‘The Backwards Hand’ Author Matt Lee On Disability, History, and Memoirs

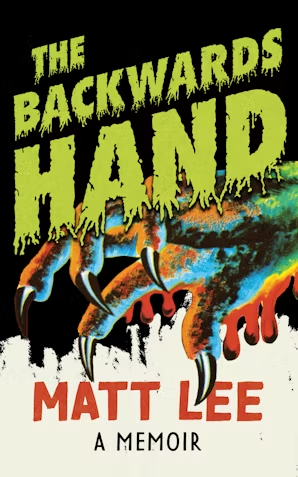

Disability representation is severely lacking in all media, full stop. But horror especially has a weird relationship with disability as so often disability isn’t necessarily ignored, but it is villainized to create some of the genre’s scariest villains. We’re terrified of the other, of someone who looks and/or behaves differently than us, so it’s a natural fit for the genre, right? But what happens when a person with a disability sees that film or series and realizes, “Oh, everyone thinks I’m a monster”? This is what author Matt Lee works to interrogate in his memoir The Backwards Hand, out now from Northwestern University Press.

Read the full synopsis below:

Told in lyric fragments, The Backwards Hand traces Matt Lee’s experience living in the United States for more than thirty years with a rare congenital defect. Weaving in historical research and pop culture references, Lee dissects how the disabled body has been conflated with impurity, worthlessness, and evil. His voice swirls amid those of artists, criminals, activists, and philosophers. With a particular focus on horror films, Lee juxtaposes portrayals of fictitious monsters with the real-life atrocities of the Nazi regime and the American eugenics movement. Through examining his struggles with physical and mental health, Lee confronts his own beliefs about monstrosity and searches for atonement as he awaits the birth of his son.

We spoke with Lee about his new book and the experience of combining memoir with analysis, getting deep into research, and the insidious nature of the trad wife trend.

Dread Central: Can you just tell me in your own words a little bit about what this book is all about?

Matt Lee: The book explores the relationship between disability and monstrosity. So I tell my own story and share some of my own experiences growing up disabled, and then I weave in episodes from throughout history and all sorts of references to pop culture and especially horror films, looking at the ways in which disabled people have been portrayed in the media. I’m also looking for how society’s treatment of disabled people and sort of fears and apprehensions surrounding disability is reflected in works of art from paintings, films, you name it.

DC: I really love how this book is organized because it felt like I was reading the Bible a little bit. The way that the text is formatted is lyrical, but also you’re combining personal stories with analysis in a way that really hits home. I wanted to hear more about why you chose this kind of format for the book.

ML: Yeah, that’s a great question. I love the Bible comparison. I had never thought of that, but that’s a great way to look at it. Hopefully I’m not being preachy or anything. [Laughs]

DC: Oh, absolutely not. It’s more the actual formatting of the text.

ML: Well, for starters, I’m just a huge information junkie. I have a voracious appetite for books and films. I read pretty widely, and my tastes are pretty eclectic, so I’m just constantly filtering through all sorts of information, finding all sorts of stories. So the research part of the book is always a lot of fun for me. Compiling all this research and all these different stories gives me a way to sort of contextualize my own story in a way.

I’m reflecting my experiences off others’ experiences, and I like trying to mix together very different and disparate experiences to show not only the commonalities that a lot of disabled people share in terms of their experiences, but also, and perhaps more importantly, a lot of the contradictions. The topic of disability is so far-reaching and it’s just such a broad spectrum. It’s impossible to fit it neatly into a box. So I felt that the form could mirror that in a way, by being chaotic and slippery and messy. It’s a deluge of anecdotes and quotations and references that, again, I want to sort of overwhelm readers in a way to mimic some of the experiences of living with disability, if that makes sense.

DC: Absolutely.

ML: Yeah. So kind of organized chaos.

DC: I think that’s a good way to put it though. It is organized chaos, but in a way that I think brings attention to disability in ways that people don’t even think about. Again, you’re not just talking about horror movies, you’re talking about paintings, photographs, everything. And I think this is such an effective way to talk about disability. So often people think about disability as a monolith and that is so patently false. This is a really good text in terms of confronting that in a way that’s also accessible to all readers.

ML: I want to push against that stereotype you mentioned. I think that’s important. I’m glad you feel that it’s successful because I wanted to, stylistically, use a pretty measured, plain-spoken voice. It’s not, like you said, academic jargon or anything like that, although some of the topics might veer more toward academic or intellectual.

But yeah, I think disability is a topic that gets relegated to the fringes. It’s something that, despite a lot of the progress we’ve made, people are still apprehensive to talk about it. It’s still in a lot of ways taboo. And again, I think it stems out of people’s fears and anxieties surrounding disability. It’s an uncomfortable topic, even though it’s also a very universal topic. So I felt it was important to, like you said, push back against that monolith. I think that’s a great way to put it, just to show that there’s a whole multitude of experiences. There’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to disability.

DC: So in writing this, what was your process? Did you write the personal part first? Did you have the examples listed? I’m just curious what that was like for you in terms of figuring out where to write what in the book.

ML: Yeah, that’s a great question. I began sort of simultaneously writing scenes from my own story, my own personal narrative, and then also starting to compile pieces of research that I wanted to touch on in the book, and that I felt could connect to my story. So I started to organize the research. I had dozens of different working documents of like, okay, here’s where I’m going to put all of my film research. Here’s everything about horror movies I’m going to write about here. Here’s everything from history and antiquity. I’m going to write about that here. Here’s where I’m writing about art or photography. Here’s where I’m writing about the Nazis and the extermination of disabled people and the mass killings.

So the pieces were all kind of separated by category, if you will. And then I started to put them together, and that process was pretty organic. I knew that my story would be the anchor of the book because I knew where it started and I knew where it was going to end. So I decided, okay, I’m going to keep my story pretty straightforward, and I tell my story in a linear fashion from point A to point B. I felt that that could help create a through line and hold everything together as I was bringing in this very diverse array of information that is non-linear.

It was just a matter of connecting the dots. I just followed my instinct and I would discover new things as I was going along. One piece would open up a door to another film or another reference that I wasn’t familiar with. Then it would balloon from there, which was very exciting when I was working on it.

One example I’ll give you is I knew going in, that I wanted to write about Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now and the portrayal of the Dwarf Killer in that film. In researching that film, I started to make some kind of surprising connections. I also knew I wanted to write about the musician Robert Wyatt. He’s a wheelchair user. And I realized in researching Don’t Look Now that Robert Wyatt’s wife was the assistant editor of that film. Wyatt was with her in Venice while she was working on the film. So there were all these surprising connections I started to uncover just tying the pieces together. That’s just one example.

But that would happen continuously throughout. At a certain point, I had to stop myself because there’s just so much out there. Once you go looking for something, you start seeing it everywhere. So once I started looking for portrayals of disability, everywhere I turned, they were popping up. So I had to be selective about, okay, what are the films or the artworks that resonate with me or that are actually part of my story? Ones that I was familiar with before I began the project and things like that.

So I had to pick and choose. A lot of stuff got left on the cutting room floor, but overall it was a pretty organic process of just trying to find the connective tissue of what ties all this stuff together surrounding my story.

DC: That’s so cool. I’m also writing a nonfiction book, and you have to really figure out when to stop researching. You’re like, alright, I’m going too deep. It’s going too far in the other direction of what I wanted to do. People don’t tell you when to stop researching.

ML: I mean, I would say put it down on paper and you can always cut it in the editing. Always save that stuff. You never know when it might come in handy. But yeah, you have to exercise a little restraint or else the book will never be done.

DC: You mentioned this a little bit with that really cool connection in Don’t Look Now, but what was maybe the most surprising thing you learned in your research that you weren’t able to include in The Backwards Hand?

ML: The most surprising were often things that were troubling, like looking into figures whose work I had admired. Then you come to find that they hold pretty disparaging views about disabled people or things like that. One example that comes to my mind is researching Helen Keller, who’s a very well-known figure. Everyone sort of equates her name with disability rights. But reading about her life, her politics are pretty contradictory to all that. She was a proponent of euthanasia and a eugenicist. She advocated for disabled babies to be put to sleep.

It’s very puzzling. She lived with disability and experienced the hardship of that firsthand and the stigma of that firsthand. Then to have her sort of turn around and be spouting this kind of fascistic, eugenicist system of views, it’s like these two things don’t add up. How do you square that? Things like that were always very surprising to me.

And honestly, I was not terribly well-versed in the early American eugenics movement, which directly fed into the Nazi movement in Germany. And then reading about that, I was often shocked about just how popular it was and how such a large portion of the American population was behind these policies. Many of these policies became federal law. So just the fact that it was so accepted and it was so widespread came as a big shock. Yeah.

DC: Yeah. It is really terrible when you start looking too closely at American history!

ML: Once you start looking close, you’re not going to like what you see!

DC: Guys, we really liked sterilization in America, and we might still, it’s terrible.

ML: Well, it’s like the Supreme Court case I write about it briefly in the book. Buck v. Bell legitimized the forced sterilization of disabled people. It’s never been overturned, it’s still on the books. So yeah, we have a lot of unsavory history to reconcile within this country, for sure. And a lot of these attitudes persist. You still see these sort of pseudoscientific, eugenic arguments in a lot of ways are starting to make a strange comeback.

Like the whole trad wife thing. That’s rooted in eugenics. It’s this idea of better breeding. We can improve the human race through breeding and we’ll breed out undesirable traits and characteristics. Now it’s a TikTok trend.

DC: It’s so much more insidious, which is even scarier. It’s hidden behind blonde hair and cute babies, which is just very bizarre to me. And

Yeah, it’s a veneer of perfection and civility, and this idea that we can create this utopian perfect world. But it’s rooted in what amounts to genocide, more or less. We’re talking about exterminating, right? Again, this is why the Nazis were inspired by this. And during the Nuremberg trials, the Nazis pointed to cases like Buck v. Bell and said, “Well, you told us it was okay. We learned from you, and now we’re in trouble for it. What gives?”

So, yeah, learning about those chapters of history, which I think a lot of people have forgotten because they’ve been sort of swept under the rug, was pretty eye-opening. And again, putting it in a contemporary context, I was like, oh wow, this is still out there. This is still around. These attitudes persist.

The Backwards Hand is out now from Northwestern University Press.

Categorized:Interviews