‘Orca’ Taught Us Long Ago Not to Mess With The Ocean

In Orca (1977), whale expert Rachel (Charlotte Rampling), states that Orcas can communicate millions of pieces of information through their sonar. Movies are like our own sonar, expressing complex emotions and messages. Director Michael Anderson’s film, however, can be summed up in one simple statement: Do not fuck with Orca whales. Based on the surge of encounters in which Orcas have been ramming boats, maybe it’s time we look back on a film undeserving of its ship-wrecked reputation.

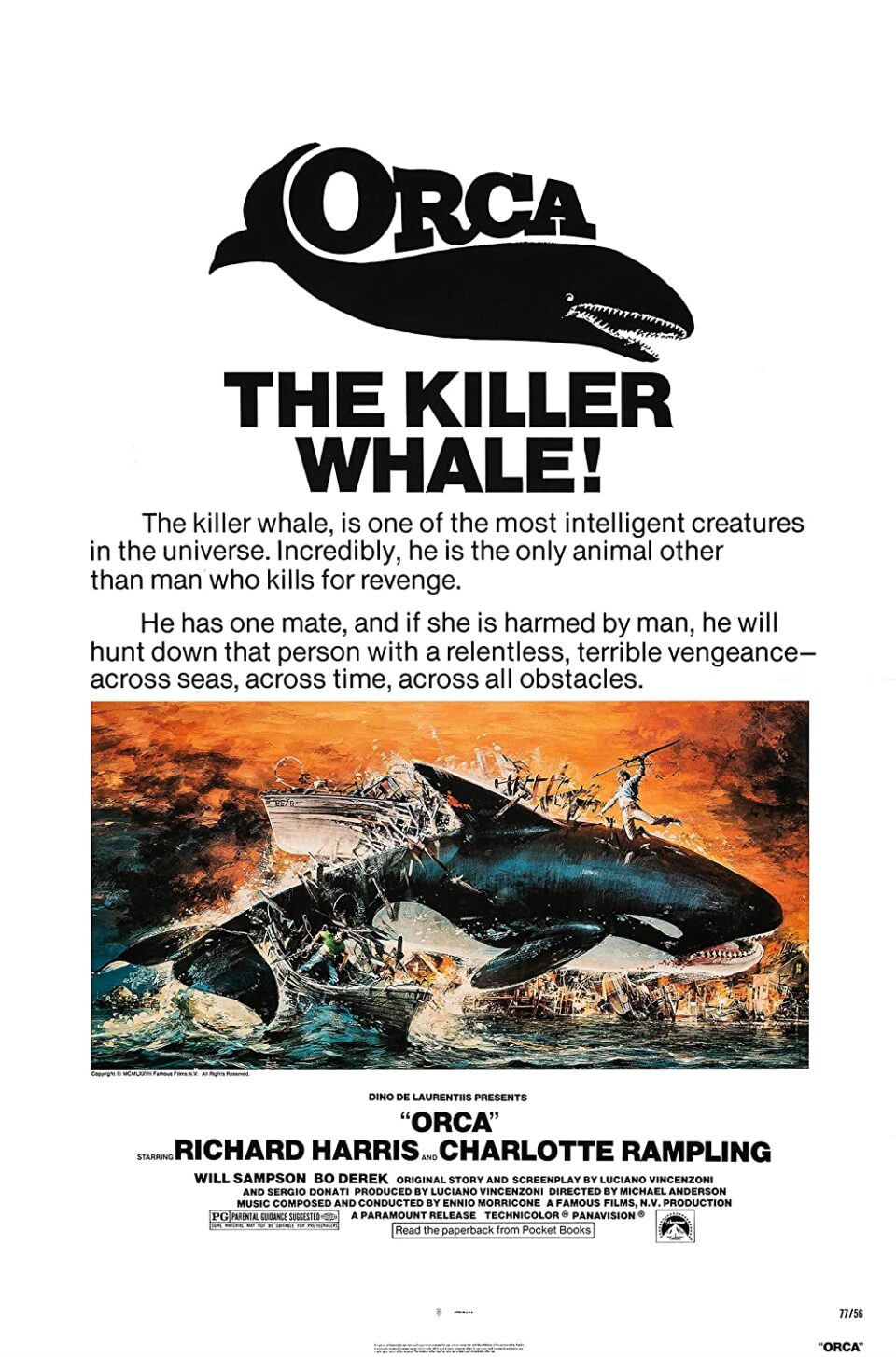

After Shamu became Seaworld’s exploited prisoner but before Willy was ever freed, legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis sought to capture the box-office appeal of Spielberg’s sharksploitation masterpiece, Jaws. He tasked screenwriters Luciano Vincenzoni and Sergio Donati to find the ocean’s most badass creature, one that could pulverize a Great White. They found just that in the Orca whale. In the resulting script, we meet Captain Nolan (Richard Harris), a fish-out-of-water Irishman stuck in America and trying to pay off the mortgage on his boat. When he witnesses an Orca demolish a Great White—Dino’s way of saying my whale is scarier than your shark, Mr. Spielberg—Nolan gets the idea to capture one alive. What follows is a terrible accident that leaves an Orca female and her baby dead, and an enraged male hell-bent on vengeance.

Orca didn’t necessarily belly-flop at the box office, but it wasn’t the huge splash that it deserved to be, either, making roughly $14 million on a budget of $6 million. Add it to the long list of eco-horror films that came roaring out of the gate in the 1970s with pleas of respecting nature and the environment, from Frogs (1972) to Prophecy (1979), only to cause a whimper in theaters. Five decades of climate change denial foolishness later, audiences clearly weren’t ready for these movies.

Orca in-particular confused viewers at the time who went in expecting another Jaws cash-grab with a whale that goes chompity-chomp, and got an introspective piece on grief so full of soul it could move Bruce the shark to tears. Try to toss Orca into the net with other copycats like Tintorera: Killer Shark or The Last Shark all you want, but Anderson’s movie manages to crawl out of the ocean of rip-offs and stand on its own two feet. Fins. Whatever.

For one, Orca treats the title creature with an empathy that no fin flick ever has. Laurentiis was someone who always put story and character first. That shows in an opening scene that has a pair of Orcas leaping majestically out of an ocean backlit by a breathtaking sunset. Ted Moore and J. Barry Herron’s rich cinematography in this film is simply stunning. Throw in a yearning score from master composer Ennio Morricone, and Orca is firing on all cylinders when it comes to the beauty scale.

Some complain that the whale footage is excessive. I say shove those complaints up your blowhole, because this is prime character-building. This is, after all, a home invasion story in which a family is left dead and the survivor sets out for justice. That survivor just so happens to be a whale in this case, and these long sequences are the set-up to establish the happy couple before their life is harpooned.

Not that most of us need much to be on the side of the whale, but Orca tosses an anchor at our hearts anyway with a childhood-scarring moment in which the female, strung up on the side of the boat, miscarries her baby and spills it onto the deck. Kid me was not okay! While Spielberg’s shark was presented as a deadly force, this Orca feels human (their brains are more complex than ours). Whether it’s the ominous shots of anger in his eye, his screeching howls upon witnessing the heinous crime committed against his mate, or the heartbreaking funeral procession in which he and other whales push the murdered female to shore, you can’t help but feel as aggrieved as the whale. That’s just good filmmaking.

What has kept this a fascinating favorite of mine since I was a kid is that, despite getting us to cheer for the Orca like we’re cheering those attacking the yachts of billionaires (eat the rich), Orca challenges the audience’s perception of hero and villain. Nolan’s killing of the female makes him an asshole. No denying that. I’m even with the fishing village after the whale sinks every boat but Nolan’s and they threaten him to face the Orca on the sea or else. His refusal comes across as cowardice…until we learn he lost his wife and child to a drunk driver.

While listening to the sounds of the whale, pseudo-romantic interest Rachel asks Nolan what he’s saying, to which he responds, “You’re me, he says. I’m you, he says. You’re my drunk driver, he says.” There’s not a Jaws rip-off in existence with dialogue as heart-wrenching as that, delivered with a profound, sad performance from Harris. They share a grief that allows even a self-proclaimed dumb-dumb like Nolan to see the whale as something more than just “a fish” (Orcas are marine mammals, by the way).

The thematic undercurrent of Orca pulling audiences under suggests that, for as smart as humans or whales may be, their common flaw is the need for vengeance. An emotionally complex character herself, Rachel reminds Nolan that the male Orca is grieving, and like a human, what we want in grief is not always what we should have. Shot in some of the largest water tanks in the world in Malta, the whale leads Nolan and his crew into the Arctic for their final showdown once he’s eventually forced to accept the Orca’s challenge.

Mario Garbuglia’s jaw-dropping production design covers the boat in ice, a metaphor for the cold despair that lies at the heart of revenge. And though the whale gets what he wants, Orca by no means leaves the audience feeling content. Instead, the final images from the whale’s POV as he swims beneath the ice, unable to come up for air, imply that the whale’s plan was always to die with Nolan. In the end, no one wins. Except for the filmmakers, if their intent was to leave viewers balling. They get me in every revisit!

None of that is to say that the Orca’s vengeance isn’t justified—it totally is—only that Orca features superb writing and character development that blows most of its brethren out of the water. Nolan surprises the audience by not quite being the Captain Ahab type he first appears to be. His growth is an example of how we should feel, unlike the jerks out here saying that whales are not our friends. They are! The question is whether or not humanity deserves their friendship.

Viewers can’t be blamed for drowning in confusion over expecting yet another Jaws knockoff and receiving a tale with 20,000 leagues of emotional depth. But as Orca approaches its 50th anniversary in a few years, and as life imitates art with current events, the film is long overdue for appreciation from modern audiences. Between a cast that includes Bo Derek in an iconic scene that brings the house down (literally) and should’ve-won-an-Academy-Award-during-his-career actor Will Sampson, Morricone’s gripping score and striking whale animatronics superior to Jaws (admit it), the wave of copycats that proceeded Spielberg’s film just don’t get much better than Orca.

It’s also about time society takes the film’s messaging to heart and recognizes animals as co-inhabitants of this planet, not things to do with as we please. As Carol Connors’ lyrics in Morricone’s theme emphasize, “We are one.” But until the rich abusing nature for their own greed come to understand that, I’m going to keep pointing to Orca and welcome our new whale overlords.

Categorized:Editorials