Tobe Hooper: Celebrating the Legacy Of A Horror Hero

There are many names that we associate with the horror genre for their work and lasting influence: Wes Craven, John Carpenter, David Cronenberg, and many more. Their names register as directors who have pushed the limits and left an indelible mark on the genre that we all love. One name that also stands out is Tobe Hooper. A handful of his films are stone-cold classics that had sweeping effects on horror as a whole, and his authorial touch continues throughout his entire body of work. Today, on Hooper’s birthday, I’d like to look at his career and what it means for horror as a whole.

Texas and the Saw: An Opening Trilogy

Hooper started his career as a documentary cameraman and professor in his hometown of Austin, Texas. This work would go on to inform his very first film, Eggshells. The film follows a group of hippies that move into a haunted house. While this sounds like a fairly normal setup, the film reaches deep into hippie culture while also reflecting its horror through the lens of the French New Wave. It is an ethereal and artful film that delves deep into the headspace of the youth in his generation, while also interrogating the ideas that make up that lifestyle. Even in his early work, there is a definitive voice that begins to peek through, but it would explode onto the world stage with his sophomore feature.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre needs no introduction to anyone reading this site. The film was controversial in its portrayal of horror and violence (even with a negligent amount of on-screen gore). It points back to Hooper’s work on documentaries, as the camerawork and palette of the film imply gritty realism in place of the glossy Gothic horror of the late 60s and early 70s. The film is very tightly paced and the action feels almost hermetically sealed. It feels as though the viewer is trapped in the situation just like the protagonist, Sally. This immediacy and grit combined the ideals of a theater horror film with the grime of the grindhouse.

Likewise, the film also dealt with the hippie ideals of Hooper’s generation by juxtaposing and clashing them against the hicksploitation genre. By taking the summation of his previous work and experience, Hooper managed to create something altogether new that terrified and disgusted audiences. They had to work hard to secure an R rating since the content initially led to an X (a box-office brick wall). This film is one that resonates even today, and the experience remains as terrifying and upsetting as it did the year that it was released. We talk a lot about timeless films, but this is a major establishing text of the horror genre.

Hooper would follow this with Eaten Alive. Once again, he built on his previous work while also invoking the more ethereal and metaphysical qualities of Eggshells. The film is bathed in dreamy neon and fog, shrouding the sets in an impenetrable quality that feels like an inescapable nightmare. Neville Brand’s Judd is also an iconic villain, with his short temper and crocodile pet. Add to this a disgustingly sleazy early performance from Robert Englund and you have a recipe for another (cult) classic. The film feels like a combined effort between Hooper’s previous two films, while also leaning into his strengths in making the viewer uncomfortable and his unflinching desire to evolve and change over his career.

Adaptation and Evolution

What followed this trio of classics feels like a complete pivot from his previous work: the miniseries adaptation of Salem’s Lot. The series had an incredibly high profile since Stephen King was ascendant at the time. Plus, vampires are always a popular choice of villain. Salem’s Lot has a lot of allusions to early horror, including basing the design of Kurt Barlow on Max Shreck’s Nosferatu. The film drapes itself in a gothic and overwhelming atmosphere, which plays to the strengths of the TV film. I remember catching this on TV when I was way too young and the creeping dread had a huge (and terrifying) impact on me at the time.

His follow-up, The Funhouse, would look on paper like a return to his pre-television work. The film follows a group of teenagers who are stalked and killed at a carnival. The setup reads like a stereotypical early slasher, but the execution couldn’t be further from the expectation. The film dives deep into atmosphere and tension, drawing a line in the sand between Hooper’s work and the burgeoning slasher boom. The film would be unsuccessfully prosecuted as a video nasty in the UK at the time, simply due to Hooper’s controversial image from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and trends in horror at the time.

It’s at this point that it becomes obvious that one of Hooper’s strengths as a filmmaker is continuing to change and refusing to be pigeonholed. While his work builds off his previous filmography, he frequently throws in curveballs that shake up his entire image as an auteur and lead to wonderfully weird films that play against audience expectations. This would reach its commercial zenith in his next film: Poltergeist.

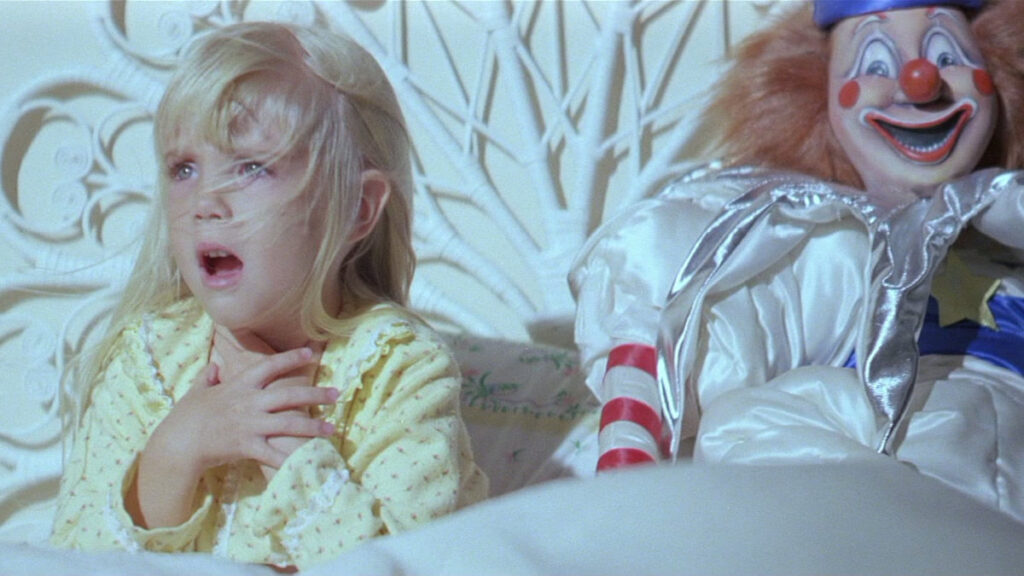

Poltergeist is another one of Hooper’s films that doesn’t require an introduction to horror fans. It is one of the scariest films of the 80s, as well as easily being one of the scariest films to ever have a PG rating. The film took the overwhelming atmosphere that Hooper had been honing with subject matter and content that would allow it to be seen by the widest possible audience. Many kids had an early brush with horror through this film, and it has influenced the strain of family ’friendly’ horror that tries to reach a younger audience.

The Canon Trilogy: Subversion and Nostalgia

After the major financial success of Poltergeist, Tobe Hooper became a hot commodity in the filmmaking world. He had created an independent flashpoint with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and had followed it less than a decade later with a major mainstream success in Poltergeist. This gave him a certain amount of cultural cachet as both a powerful filmmaker and a viable economic workhorse. Because of this, he agreed to a lucrative three-film contract with Canon Films. The only requirement was that one of the films would be a sequel to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. With this financial backing, Hooper would create some of the most strangest mainstream films of the 80s.

The first film was the operatic sexual nightmare called Lifeforce. The film is a big-budget spectacle of sexy space vampires, high-level effects, and metaphysical implications. The film was a bomb on release, but has become a cult classic in the years since (this will be the first time I mention this, as it will seem a continuing refrain from here on out). Lifeforce has an incredible sense of scale, while also pulling the terror down to the granular level of human sexuality and intimacy. The film manages to feel small while remaining grandiose, and it creates a singular experience that only gains power over the years.

This was followed by Hooper’s remake of Invaders from Mars. He loved the film as a child and wanted to create a modern version that could have a similar effect on the kids of the time. The film ends up feeling like a kid-friendly, albeit incredibly dark, combination of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) and the more serious Jim Henson Company productions (I’m looking at you, Dark Crystal). The film references the 50s sci-fi horror that Hooper grew up on while updating it for the audiences of the 80s. Furthermore, the creature design by Stan Winston is some of the most innovative and beautiful of his whole career.

With these two films out of the way, he had to deliver his sequel to the film that made him in the first place. What we ended up getting couldn’t be further in tone and content than its predecessor, but The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 pulled away from expectations to create its own style of horror. The film leans into the dark humor of the original while pushing it to logical extremes. The film is gory but in a sly, winking manner. It seems to reach for the violence that people imagined in the original film, but disarms it through tonal humor and strangeness. It also gave us Dennis Hopper in a chainsaw duel, of which the value to human culture cannot be measured in budget or box office.

Unfortunately, none of Hooper’s Cannon films would turn the expected profit executives thought they could pull out of the contract. However, Hooper spent the time creating the films that he wanted and we are lucky to have these films available to us. It would, however, lead to a change in the type of films that he would make for the rest of his career.

The 90s and Onwards: Underappreciated

Hooper’s work after this point is generally overlooked and downplayed. The lowering of his average budget along with the type of projects that he would take don’t seem to have caught fire with viewers the way that his early and middle period had. However, I would like to dispel this notion and look at the films through the lens of his career and his art. While circumstances may have changed, Hooper’s passion and love for cinema never wavered.

This can be seen in Hooper’s first film of the 90s, Spontaneous Combustion. The film currently doesn’t have a legal streaming release or high-definition physical release. However, Spontaneous Combustion is a beautifully shot and conceived film that plays to Hooper’s strengths. The film follows a man who was born during nuclear testing, played by horror royalty Brad Dourif, and his journey into self-discovery and body horror.

This is accomplished by making a film that feels like a Cold War Scanners that reaches back to the science-gone-wrong films of the 50s. This can be seen in a visual fashion as the film starts with the technicolor palette of the 50s in the past scenes, while the color drains to bright blues and deep blacks to highlight the flames that the protagonist can create. The film deserves more, and I hope to see it get a high-quality release befitting the quality of the film.

This was followed by Night Terrors, a psychosexual nightmare that brings back Robert England as a sadistic descendant of the Marquis de Sade. The film is smaller than that idea suggests, while also diving deep into the nightmares and dreams of human sexuality. A slower film that makes great use of its Egypt setting, the film is made difficult for viewers due to the visibly lower budget than the previous films. The film is worth checking out, and its dive into sex and violence make it more thematically interesting than the smaller scale would imply.

In 1995 Hooper would make The Mangler, his second major adaptation of a story by Stephen King. Robert Englund returns in this story of a possessed laundry press. Hooper makes the most of the original story, leaning into the ludicrous nature of the plot while allowing his mastery of atmosphere to amplify the idea of the threat itself. It is a b-movie of the highest order: a silly idea played straight with a reassured filmmaking touch. The film is due for a reappraisal and would appeal to those who can look past the bonkers source material to the carefully handled filmmaking that makes it work at all.

The B-movie magic would continue with 2000’s Crocodile. The film essentially posits the question of what would happen if a bunch of fuccbois decided to agitate a mother croc while partying on a houseboat. Crocodile is indicative of its era with obnoxious characters and rough CGI, but Hooper subverts this through the earnest love for the natural horror film and the mean-spirited dark humor that makes the viewer cheer for the crocodile. This is a personal favorite. It used to play regularly on the Syfy (then with the anachronistic Sci Fi name) Channel and led to my love of the natural creature feature.

Hooper’s last features seem to me like a summation of his career so far. The remake of The Toolbox Murders plays up his image as a slasher/killer director while shying away from the full grotesque nature of the films that were emerging at the time. Likewise, Mortuary leans into the small-town anxieties inherent in his early dealings with hicksploitation while also layering on family themes. Not only that, but it is the director’s only brush with the zombie genre.

His two films for the Masters of Horror series (Dance of the Dead and The Damned Thing) are notable for allowing him to cut loose with no concern for financial viability or audience alienation. These two are some of his strongest late-period work and are, in my opinion, mandatory viewing in Hooper’s oeuvre. His final film, Djinn, was an Emirati production that reached towards his style of Poltergeist and The Funhouse. Sadly, he would pass only a few years later.

You, The Reader: A Challenge

We all have our ideas of Tobe Hooper the man, the director, and the artist. There are films that have left an unmistakable mark on horror as a whole, but also there is a bounty of triumphs that fly beneath the radar. What I’d like to do to commemorate Hooper’s life on his birthday is to ask each and every one of you to seek out a movie from Tobe Hooper that you haven’t watched before and to give it an honest shot. I spent the previous week watching his entire filmography, and gained a greater appreciation for the man because of it. Clear your mind of preconceptions and try to see the filmmaker through the film itself. Tobe Hooper changed horror irrevocably for the better, the least we can offer is the appreciation and examination of his entire career.

Categorized:Editorials News