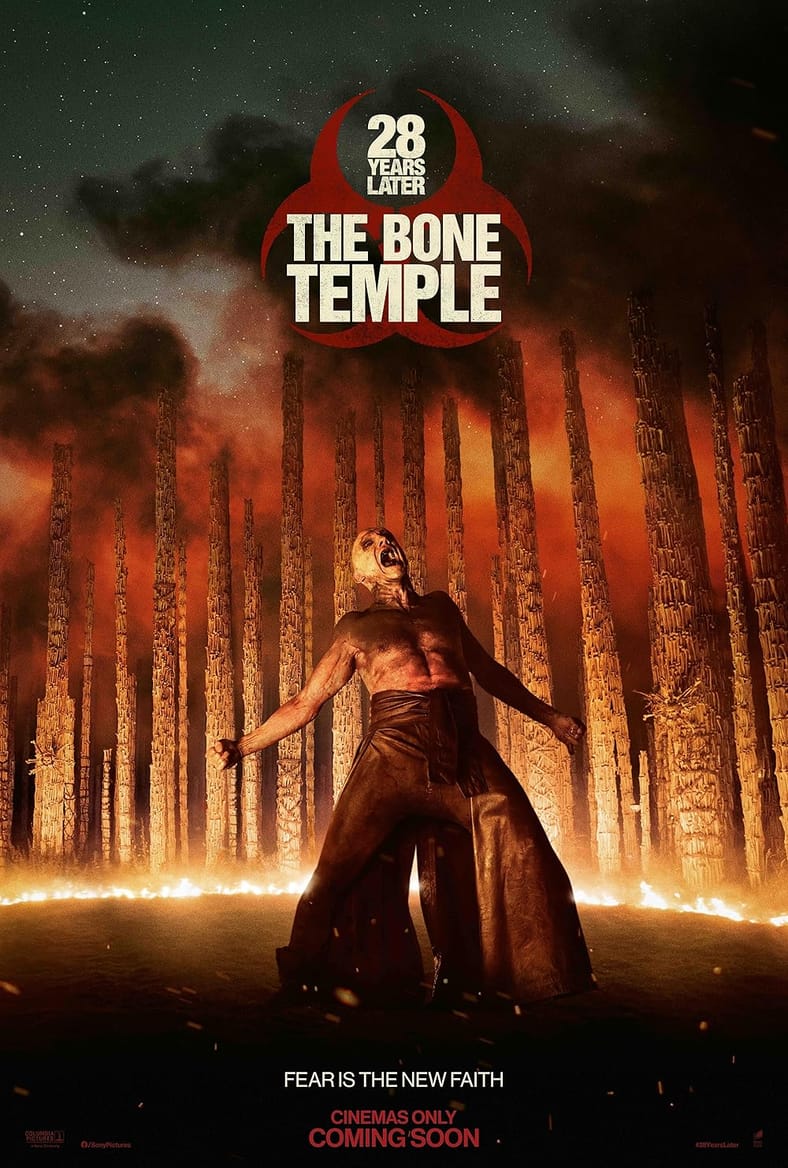

Nia DaCosta On Building ’28 Years Later: The Bone Temple’ [January Cover Story]

Nia DaCosta is a certified master of horror. In less than a decade, she’s emerged as one of the medium’s most fearless directors—a filmmaker who understands that fear isn’t just about spectacle, but about control. For Dread Central’s January 2026 Digital Cover Story, I sit down with DaCosta as she reflects on a body of work that has steadily redefined what studio genre filmmaking can accomplish, from energizing urban legend and legacy horror in Candyman to perfecting the punishments of both fear and faith in 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple. See my 5-star review of the film.

Rather than treating legacy material as something fragile or sacred, DaCosta approaches the stuff with confidence, expansion, and yeah … risk. All of that tension runs through 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, where she anchors the film not just in apocalyptic dread but also in its satellite ensemble of deeply thrilling character studies.

Central to that is Erin Kellyman’s performance—one DaCosta had been tracking long before this project. In The Bone Temple, Kellyman plays a character unraveling internally. “She’s someone who’s sort of losing her faith. She’s losing her religion, and it’s very dangerous to be doing that in the context in which it’s happening,” she says, noting how repression becomes a devastating survival mechanism. “So much is under the surface because she’s repressed so much because of the horrors she’s living through.”

That balance of terror and control carries into the film’s villains as well. Reflecting on Jack O’Connell’s work and becoming a cultural phenomenon mere months after filming with him on The Bone Temple. DaCosta says, “I was just so excited for everyone to see him play yet another diabolical and entertaining character.” What fascinates her is the contradiction. “There’s a darkness and he’s terrifying, but also there’s a humor to him.”

But humor, in DaCosta’s films, isn’t comfort. “You’re sort of being lulled almost into this weird space,” she explains, “and then something horrifying happens.” Rather than releasing tension, comedy sharpens it. “It’s not quite a pressure valve,” she says. “The humor… is just a part of the madness.”

Still, even DaCosta has limits. While she’s unfazed by extreme violence—“Flinging, skinning, beheadings, eye gouging, bloodletting, bones breaking—I’m cool”—one image still turns her stomach. “The most disgusting thing in the film is Samson having bits of brain in his beard,” she says. When I clarify if the brain has anything to do with her repulsion, she laughs, admitting otherwise. “Food in the beard…and I’m disgusted.”

World-building, for DaCosta, often comes from instinct. One of the film’s most striking locations wasn’t in the script at all. “That location was not in the script,” she says of the abandoned indoor pool from the film’s nightmarish opening sequence. “I saw the picture of it, and I was like, this is really cool.” What sold her was the contrast. “There’s something really interesting about introducing these terrible characters in a place that is for children, essentially.”

And above her worlds, DaCosta’s use of inverted skies and destabilized space is one her most disquieting ongoing visual choices, and it landed with particular force for me—I have a mild phobia of open spaces, the kind that makes vast skies feel unmoored and unsafe, which is why this imagery in both Candyman and 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple was so personally striking. For DaCosta, however, the effect isn’t about repetition or flourish.

“I don’t know if I’ve done that on purpose,” she says, pushing back on the idea of a recurring motif. With The Bone Temple, the goal was atmosphere as much as unease. “It was really about trying to portray something that felt beautiful.” Her approach in Candyman was more deliberate—a response to legacy. “The drone is not special anymore,” she explains, referencing the original film’s iconic aerial shots. “So what if we just flip it on its head—which is what the movie’s doing.” For DaCosta, those upside-down skies aren’t decorative but thematic. “All those visual things kind of always, for me, come from the themes.”

When DaCosta takes big risks, she commits fully. The film’s musical sequence initially scared her. “I was anxious about it when I read it,” she admits. But by the time it was shot, that fear disappeared. “By the time we were shooting it, I just had so much confidence in what we came up with.” Seeing the early cut sealed it. “I was like, okay guys—you pulled it off. We’re good. We did it.”

Asked about horror films that made her feel anything was possible, DaCosta doesn’t hesitate. “I put Under the Skin on, and I had no idea what it was about,” she recalls. “It was one of the most compelling things I’ve ever seen.” What stayed with her most was its refusal to explain itself. “It’s a movie about an alien, but it’s also a movie about being a woman and having a body.” The final image still resonates. “I was like, this is just genius.”

For DaCosta, films like that are proof of possibility. “Every time I see a film like that where it’s just outside of what the norms are,” she says, “I get so heartened. We can do anything in this medium. It’s so open.”

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple is in theaters January 16, 2026, from Sony Pictures.

Categorized:Cover Stories News