Ultra-Indie Spotlight Sunday: Project Zomboid

Project Zomboid takes place in the suburbs outside Louisville, Kentucky. The entirety of Knox County and beyond has been subjected to a cataclysmic zombie apocalypse. You take the role of the last survivor of the Knox Infection, and soon that role will no longer be available because there is a completely certain 1000% definite undeniable predestined guarantee you will die.

Conceptual Meta-Wank:

There’s something so intriguing about a game that can’t be beaten. Tetris is the obvious example of fighting against futility, and how deeply engaging and replayable that style can be. The gradual difficulty increase and frantic anxiousness that comes with progressively harder and harder gameplay is a great foundation for a horror game. While it may not be as linear a difficulty progression, Project Zomboid channels that futility into something incredible (and incredibly frustrating).

The big premise of Project Zomboid is that it is a realistic simulation, almost as realistic as it gets. That means, if you get bit, that’s it. Within a few days, you will be a shamblin’ down the way with the rest of the horde. And since for the first 15ish games, I would run into stuff I didn’t know like a zombie on its back can be stomped to death but a zombie on its front can bite your ankles, or sometimes smashing a window will set off a home defense alarm, I was either devoured outright or escaped, only to check my health tab and see I got bit on the leg and the character was doomed. But it did teach me a new valuable lesson every time I played, and before long I was able to survive a few days and even a week before I made a goof and wound up with a zombie hickey sealing my fate.

Non-Wanky Game Recap:

.

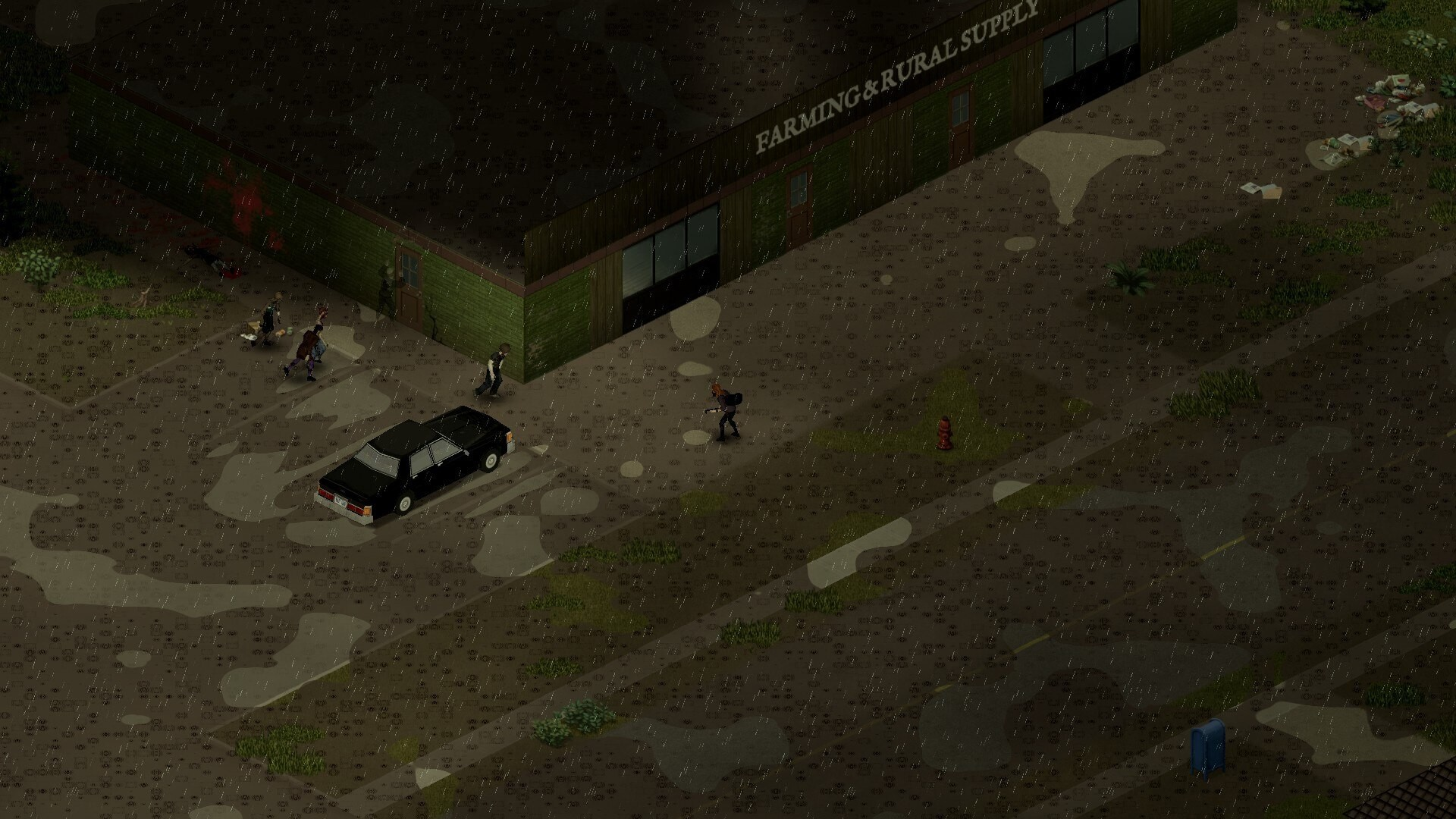

Project Zomboid is an isometric survival horror. After building your character, you’re dropped into a random house in Knox and off you go. You can search for a rolling pin or water, rip up some sheets for makeshift bandages, and grab some canned food in the hopes you’ll find a can opener soon, and off you go into the wild apocalyptic suburbs. Most of the time, you will be sneaking around with a garbage back full of junk in your hand, but once the horde is alerted, it’s time to ditch your stuff and run for your life.

What Works:

To say Project Zomboid is a realistic simulation is to put it lightly. Everything but bowel movements comes into play. I found myself with pop-ups warning me of the regular alerts—hunger, thirst, exhaustion. However, I was also faced with sweatiness, boredom, anxiety, and depression to overcome (just like in real life). Managing your character’s body temperature wouldn’t have occurred to me, but hey, putting on a fireman’s jacket to run around in the Kentucky July heat would certainly give me a debuff.

Of course, this carries over to the more direct aspects of survival in Project Zomboid. Firing a gun will alert every zombie in the state to your location, so you’d better have a quick getaway. Fighting a zombie in melee always poses the risk of being nibbled. If you have a heavy bag of stuff, jumping over a fence to escape the shamblers means dropping all your loot and having to come back later. The water and power are running well through the houses when you start but come winter you’re on your own. Even once you’re armed and armored, PZ’s difficulty manifests in new and exciting ways. This means, the longer you live, the more gut-wrenching it is to check your health menu and see the bite marks.

What Doesn’t:

As you can imagine, Project Zomboid has a very steep learning curve. There are a truly incredible amount of systems at play, which is daunting. And the fact that you cannot save and reload adds to the daunting nature of PZ early on. This aspect is also what makes the game so cool and unique. You can’t save scum, you really have to learn to survive because you most certainly will not for quite a while.

There is, however, one thing that detracts from the hardcore finality of a game of Project Zomboid. When your character dies, you have the option to create a new character in the same map, with all the items still as is. This doesn’t mean much early on, but once you have an established and well-stocked base, it changes the dynamic entirely. If your character is bit, simply drop your bags and weapons and run nude through the streets hooting and hollering until you’re devoured, and have a new character come to take the reins. I think this is a subtle enough way to show the player some grace but does detract from my initial thesis of finality.

How To Fix It:

I would say the game is perfect and do not fix any of it. The steep learning curve makes for tremendous satisfaction, and if Project Zomboid letting your fresh character save some time by not having to rebuild a base is not your preference, then just start on a new map. PZ already lets you create a custom map anyways, you can make it as difficult or easy as you please. There was, in fact, someone on Twitter who said they disabled the zombies entirely so they could go around and fix the cars. Play how you like.

Wanky Musings:

The detailed simulation games market brings about some of the most dedicated player bases around, as friend of the Dread Dillon Rogers (developer of Gloomwood) points out in this Tweet which more or less inspired me to buy this game. Players love a challenge, and more challenging than overcoming impossibly huge hordes of zombies is that of figuring out the systems to help you survive. Games like DayZ and Kerbal Space Program and Project Zomboid, while not easily accessible to most gamers, provide the audience and internal sense of satisfaction that is incomparable to many triple-A titles on the market. These are games made with love (even DayZ, which I hate) and that is something to be cherished.

You can buy Project Zomboid on Steam by clicking here.

Categorized:Ultra-Indie Spotlight