The Rambunctious Queerness of John Waters’ ‘Multiple Maniacs’

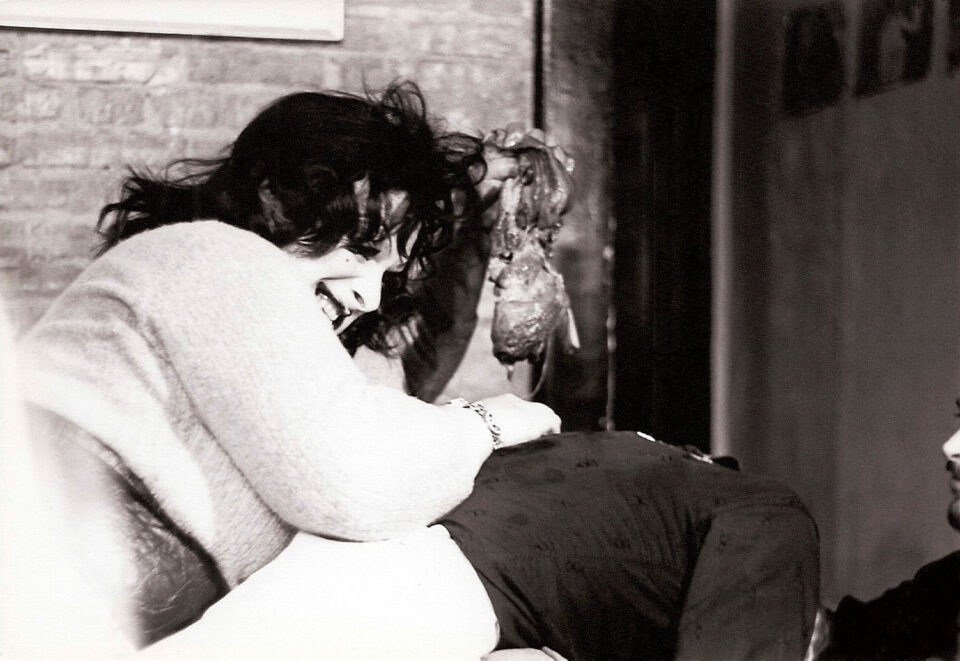

In the realm of confrontational cinema, John Waters and the rest of the Dreamlanders (a core group of performers named for his production company) were all shiny steel blades sharpening each other’s talent for tastelessness. You would be hard-pressed to see a more loathsome and disturbing collection of weirdos eating dog shit, prolapsing their own anuses on demand, and killing authority figures without the slightest hint of remorse. Thankfully, the Dreamlanders are not the only cinematic extremists in history. But their films are precise in their assessment of what it means to be a queer “American” and all the nasty baggage that comes with every syllable. Hot off a string of 8mm short films, and the feature-length Mondo Trasho, Multiple Maniacs was the project that truly unleashed John Waters and the Dreamlanders onto an unsuspecting public. Taboos weren’t just broken. They were gagged, stabbed and stuffed in the back of a trunk waiting to be driven right into the ocean. It’s easy to take for granted how much of the disgusting body humor has been normalized since its release, yet Multiple Maniacs is as relevant today as it was in 1970. With the popular discourse on social mores being shaped by hyper-sensitive and pathetically repressed right-wingers, Waters’ films are an oasis of filth in the face of fascist intimidation.

The story of the film follows an exasperated Lady Divine who wants to disband her traveling troupe of criminals, known as The Cavalcade of Perversion. She wants to pursue a greater purpose after a life of thieving, whoring, and murdering has left her bereft in a broken relationship. Not willing to sacrifice his bread and butter, Divine’s partner Mr. David (David Lochary), plots to kill her with the help of his lover Bonnie (Mary Vivian Pearce). After a religious experience leaves Divine rejuvenated, she and her new lesbian lover Mink (Stole) devise a plan to murder David and Bonnie, thus freeing her from a cycle of abuse. This plan is thwarted by Bonnie’s itchy trigger finger, which executes Divine’s daughter Cookie (Mueller) and her boyfriend Ricky (Morrow), leaving the fabulous gang leader without much of a reason to live. After gruesomely murdering everyone left alive in a dramatic episode, Divine finds herself lonelier than when the film began. She is promptly raped by a giant lobster named Lobstora and becomes a monster herself: spilling her rampage all over the quiet streets of Baltimore before being gunned down by the National Guard.

In her essay “Genuine Trash,” author Linda Yablonsky notes that Multiple Maniacs turn villains into heroes by “extolling the underside of human nature.” Horror films, and the realm of the genre as a whole, allow artists to challenge models of behavior that are considered virtuous to a straight society. Slashers, monster movies, ghost stories, etc all share one common thread in that their respective boogeyman makes a mockery of the peace we think exists when we turn a blind eye to true atrocities. In the US, horror as a genre was gutted and skinned by filmmakers who sought to zap audiences from their comfort zones and get them to think critically about how televised warfare (both domestically and internationally) was being utilized as a tool for grooming a complacent public. If you were white and living in the city, you could pack up and move to the suburbs to avoid the reigning terrors of the government you put into power. Once there, you might rest easier knowing that your children were safe from the consequences of your own generation’s sins. But not if Krug and Company have anything to say about it.

Multiple Maniacs, despite being too comedic to be truly scary, follows a similar logic to the gnarly grindhouse staples that would shape the coming decade in that it puts the focus entirely on the villain. The Cavalcade of Perversion, who maim and steal from the Baltimore elite, are given complex interiors and motivations beyond evil for evil’s sake. The parallels between Waters’ film and Wes Craven’s The Last House On The Left are uncanny. Both men draw on the perverse religiosity of Swedish director Ingmar Bergman to shape their wicked worlds, and one doesn’t have to squint too hard to picture the band of psychos in Craven’s film being chummy with the Cavalcade. Divine and Krug Stillo (played by David Hess) even share a warped family life that is essentially a walking parody of the folks they set out to traumatize. Both she and Krug, at different points in their journey, must perform the roles of upstanding citizens complete with ill-fitting clothes and attitudes. This does not last long for either of them. And each of their respective films make a point in delineating how alienated from reality their protagonists really are. The bell rolls for Krug in brutal fashion, rightfully so, and at the expense of a nuclear family’s sanity. Divine, on the other hand, is empowered by her ability to act as a mirror to the rest of society. In Multiple Maniacs, drag is a weapon.

Clowning the straight world by way of drag is a true American tradition regardless of hard genre classification. Take for example, the Gay Girls Riding Club and a film like What Really Happened to Baby Jane?, directed by GGRC founder Ray Harrison. What Really Happened to Baby Jane?, as its title clearly spells out, is a drag parody of Robert Aldrich’s 1962 classic starring Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. The 30-minute short goes pound for pound with the original concept, even going so far as to lampoon the infamous Oscars slight against Davis back in 1963. Thomas Casey’s Sometime’s Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things from 1971 rides the same cultural vibrations as the films discussed above, yet is significantly more bitter. The story of two thieves on the lam living out a domestic fantasy, with one man acting as a jealous housewife, entices the viewer into a honeymoon state ala Douglas Sirk, only to end in a violent tragedy by way of Nicholas Ray. Of course, I would be remiss not to mention Psycho and the knowing, audience-prodding characterization of Norman Bates, but that’s a story for another time. Divine, the performer is a descendant and antecedent to these characters and others throughout cinematic history, and Multiple Maniacs is his debutante ball. He’s been (allegedly) arrested during the production of Mondo Trasho, but her actions in this film put him over as the reigning Queen of Filth once and for all. I find Divine as powerful a figure of his own time as Godzilla was in the atomic age. Multiple Maniacs extol her evil deeds and practically elevates her to sainthood. She is a beacon of light that shines on the toxicity against queers of all sizes and shapes. A toxicity that is dealt back ten fold and in broad daylight during the film’s infamous climax.

Divine, the character, is a deeply conflicted woman. Her faith is tested by a loveless heterosexual relationship and growing dissent among the Cavalcade. When she is assaulted by two members, she seeks penance in a church and is even accompanied by the Infant of Prague (played by a visibly uncomfortable non-actor in a silly costume). Once at church, she is struck by biblical images of Christ feeding the multitude and the stations he passes en route to his execution by the state. Having committed a murder that morning and escaping, revolver plainly in hand, in a stolen Coupe de Ville is only two acts of transgression for which she looks to be absolved. But as the scene goes on, and a curious Mink edges closer to her in a pew, Divine realizes that filth and perversion are her crosses to bear. That if the state can continue to beat do-gooders in the streets relentlessly, their codes have no legitimacy. Crimes are the only way to live free, and there is no pleasure too shameful to indulge in, including the usage of a rosary in anal play. Mink and Divine consummate this newfound freedom in a glorious sequence known as the “rosary job” and set to a folksy rendition of “He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands”. The scene apparently brought the pastor of the church where it was shot to tears. It disgusted a US censorship board who were powerless to stop the film from coming out. And without question, this scene must’ve influenced the Canadian distribution company, with whom Waters tried to establish a business relationship, to burn the print they received. They hate Divine because she lived her truth in spite of the horrors around her. Losing her few remaining tethers to society in a combination shoot-out/cannibalistic evisceration would be enough to drive anyone insane. Divine came home to tragedy and responded in kind.

Sharp viewers will draw comparisons between Divine’s rampage in the finale of Multiple Maniacs and the equally disruptive antics of the Jackass crew. Waters himself has co-signed the gross-out variety prank show, even appearing in Jackass Number Two. It is inspiring to watch Divine wreak havoc on Baltimore suburbanites to “Mars, the Bringer of War”, a movement in Gustav Holst’s seminal opera The Planets. The kind of free-flowing anarchy on display in this scene is found in abundance on the Jackass tv show and its many spin-offs. Both of these projects offer a queer catharsis, where the appropriate response to the cage of suburbia and the policies enacted elsewhere on its behalf are met with a terroristic sledgehammer. As Veronica Phillips notes in her piece on both subjects: “Like Waters’s body of work, the Jackass films hum with a sense of destruction within suburbia. Your own backyard can be a space to push your sadomasochistic limits.” For the Jackass boys, confronting their own mortality has led to some of the most poignant moments in the series, with Jackass Forever acting as a testament to a lifetime of debauchery and disruption that has been a crucial part of American culture. The end of Multiple Maniacs, in all its fervor, paints a sobering picture of militant queer hatred. Waters has an incredible sense of humor and is a more romantic filmmaker than he is given credit for. But just as well, he is an expert political commentator. Divine being gunned down in broad daylight is entirely a reaction to the turbulence of the late 1960s. It is an abrupt end to a film that had thus far been a wild ride. Waters punctuates this story with a hell of an exclamation point, no doubt to show what a coordinated effort of hatred has in store for vulnerable communities. But most importantly, to give misfit queers an icon to aspire to. I would rather be like Divine than some kind of focus-tested version of what a multi-billion dollar conglomerate thinks a queer should be. Monstrous and dangerous. And with enough of us roaming the streets to crush the opposition.

Waters approached this film with the explicit goal of making the most offensive thing on the market. His philosophy of making “exploitation films for art houses” greatly informs the methods to his madness. Influenced by European sex films and the glorious splatter of H.G. Lewis, Waters found his voice and belted out the dirtiest tunes he could phrase. But sleaze is only half the charm of Multiple Maniacs. Outsider cinema is most powerful when it offers an unambiguously sympathetic perspective on people considered to be the dregs of society, and the film balances its transgressions with genuine consideration for Divine and her domestic strife. Multiple Maniacs is queer in every sense of the word, and Waters incisively taps into the struggles of being openly queer in a hostile environment. Divine is a proud criminal, and her longing for a better life is relatable to anyone whose life is organized purely around survival. A film like this goes a long way to show that in a politically violent milieu, the people best suited to document marginalized communities are the communities themselves. This film might have rough edges, but Waters is able to have his cake and eat it too. Nothing in the mainstream could have ever produced something as raw as what the Dreamlanders concocted. And we, as an intelligent viewing public, should always be wary of any attempts at a compromise for mere exposure. It’s artists like these who have paved the way for us to be our true selves in cinema, and the very least we can do is keep that filthy flame alive.

Categorized:Editorials News