“She Might Have Been Happy with Me”: Queerness and Disability in Wilkie Collins’ ‘The Moonstone’ [Abibliophobia]

Welcome to Abibliophobia, the monthly column where Katelyn Nelson digs into the connections and influences buried deep within the world of the written word and its far-reaching tendrils across media. Focused broadly on horror and the ways it sneaks among the pages, each month will explore a new book or series and its impact on our culture, through the lens of history, the relationship between film and literature, and what varying adaptations have to say about how we understand and recreate stories. So curl up by the fire and crack those dusty covers open. We have a lot of exploring to do.

There’s a running joke in my family that if they had known how much I loved books when I was a (borderline nonverbal) toddler, my collection would have started years earlier. To this day my most persistent defining characteristics to new encounters are my love for books and horror movies. Seems only natural that I should end up with a column dedicated to exploring the connections between the two. I can’t promise the books in this column will always be horror; only that they will always be picked apart to find the things beneath the surface that speak the most to me. But don’t worry, even when they’re not, they are, at least a little.

While I make no effort to follow any particular timeline or sequence, it seems only fitting that I should open this new adventure with what is regarded as the first detective novel, Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone from 1868. Horror has its tendrils and its seeds in all sorts of genres. Though there’s nothing outright horrific in The Moonstone as we consider horror today, there was plenty of tension and villainy at its center.

Collins’ work—including and beyond this novel—was so vehemently consumed you could do any number of case studies on Victorian fan culture and the conversation between different media adaptions of the same story using his work alone. Collins was unusually revolutionary in several areas when it came to his stories. He frequently centers the women of his works and takes no qualms in having at least some of them follow rather “queer” lifepaths of independence. Collins allows them space to speak their minds in whatever tone they chose. He also, quite often, interwove disability narratives that were sometimes tragic but not strictly confined to the villain arena. The Moonstone alone features at least two—arguably three—disabled characters without whom the novel’s mystery might not be solved, and not a single one of them is the villain. Two of them, however, are queer.

If you’ve never read The Moonstone, I can’t recommend it enough. But I also must take a moment to warn that there will be a sprinkle of plot spoilers ahead. I first encountered the novel in college, and had never quite read anything like it despite a steadfast dedication both to Victorian horror specifically and detective novels generally. It’s a remarkably approachable work more interested in drawing you into its characters’ lives than bogging you down with weighty and outdated phrasing.

The Moonstone is an epistolary novel. That means it’s told through a collection of documents and letters collected to present the case in one cohesive line from the point of view of each respective witness. It details the case of a “cursed” Hindu diamond stolen during wartime by one John Herncastle and gifted to his niece years later as a birthday present (and possible act of revenge for a social slight committed by Herncastle’s sister).

The diamond is said to bring ill luck to everyone who comes into possession of it until its rightful return to the statue of the god from whose head it was stolen. Rachel Verinder, Herncastle’s niece, is, naturally, entirely unaware of the diamond’s origins and delighted to receive the gift. Her suitor, Franklin Blake, is fully aware and wary of what may come from Rachel’s receiving the gift. He’s torn with being charged as the one to give it to her on her 18th birthday. When it is stolen from her room on the night of her party, an investigation is launched to find the culprit and locate the diamond before the mysterious “Indians”—brahmins from the diamond’s native country charged with tracking it down and returning it—can steal it back.

As the mystery unfolds, we encounter all sorts of characters. There’s the steadfastly dedicated butler and Robinson Crusoe reader, Gabriel Betteredge; the servant woman with a humpback and checkered past, Rosanna Spearman; the doctor’s assistant with the unusual appearance, Ezra Jennings. Each and more gets a turn at divulging their unique perspective on the night’s events. What it all adds up to is just as surprising an end today as it was in 1868. While every character, no matter how minor, ultimately plays a hand in the mystery, there are three in particular I find most worthy of analysis: the maid Rosanna Spearman, her friend Lucy Yolland, and the doctor’s assistant Ezra Jennings.

Rosanna Spearman is the first of The Moonstone’s disabled characters. She is perhaps the most tragic, but also one of the most important. In love with Franklin Blake at first sight, she feels doomed to a life of unhappiness thanks not only to their difference in caste but her disfigured appearance due to the hump on one side of her back. In her eyes he can hardly bear to look in her direction, much less speak directly to her. While the novel is naturally woven with misinterpreted and misunderstood communication, it is also abundantly clear that the men wandering around the Verinder estate and neighboring beach can hardly fathom Rosanna’s ability to be in love with anyone, much less a man above her station.

Indeed, our first introduction to her is as an outcast among the rest of the staff. It is worth noting that they avoid her because they think she considers herself above them, not because of her appearance. In fact, the only men who even directly divulge feelings about her appearance are Franklin Blake and Betteredge. Betteredge specifically looks out for her all while expounding repeatedly about her “plainness” and laughing at the idea of her love for Blake.

However, she is seen by others. Rosanna’s word is the first to set the novel on the path to the truth. Though she ultimately ends her own life at the ominously named Shivering Sands under the pressure of never being seen by the man she loves, she is also one half of the novel’s most blatantly (for the time) queer relationship triangle.

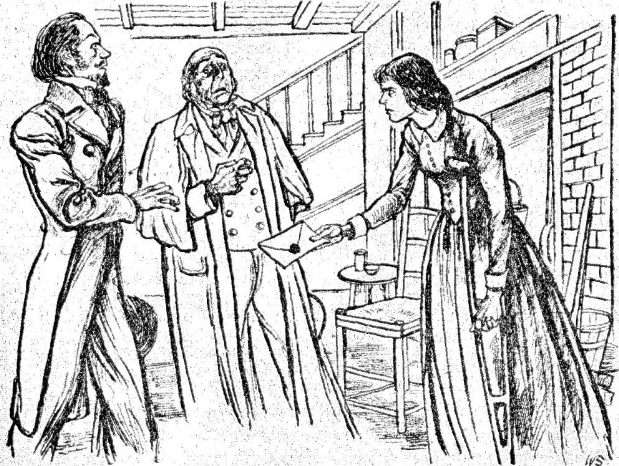

While Rosanna mourns that her disfigured appearance leads Franklin Blake to hardly ever spare her a glance, Lucy Yolland is not only otherwise regarded as beautiful, but also as Rosanna’s only friend. Lucy is a fisherman’s daughter who lives on the other side of the Shivering Sands and is usually referred to as Limping Lucy thanks to her use of a crutch. Every page in which Lucy and Blake interact or in which Blake is mentioned to Lucy is woven with her pining mournfully for her lost “darling” whom she loved and had plans to run away and “live by the needles” (191) with. Lucy is, in fact, the first person in the novel to expressly proclaim love, and she does so unabashedly for another woman. The truths Rosanna has to reveal come to us through Lucy’s hands and are painted with Lucy’s pain.

The mystery of the lost diamond is coated with blood from the first page to the last. But it is the blood of Rosanna and Lucy’s pining hearts that is the most tragically shed. Yet it’s fascinating that Collins chooses to rest his most important reveals in the hands of his queer disabled characters.

Ezra Jennings, the third disabled and second queer-coded presence of The Moonstone, is the force that brings the full truth of events to light. He also suffers through his chronic terminal illness and faces the mysteriously enticing force of Franklin Blake. In true Victorian fashion, Blake is the well-traveled and well-meaning male center of the story. So perhaps it makes sense that he should be the downfall of one and the saving salve of another. Blake and Jennings are drawn to one another. Tough on Blake’s part, it’s due to Jennings’ unusual “piebald” appearance. Where he can hardly remember Rosanna’s presence in a room enough to register her, he cannot take his eyes off the man he believes to hold the secret to the moonstone’s fate.

There are varying degrees of disability that get noticed in the world, from Victorian times to the present. Obvious disfigurement like Rosanna’s hunchback and Lucy’s crutch-aided limp would ordinarily draw at least as much attention as a man who probably had vitiligo. Yet here Jennings draws the most. It’s an unusually diverse range of disabilities to pull together. And it’s an even more interesting range OF responses to consider.

In any number of other novels by any number of other authors from the period, Rosanna’s hunch and Lucy’s limp would condemn them to a life of villainy and labeling as madwomen. Jennings would likely be cast in any number of racist monikers. Yet, under Collins’ pen, Rosanna’s history as a thief is expunged. Lucy is the mourning messenger. Jennings is the ultimate conveyor of the reveal. Each of them, in their own way at their own times in the novel, is instrumental to the story. Without even one of them, you would have an entirely different experience. Without any of them, the novel would not be half as engaging and empathetic.

It is also important to note, that in The Moonstone and several other of Collins’ disability-centering works, the disabled characters are given their own voices to tell their own stories. Rosanna’s note to Franklin Blake following her death is read in full. When Blake asks Betteredge what the first lines—in which she plainly states “I love you”—could possibly mean, he responds, “Please go back to the letter Mr. Franklin…let her speak for herself” (317).

Jennings is the second most significant controller of his own narrative. Both he and Rosanna choose who and how their stories are told. In his case, Jennings chooses to leave the thing which follows him and casts his name in shame a complete mystery to everyone. He leans instead toward the pursuit of a final good act that would settle the care for his loved ones after he succumbs to his illness. His encounter with Blake, easily read as a queer infatuation just the other side of Lucy’s for Rosanna, is, in his own words, the last “happy time” before his passing (430).

Even today, it’s not often that disabled characters get to have the spotlight as heroes and benevolent forces. There are still more disabled characters playing yet more pivotal revealing roles I have not even mentioned. It’s also not often that queer disabled characters get to fully exist. Collins’ move to center them and make them pivotal to the story of The Moonstone was years ahead of his time in many ways, but it also proves a point.

Whether you consider detective fiction a predecessor or an offshoot of horror, the genre has always been queer before it was anything else, sometimes despite the people trying to pen or consume it. Wilkie Collins stayed reminding audiences—even when he had disabled villains—that disability does not make anyone less worthy of the same space, consideration, and love that’s given to their counterparts.

Categorized:Editorials News