The Perspective of Horror: Atmospheric Use of the Camera

In games, this task is given to the camera. How the camera is implemented can make or break our immersion. In a very literal way, define how we view the world.

I had forgone the walkie-talkie to make room for more chattering teeth and plastic fish. As soon as I entered the facility through the fire exit, a glint of warm light highlighted the crack in my face shield. I saw it: the apparatus. All that separated me from its radioactive embrace was a long, dark hallway, broken at its sides by more dark hallways.

The spider that killed me came from the right.

The door to my left was locked and was now covered in blood. While dead, I watched my fellow company assets from the third-person perspective as they followed in my footsteps. Dodging the spider and ingloriously running over my cocooned corpse. With control of the camera, I was able to see the Coil-Head that awaited them. But their limited field of view meant that I soon had a new friend in the death chat.

Camera placement is important, and so are the perimeters of the lens. Lethal Company routinely produces cheek-tightening jump scares because of the narrow field of view (FOV). It’s forced tunnel vision, and it’s a choice that separates the game from faster-paced FPS games.

Putting the FOV on a slider—where the higher the number, the wider the view—Lethal Company’s FOV is only in the 60s, while standard shooters default around 80. Further, small graphic additions, like the outline of your mask, can hide monsters that sit close to the floor or hang above doorways. This often leads to death, and it’s what keeps the game exciting.

We humans have a long, complicated history with the way we like to frame things. The earliest writings on cameras go back to Chinese philosophers in 400 BC. Then, like now, we use them to reflect on the nature of sight. Even small alterations to a camera can make for entirely new experiences.

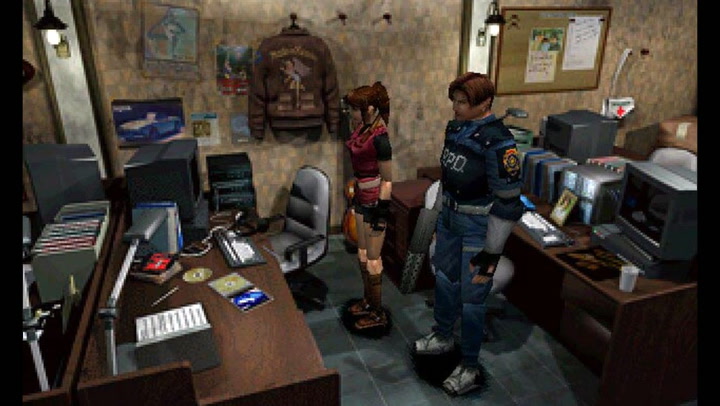

Nearly 30 years on, and the original Resident Evil still works.

The fixed camera and odd controls may have been, in part, technical limitations of the time. But they also served as a dial to the tension. Having to reorient every time Jill or Chris entered a room left the player feeling unsure they could change direction in time. Should a dog jump through a window or a zombie shuffle around a corner? It gave the impression that in this world, even Raccoon City’s finest were literally scared stiff.

No matter how many bullets and herbs you had stuffed in your pockets, the camera was a constant assurance that the mansion was watching and was in control. It was a trick that worked for the next few Resident Evil entries. It spawned a slew of games with similar schemes that ranged from the excellent Fear Effect and Dino Crisis to the head-scratchingly-odd Covert Ops: Nuclear Dawn.

By Resident Evil 4, things had changed.

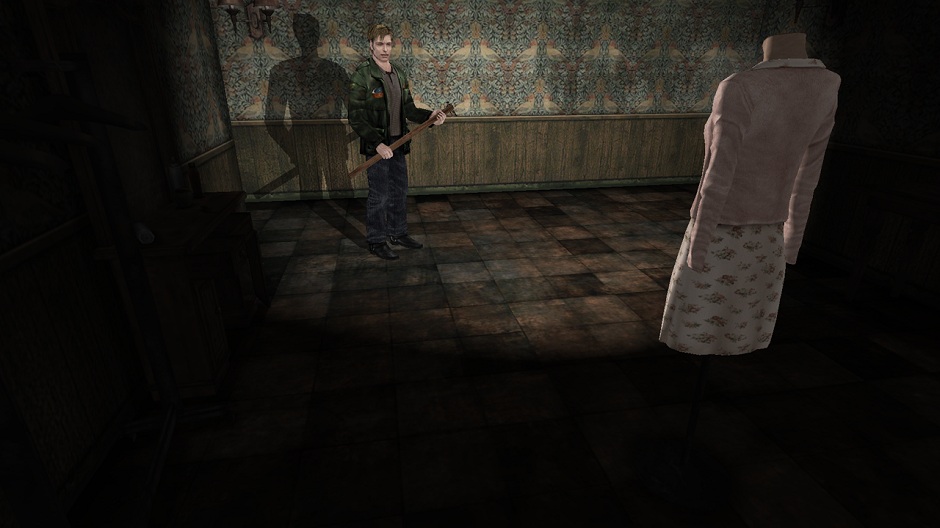

Fixed cameras had become routine for the era, and games like Silent Hill had proved that a looser camera could quicken the pace and open up new worlds of gameplay. But Capcom pushed it a bit too far. By keeping the camera behind Leon and zooming in for aimed shots. The player was now in control of the environment and could dictate the pace of combat.

It was a decision that made sense; Leon wasn’t a rookie anymore, and the camera changes reflected his increased agency. But it wasn’t really horror anymore, either. It’s hard to be afraid when roundhouse kicking entire mobs that you’ve baited into a choke point.

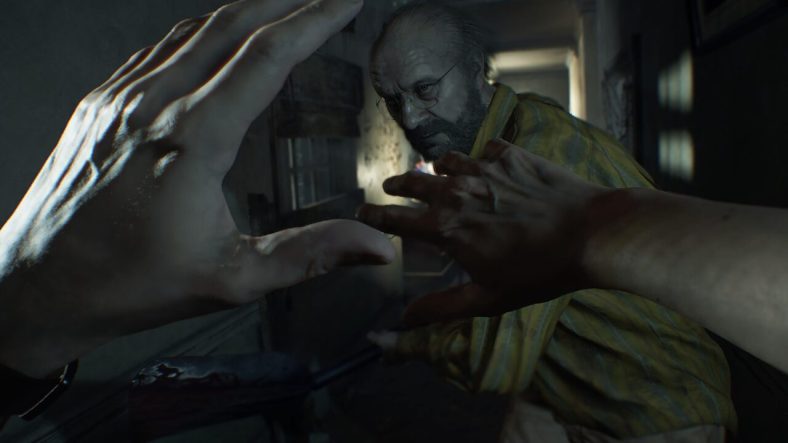

The more action-oriented setup would remain in place until Resident Evil 7. The camera was moved to the first person with a tight perspective and darkened areas around the edge to narrow the frame. This is an effect called a vignette. The new camera, paired with the tight confines of the Baker house and more deliberate movement. It felt like a return to Resident Evil’s roots and made for one of the few entries that could unabashedly be defined as horror.

Resident Evil: Village saw the return of action orientation.

The FOV was now locked to 80, and the vignette had been reduced. In addition, there were now more open environments and abundant resources for the player to grab. They were minor changes that shifted the series back in the direction of action and fluidity.

Even now, as we strap peripherals to our bodies in new ways. It’s still the camera that takes charge of our immersion. With a world of new perspectives on the horizon, I have no doubt it will be the horror genre at the bleeding edge. Pushing us into the unfamiliar and reframing our escapism.

Claiming a game to be horror is a bold move; it promises not only a play style but also a feeling. The eyes may be the windows of the soul, but the camera is a porthole to someone else’s nightmare: place it with care.

Categorized:Editorials Horror Gaming