resynthesis. That’s the foundation for all the electronic elements that you hear in the score. All the textures, drones, all those bigger swells, and that digital gritty stuff.

From there, we also wanted to create this big contrast to this really digital, claustrophobic sound world and create something that’s very organic, warm, cozy, and very relatable. That’s the family aspect that is the heart of the movie, the core of the story. That’s all upright piano that’s close mic’d. I still wanted to get this really intimate, kind of claustrophobic sound. And then, there’s no way of beating what strings can do. So we did record a bunch of strings in Budapest. Those are the two sound worlds, the two poles that we created.

DC: Those emotional moments are really effective, and the music feels very intimately tied to June’s story. What was the process like for achieving that cohesiveness?

JS: I did write a lot of themes, and I wrote very early before anything was edited. I wrote that during the script phase and was already in contact with the director, sending it back and forth. We were testing it in different ways, with different instrumentation, and different tempi, and were already talking about, “Oh! This could work really well for that area of the movie.” Or, “This could really work well here.” So by the time they got into the edit, they already had a huge amount of music that they could play with.

We also never had any temp music. I really enjoy that kind of workflow. I would always just give over stems and everything to the editors. They would edit the music along with the picture, and then at some point, I would take it back and keep working on it if we needed new elements. That workflow really allows the score and the edit to grow and change at the same time. It was a really close collaboration between the directors, the editors, and me.

DC: This movie has a great flow and pace. Did that close collaboration also benefit you there?

JS: That was a huge trial and error process where you really just have to test. Since we did have music in the work so early on, we could really look at, “Ok. We just watched the whole movie, and we came out with this feeling.” Or, “We didn’t feel like this moment was really hitting exactly how we needed.”

Then, you can find and calibrate all those different parameters. Do we want to have more of a drive in this sequence? Lead the audience in this direction? Or do we want to slow it down in certain ways? We can create those different moments and breathers. That’s a huge, huge part of realizing the directors’ and the producer’s vision of how they want to structure the movie. Because we did have the music in already, we could really fine-tune all those parameters.

DC: Not only did you have the screen aspect to contend with, but also all the electronic sounds that come with various devices, apps, and programs. How did you navigate that?

JS: I kind of found my way back to film through sound design. For a long time period, I was turned off by film music because it felt [like] a lot of cliches that are just reused and very obvious manipulation of the audience. And then, I started doing sound design for student films when I was still studying.

At some point, I realized that you can really subtly manipulate the audience and guide the audience through sound design. And, as soon as some sound creates some type of emotion, I defined that as music. For Missing, that was really the perfect project to use it that way, where you very subtly guide the audience.

It is also such a micro-timed score. You’ll have this little movement of the mouse pointer over a picture, and then June has an idea, and then she moves over there. That ten-second sequence has to be fully scored to mirror exactly what she’s going through. And you can do that very, very effectively with that type of sound design score.

There’s also just the overall feel as there’s no layer between you and the sound, creating this claustrophobic feeling within the theater. Or, depending on where you go, it might be a huge theater that you see this, but you’re so close visually. But sound-wise, you’re so close to what happens. So that was a really fun process to explore.

John Chapman, he did the surround mix, and we were playing a lot with, “Ok. Where do we place those things in our surround field?” And, “How do we evoke certain feelings?” By having that stuff swirl around you and come from all kinds of different directions, it is like the feeling of fully losing control. I really wanted it to have this type of feeling of adrenaline rushing through your body where you feel it start at some point of your body and just go through all your limbs. This kind of wave. I also use that wave movement that basically goes like a literal wave through the theater, washing over the audience.

There’s a lot of stuff that we played with and, again, trial and error. We saw what worked and what didn’t work. Sometimes it doesn’t really do what was intended, so we’d try something else. It’s just having some ideas and not being shy about trying those ideas. Oftentimes, even if that specific idea doesn’t really do what is intended, it might lead to another idea. I’m just very glad to have worked with filmmakers that are working in a very similar way where if there’s an idea, it is going to be tried. No matter what the idea is, it can always create some other impulse and some other idea.

DC: You’ve mentioned the idea of trial and error a few times, and knowing when something isn’t working, can be difficult for some folks. Has that ability and willingness to “kill your darlings” been something you’ve had to learn over the years? Any advice for those that may struggle with that?

JS: First and foremost, don’t take any of those things personal. Nothing is personal and nobody is attacking you. If something doesn’t work in the context of the film, then it doesn’t work. And ultimately, find filmmakers that you align with creatively. You will then minimize those types of moments. Of course, there’s always moments where there’s creative disagreement. It’s just natural. Everyone has their own creative sensibilities and different tastes.

You also have to be really aware that you are a part of this movie. You’re not the movie. It’s not your score. You’re writing the best possible score you can for the movie. For me, it was never really an issue. But I know, especially people that are just starting out, they can get protective of their work. Just remind yourself, it’s not personal. It’s not critiquing your music per se. It might be the most beautiful piece ever written by a human. But if it doesn’t work in the content of the movie, then it doesn’t serve. If it doesn’t serve the story and the movie, then it’s not the right piece of music.

Missing is currently playing in theaters nationwide. In addition, Scherle’s score for the film is now available to stream on all major streaming platforms via Milan Records.

Categorized:Interviews News