The Doll Lives On: Class and Consumerism in ‘Child’s Play’

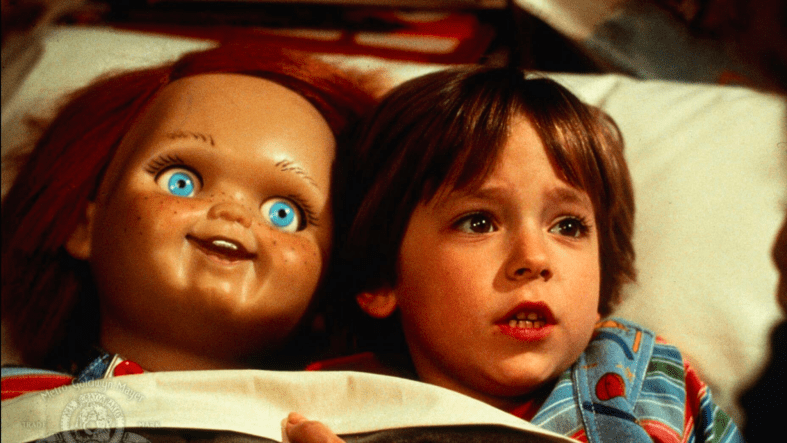

The doll has always been a mainstay of the horror genre from Dolls (1987, Stuart Gordon) to The Boy (2016, William Brent Bell). However, it would be impossible to argue that no other doll in horror cinema has become as etched into the collective consciousness as Chucky. A demonic creation brought to life on the screen by director Tom Holland (Fright Night, 1985) in the form of Child’s Play (1988), the cursing, knife-wielding blue-eyed doll was to become our ‘friend to the end’ for decades to come.

An undisputable icon of horror, Chucky has earned his place in the horror villain Hall of Fame forevermore. Even those who have never seen Child’s Play instantly recognize him (to quote my sister who falls into such a category), Chucky is “that doll that likes to stab things”. The chilling forebodingness of the film lies within the notion of a child’s beloved toy turning into a violent criminal but is further enhanced through the themes of mythology and magic. This is told through the character of Charles Lee Ray (Brad Dourif) whose mere name creates a sense of terror as it represents an amalgamation of three infamous killers: Charles Manson, Harvey Lee Oswald, and James Earl Ray.

Also Read: ‘Trick’ is a Delicious Halloween Treat [The Overlooked Motel]

Although on the surface it might appear to be a scary thrill ride peppered with dark humor, Child’s Play is not afraid to tackle some harrowingly disturbing subject matters as Holland takes a realistic and often uncomfortably close look at social inequality, sexual assault, and how institutions fail to protect those at risk. Set in the state of Chicago, the location is an integral component of a film that offers an unflinching portrait of poverty, crime, and suffering. The centerpiece of the action is the unforgettable Hitchcockian apartment now immortalized forever in the film’s promotional poster and of course by that scene.

Living amongst the tangibly gritty working-class streets against a backdrop of troubling economic struggle, Karen (played with tenderness and sincerity by Catherine Hicks) is a single mother doing her best to keep things afloat. When her son Andy’s (Alex Vincent) birthday arises, she uses her money shrewdly and sensibly to buy him the practical things he needs (a new pair of trousers and coat) rather than the Good Guys doll he so desperately desires.

Therefore, in addition to her challenge of ensuring food is on the table and Andy is provided for, she also must bear the pain that she’s not delivering her son the one thing he seeks above all else. She is (if only momentarily) a direct source of disappointment to him. During one of her shifts at the department store, the mother manages to successfully obtain the coveted doll from a backstreet seller and it’s at this point that the suspense begins to mount.

Also Read: I Once Disliked “Absentia.” Now I Love It.

We also learn that Karen has gone through a divorce, a process that can often leave subtle but very lasting marks on the child left in the middle. Armed with this knowledge from an early stage, the audience can quite easily be led into believing that Andy is unbalanced as a result of this trauma. In a rare interview, Hicks stated that “with the script came an in-depth backstory which explained that part of the reason why Andy isn’t believed is because he has been prone to trauma and fantasies in the past.”

Much of the tension and horror exists in the disbelief that circulates and transfers between the characters as to who is the killer. We too are teased with glimpses of an indiscriminate child darting across the hallway or a pair of children’s feet tottering about the apartment (either of which could belong to Andy or Chucky). Interestingly, in the original draft of the script, Andy was written definitively as the killer. But this idea was abandoned assumedly because it was deemed too unpalatable. However, for a small portion of the film, Holland successfully manages to keep first-time viewers guessing. After all, we don’t explicitly see Chucky take a knife to Karen’s friend Maggie (Dinah Manoff). Until the true nature of the demonic doll is revealed, Andy remains the number one suspect.

Also Read: Halloween 5’ Is A Slasher With Heart Thanks To Tina Williams

One of Child Play’s greatest achievements is its ability to balance horror and humor, most of which derives from Chucky behaving in unexpected ways for a toy doll. In both his actions and speech, Chucky is the subversion of a friendly, polite, and lifeless object merely comprised of wires and stuffing. In particular, his profane language (which undoubtedly helped garner its contentious reputation) is utilized for comic effect such as when he retorts “go fuck yourself” to the neighbors.

That is not to say that all the laughs stem from Chucky though. In fact, the first comes from child protagonist Andy who in the opening scene is preparing a breakfast for his mother to coax her out of bed on his birthday. With clumsiness and hurried excitement, the six-year-old drowns the (Good Guys) cereal in milk and slaps something close to a third of a tub of butter onto burnt toast. Unlike Chucky, who harvests laughs from the audience because he behaves against our expectations, here Andy’s actions are softly amusing for the opposite reason; we recognize his behavior as being ubiquitously childlike.

Also Read: The 8 Scariest Nuns In Horror History

Arguably Child Play’s central theme is its warning against the hostile and inhuman world of advertising. Writer Don Mancini explained that initially, he was aiming for the film to be a “dark, satire on the world of children’s marketing” and references an episode of The Twilight Zone entitled Living Doll (1963) as one of his strongest inspirations.

The episode features Talky Tina, a doll who embodies the resentment that its young owner Christie has for Erich, who has recently remarried her mother, Annabelle. As you can guess, all does not end well for poor Erich and the disbelieving Annabelle discovers the truth all too late. However, rather than leave us on an unnerving final note, we are provided with a comforting epilogue: “Of course, we all know dolls can’t really talk, and they certainly can’t commit murder.” By comparison, Child’s Play does not allow us off the hook so gently. In the final shot, Andy walks out the door looking tentatively behind him, he is not totally convinced that Chucky is dead. Through our empathy, we cannot help but share in this assumption of fear.

So far did Mancini wish to wield his views about consumerism that he also intended for the character of Karen to also be the Marketing Executive of the toy company to make the “satire of the world more pointed.” Despite this idea not making the final cut, the story behind Child’s Play and its legacy are rooted in consumerism with real life and film reflecting back at one another.

Also Read: Celebrating ‘Return of the Living Dead 3’

The evolution of Chucky derived from the ‘My Buddy Doll’, a product released in 1985 by Hasbro which came with a deftly manipulative advert and its own easy-to-remember jingle. In the 30-second piece of expertly exploitative marketing, it’s easy to see why Andy feels his life would not be complete without a Good Guys doll of his own.

The ad shows a smiling child running in and out of an expensive-looking faux Clubhouse, pulling a dog on a trailer, and climbing trees with the Good Guy doll at the center of it all as Chief Curator of Fun. In Holland’s film, Chucky is dressed in a similar style to My Buddy in a striped t-shirt and dungarees. He even has his own song played on repeat throughout the television ad claiming “Good Guys will be there for you, best friends till the end.” Not content with leaving the pitch at this, the voiceover is careful to remind the young audience to “tell Mum and Dad you want a Good Guy and don’t forget you can buy all our Good Guy accessories.”

Regrettably, (as in real life) it’s not only the children in Child’s Play who are victims of the marketing machine as we also see Karen cruelly exploited by consumerism through her job and oppressive boss who makes her work late on Andy’s birthday. Even this small detail acts as a commentary on consumerism. If Karen didn’t have to work longer in the name of profit, events might not have ended so tragically at the hands of the ‘must have’ toy.

Also Read: What Will Be John Carpenter’s Legacy: Films or Music?

Unfortunately, mother and son don’t stand a chance against the Good Guys brand; the cereal makes up part of Karen’s heartfully prepared but unappetizing-looking breakfast in bed delivered by Andy who in turn wears Good Guys pajamas whilst watching a Good Guys advert play on the television. The influence and control of its products are omnipresent and swallow everything up to such a suffocating point that escape seems an impossibility.

Mancini’s original script was titled Batteries Not Included but as Spielberg got there first with his 1987 film of the same name, the title was soon changed to Blood Buddy before its third and final title was agreed upon. It may not have the same panache as Child’s Play but in no scene would the original title have appeared more suitable than when Karen pulls away Chucky’s clothes and opens up his back to find that he has in fact been operating without the aid of batteries.

This precedes one of the film’s key moments whereby Chucky sheds his angelic façade and reveals his true nature to Karen when she threatens to throw him into the fire. It also marks a significant and unnerving change in her behavior toward Chucky as she stretches her arm shakily under the couch to grab him, now clearly full of fear to touch something that not long ago she saw as an inanimate object devoid of any threat.

Also Read: These Outrageous ‘Amityville’ Films Are Streaming Now

Surprisingly, both Hicks and Vincent report that they did not experience any feelings of terror towards the Chucky doll. Hicks even developed a technique whereby she substituted her fear of Chucky for her real phobia of snakes to bring authenticity to the performance. Holland has spoken of how the fear of toys is something that is deeply ingrained in us all from a young age, something I can personally attest to. I clearly recall being around the age of five or six and imagining my own dolls, action figures, and teddy bears coming to life, walking freely and unnaturally about my bedroom.

If we are honest with ourselves for a moment, we’d concede that at one time or another, we’ve all been led to believe our lives would be enriched by having a certain toy in our possession. As a child, I can remember seeing adverts at Christmas time and thinking “I’ve got to have that.” It’s hard (not to mention slightly unsettling) to explain just how desperate the urge feels.

The fictional world that the six-year-old Andy inhabits is constructed heavily on the power of advertising. How unsurprising, then, that it gives birth to such a destructive and narcissistic entity and how fitting that in the real world Child’s Play would go on to develop its own endless stream of merchandise in an ironic example of life mirroring art. As the film turns 35, it continues to hold up for its social relevance and for being uniquely comedic and entertaining. One thing is clear, Chucky remains an enduring if not slightly offbeat classic of the horror genre.

Categorized:Editorials