Housing Insecurity Makes DREAM HOME a Terrifying and Relevant Slasher

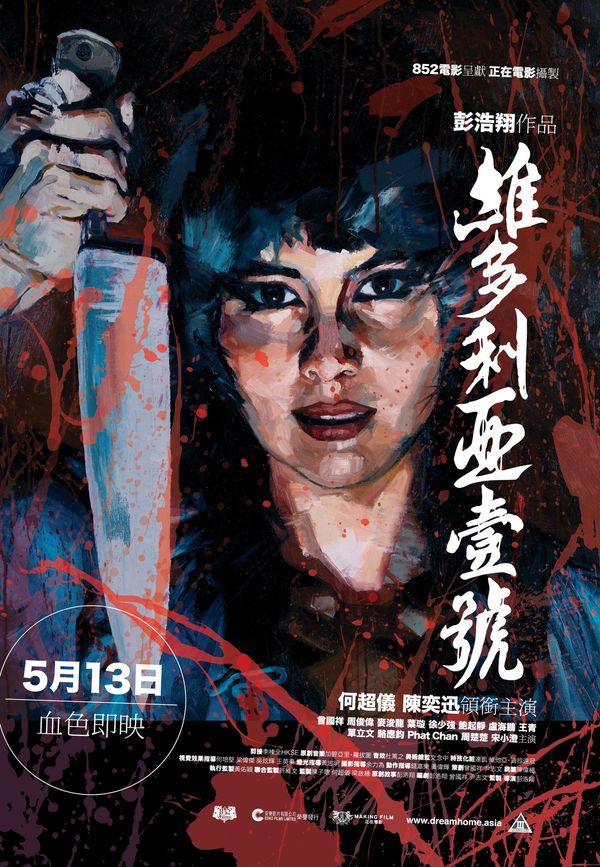

Horror has a curious way of refracting real-world horrors with such prescience and lyricism, the lingering, residual effects are often more haunting and troubling than whatever is shown on-screen. Like Nostradamus and his almanac, horror is poised more than any other genre to both simultaneously predict, diagnose, and assuage the horrors of the real world by dint of genre convention and narrative mechanics. Dream Home, a slasher movie hailing from Hong Kong released in 2010, was infuriatingly poignant and conscious at the time of release. In the eleven years since, Dream Home has only grown in its relevancy and diagnostic power. It’s slick, cruel, and in the context of our world now, altogether crushing.

Also Read: 5 Fantasia Films We’re Excited to Check Out

In Hong Kong, Cheng Lai-sheung (Josie Ho) is working two jobs, desperate to save up enough money to buy an apartment of her own. Not just any apartment, though, but one with a view of the Victoria Harbour, a natural landform in Hong Kong that separates Hong Kong Island in the south from the Howloon Peninsula in the north. Told in mixed-chronological order, we follow Lai-sheung’s early adolescence, which includes her unfulfilled vow to purchase her parents a new home, the death of her mother, and a traumatic eviction where Lai-sheung and her family are thrown from their low-rent project to make room for developers to erect expensive, high-rise flats.

The early goings are an earnest and heart-rending affair. Just as Lai-sheung seems close to securing enough for a mortgage, her father loses his insurance or his medical bills skyrocket. The banks, too, are hesitant to approve her, and her own boyfriend refuses her a loan. It’s a discouraging sentiment, one not unlike the perennial notion that for all one’s wants and needs, the world simply doesn’t care. The world chugs along, the rich get richer, and Lai-sheung continues working herself near to death for what appears to amount to nothing. For all her years of work, nothing has changed. If anything, it’s simply gotten worse.

Also Read: FEAR STREET PART 1: 1994 Makes for a Glorious Queer Throwback

One evening, her father has trouble breathing, and rather than saving him, she lets him die, confident that the insurance payout would finally be enough for her to purchase the new apartment. On her way, though, a stock market snaffu swiftly raises the property value, and once more, Lai-sheung is priced out of her dream home. Resultantly, Lai-sheung spirals into a frenzy, attacking the people who live and work there in a gruesome, gonzo series of violent deaths and slasher gore. Seriously, Dream Home is incredibly violent. The deaths hit hard, rendered with calculated practical effects and prolonged sequences of torture and suffering as Lai-sheung makes use of conventional domestic products (including a vacuum cleaner) to kill everyone in her way.

The victims are a dopey bunch, portrayed as clueless yuppies inexplicably unaware of the poverty that exists just outside their building. It’s darkly comic even if, on occasion (including the death of a pregnant tenant), Dream Home perhaps goes just a bit too far. In the end, Lai-sheung can secure a unit for considerably less than expected. After all, there were eleven murders there the night before. She stares out into the harbor as a news broadcast comes on detailing America’s worsening mortgage crisis and the ever-expanding global repercussions.

Director Pang Ho-cheung and writers Jimmy Wan, Derek Tsang, and Pang Ho-cheung wisely avoid indicting Lai-sheung, allowing her to get away with her crimes and, yes, secure her dream home. Any repercussions or consequences will live within her. She won’t be arrested or denied entry. There’s no final-twist that renders her massacre for naught. She is successful, full stop. It’s certainly a controversial ending, though portrayal doesn’t often equate to condonation. Certainly, the filmmakers are not encouraging home buyers slice and dice their way to their dream unit. Instead, like with Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar-winning, horror-hybrid Parasite, Lai-sheung’s actions highlight swelling inequality. The developers and tenants, intentionally or not, have displaced and killed dozens of low-income persons in the neighborhood. They’ve eroded natural landscapes and priced residents, some generational, out of their homes. What’s eleven deaths compared to decades of suffering?

Housing insecurity is one of the most terrifying things a person can experience. It’s enduring and parasitic, infecting every other part of a person’s life, from education, to family, and workforce participation (try applying for a job without a permanent address). As America’s own housing crisis swells, in part because of decades of inequity, and compounded in part by the COVID-19 pandemic, Dream Home is especially piercing. It’s a furious, blood-curdling exhibition of rage and incendiary justice. It’s desperate people resorting to desperate measures. It’s profound, uber-violent, and giddily uncomfortable. It also, with every day that passes, feels closer to reality than it should. If you ask me, that’s the hallmark of good horror.

Categorized:Editorials News