In Kiyoshi Kursosawa’s ‘Cure’, Stress Relief Means Murder

For the longest time, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure—one of the great unsung J-horror films never to be remade—was unavailable on home media in the U.S. The plot involves a stoic cop, Takabe (Koji Yakusho), investigating a string of murders that all bear the same M.O., despite being committed by different people with no criminal history and no connection to one another. These are average citizens whose jobs peg them as pillars of society, like teachers, doctors, and even other cops. Something has made each person snap and transgress the bounds of polite Japanese society in the bloodiest way imaginable. It would seem homicide by hypnosis is at play, in both the story and its mesmerizing power to slay the viewer’s lizard brain.

In the 2020s, other prominent Asian filmmakers have championed Cure, including three-time Oscar winner Bong Joon-hoo (Parasite), who nominated it as one of the greatest films of all time in Sight and Sound magazine’s once-a-decade poll. It wasn’t until October 2022, however, that Cure finally escaped streaming limbo when Criterion unveiled a 4K restoration of it for its 25th anniversary. In his Dread Central review, Chad Collins called the movie a “terrifying J-horror masterpiece.” If you bought the Blu-ray, you’d see two-time Oscar nominee Ryusuke Yamaguchi (Drive My Car), a former student of Kurosawa’s at Tokyo University of the Arts, interviewing the director and professing his love for Cure.

Some among us were still left thinking, “Who do I have to hypnotize to get a digital release?” Late last year, Cure finally arrived in rentable form on platforms like iTunes, so now it’s out there for the widest possible audience to see. Kurosawa has said that the concept of aimai-sa, or ambiguity, was an important one for this film. It manifests itself onscreen as the good, intriguing kind of ambiguity, not the lazy kind. You can watch Cure once and understand it intuitively before the inevitable rewatch leaves you speculating about the meaning of certain things, including the clues to an older mythology that play out on its edges. One question underpins its thematic weight: why exactly is it called Cure?

All the world’s a mental hospital

Cure opens with Takabe’s wife, Fumie (Anna Nakagawa), meeting her doctor in a mental hospital. Her unspecified condition has her doing things like running the washing machine with no clothes in it and getting lost in her neighborhood on the way to the convenience store. This sets the stage for a story where Takabe and the people in his orbit, even a stranger muttering under his breath at the dry cleaners, are struggling to maintain their sanity in a disorienting world.

Fumie reads aloud from the tale of Bluebeard, the wife-burying version of a Black Widow killer. The later scene with the empty washing machine, spinning like a frantic automaton with nothing under its lid, provides a glimpse into Takabe’s private struggle to care for Fumie at home while confronting constant inhumanity in crime scenes at work. It’s sandwiched between scenes of the ill-fated teacher bringing home an amnesiac man, and the teacher jumping out the window after butchering his wife.

This juxtaposition of subplots foreshadows Takabe’s character arc as a turn-of-the-millennium Bluebeard. In Cure, Yakusho’s depressed salaryman character from Shall We Dance? (released a year prior to great success) would become a stressed-out cop with a much unhealthier outlet for his modern anxieties. His new dance partner for this movie would be Masato Hagiwara (Chaos), who gives a chilling turn as Mamiya, a man who appears to suffer from complete amnesia of both the retrograde and anterograde type.

When Mamiya first appears, it’s on a beach in Chiba Prefecture. At first, the beach is empty. Then, Cure cuts to Mamiya’s victim, the teacher, looking out across the beach. Then, it cuts back to the previous beach shot, but we’re in the teacher’s perspective this time, and he sees Mamiya there. Gazing up at the sky like The Man Who Fell to Earth, the character shows up out of nowhere, almost as if he’s an incarnation of the teacher’s consciousness. Later, we see Takabe’s face positioned behind Mamiya’s head, and vice versa, so that it looks like they’re tumors growing out of each other’s brains.

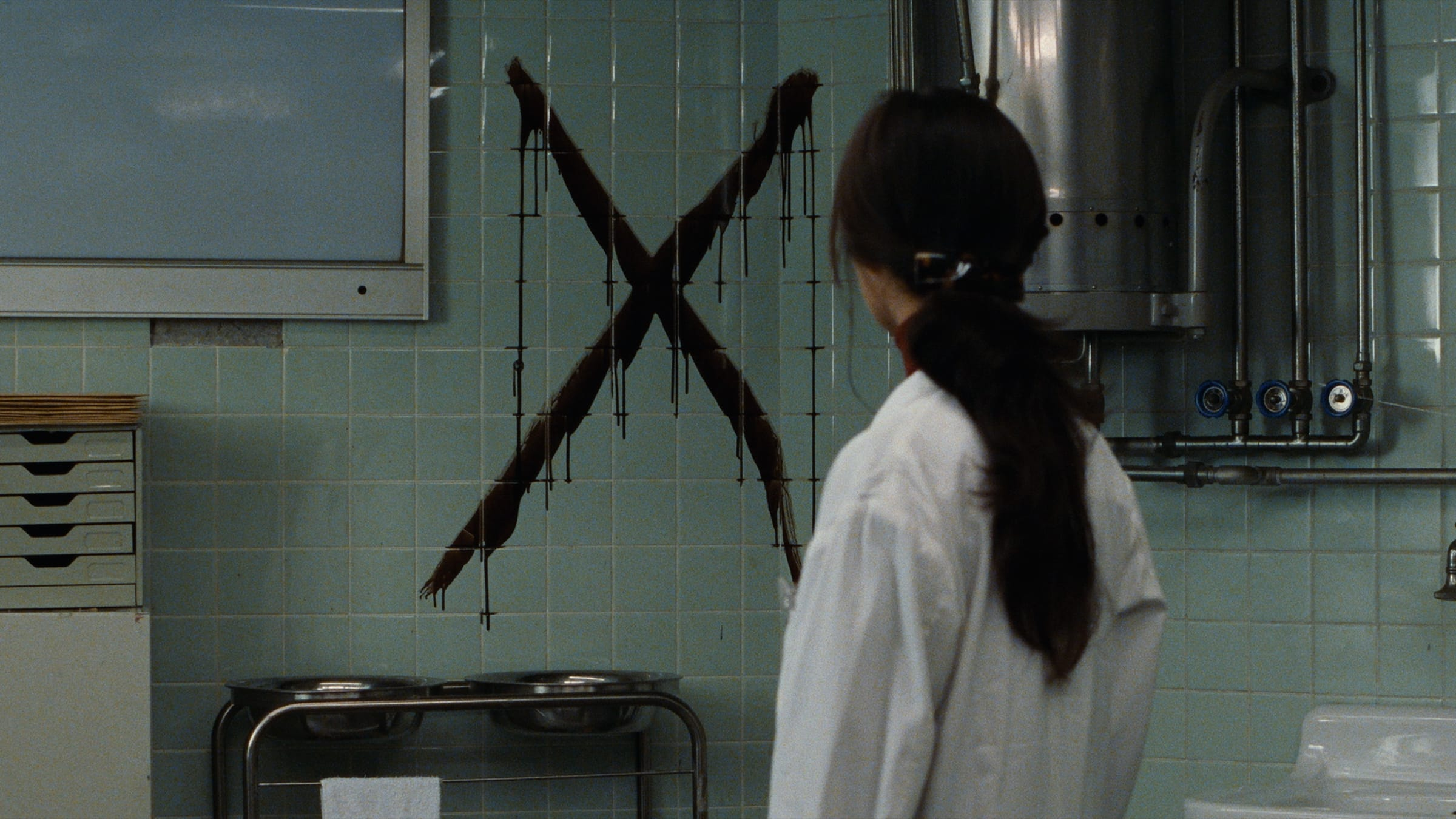

In the meantime, as Takabe begins to suspect that the killers he’s investigating might have all been hypnotized, parallel scenes with Mamiya reveal more of his methods. “X” marks the spot where the people he’s mesmerized with fire and water have sliced the flesh of their loved ones or other victims. His power over them, if not supernatural, is visibly elemental. All he needs is a relaxing voice, the flicker of a lighter here, and the spread of a spilled glass there, to lull someone into a suggestive state. Pretty soon, they’re moving around like mindless pawns. Cue the whirling-dervish home appliance.

Hypnotherapy of the id

Since he has few memories from one minute to the next, Mamiya is a slippery interrogation subject. It’s hinted his amnesia may be selective since he remembers a certain woman in a pink negligee, and he remembers that Takabe is “a detective with a crazy wife.” When an inconsistency in his pattern of amnesia emerges, he explains to the teacher, “I don’t remember anything. You do.”

That’s just what a walking id would say before he wormed his way back into your head, isn’t it? Mamiya moves freely from the corridors of one person’s skull to the next, exploiting the koban cop’s resentment for his by-the-book partner next. A strange calm passes over the cop before he shoots his partner in the back of the head like it’s just another mundane task to be performed after taking out the trash. “He was someone I didn’t like,” the cop confesses to Takabe. “I put up with him all the time. Finally, I couldn’t stand it anymore. […] That’s how you get when you hate someone from the bottom of your heart.”

Like the teacher with his wife, the cop is a foil for Takabe, who may or may not dispatch his forensic psychologist friend, Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), by the end of the movie. When you’re alert to the microaggressions of each scene, you can also see how Mamiya’s next victim, the doctor, internalizes the sexism she deals with on a daily basis. Notice the way she gives a brief, pensive look out the window when she sits down to write after she tells her patient to take his pants down and he says, “You’re not shy, are you?”

Mamiya needles the doctor about how she wanted to be a surgeon but settled for being a general practitioner in a man’s world. Cut to her peeling a man’s face off on the floor of a public restroom. Before that, as Mamiya uses tap water to aid his hypnosis of her, he tells her, “All the things that used to be inside me, now they’re all outside.” He also says, “The inside of me is empty.” Karappo. The liberating thought of, “Why hold it in?” gives way to a sociopath, devoid of memories or feeling, shuffling down the hall in his hospital slippers, ready to treat another patient.

Takabe vs. Mamiya for the fate of the world

As Cure takes on more mysterious, occult shadings, there’s ample talk of “Mesmer,” the original German mesmerist, whose theory of animal magnetism might have something to do with that sacrificial monkey Takabe finds twisted all out of shape in a grimy bathtub. This is right around the time that Kurosawa’s film gets funky with the editing, employing quick cuts that throw the audience off since it’s already settled into the slow-burn trance of long takes and a pervasive quietude. The effect of sharing a POV character’s psychological break at a pivotal narrative moment is especially unsettling when you’ve got the lights turned down and are fully absorbed in the mood of Cure. If tone poems could kill (without being boring), this would be one.

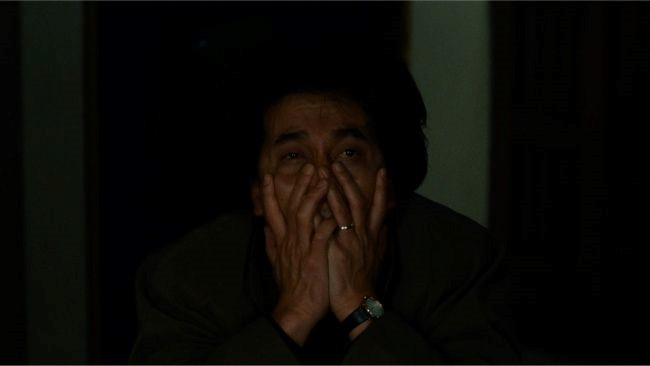

In Takabe, Mamiya may have finally met his match, someone who can take over from him as the carrier of the titular “cure” in the 21st century. At one point, they get into a hypnotic staring contest, as Takabe uses Mamiya’s own lighter against him, fighting fire with fire while the room darkens. Even after the ceiling leaks rainwater and Mamiya equates emptiness with happiness in dulcet tones, Takabe is able to resist his soothing voice. Or is he?

“We should all relax, enjoy ourselves, lead peaceful lives, but society isn’t like that,” Takabe laments. “Lunatics like you have it easy while citizens like me go through hell.” In the process of telling Mamiya (and himself) this, Takabe leaves himself open to Mamiya’s malign influence, doing the bad guy’s work for him in their increasingly shared mindscape. If the way of the sane individual is such hell, the temptation for Takabe is to abandon his duties and give himself over to a stress-free life, where Fumie is dead and the good in him is gone, but so is the guilt. Observing how he keeps his personal and professional lives compartmentalized, Mamiya asks him, “The detective or the husband, which is the real you? Neither one is the real you. There is no real you. Your wife knows that, too.”

These lines are interspersed with Takabe telling Mamiya to shut up and attempting to interject questions, which Mamiya ignores since he’s too busy interrogating his interrogator’s very sense of self. It’s a trick he pulls with one of Takabe’s superiors at police headquarters, too, asking him, “Who are you? Do you understand my question?”

Ultimately, Takabe releases all his pent-up aggression and admits, “My wife is a burden.” He’s been taught to show no emotion, whereas Mamiya wants him to uncork the bottle and pour his emotion out all over the world.

Missionary of evil

The original working title of Cure in Japanese was Dendoshi, meaning “Missionary” or “Evangelist.” At the 2018 Tokyo International Film Festival, Kurosawa indicated that it was changed at the behest of the production company, Daiei Film, to avoid any religious connotation. The Tokyo subway sarin attack, perpetrated by the real-world doomsday cult, Aum Shinrikyo, in 1995, was still recent in memory. For a mostly nonreligious country (over 70% in one recent survey, via the Associated Press), a cultish-sounding horror film might have served as an unwelcome reminder.

Daiei Film is now called Kadokawa Daiei Studio, and it’s within walking distance of my local movie theater in Chofu, Tokyo. In the train station and on the side of the studio building, you can see murals of Gamera, the Giant Monster. The monster in Cure lacks Gamera’s kaiju turtle tusks, but when he comes out of his shell, he’s no less a threat to human civilization. This goes back to something Yakusho said at the film festival about how Cure is “a movie about a human monster with no stress.”

You can still see traces of the Dendoshi angle in Cure, though that label doesn’t necessarily apply to Takabe himself until the end. Mamiya is the one who lays his hand on the doctor’s head like a prophet of doom, baptizing a new apostle. In a hypnotic trance, Sakuma, whose name rhymes with akuma (“devil”), describes Mamiya as, “A missionary. Sent to propagate the ceremony.” He speaks further of hypnotism, and how it was once thought of as “soul conjuring” in Japan, as if hypnotists themselves were mediums channeling spirits.

In Western religious terms, you could say that Mamiya is like John the Baptist if his mission was to awaken the latent evil in a sleeper demon who would become the Antichrist. In this way, he converts Takabe to the church of evil. Early on, Sakuma argues, “Even if you manage to hypnotize someone, you can’t change their basic moral sense. A person who thinks murder is evil won’t kill anyone under hypnotic suggestion.” This presupposes that people aren’t capable of having a dual nature where one side of them desires, consciously or unconsciously, to do what the other side of them considers wrong.

At the festival, speaking in Japanese, Kurosawa pinpointed Yakusho’s inscrutable quality as an actor—his ability to toggle between good and evil, even in a single scene—as the exact essence of Takabe, the protagonist who guides the audience into michi no ryōiki (unknown territory) in Cure. He and Yakusho used the word, michi, a lot, and it’s one that also pops up famously in Michi tono sôgû, or “Encounters with the Unknown,” the Japanese title of Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Takabe finds himself in a liminal space like that, encountering the unknown, crossing over into Mamiya’s territory, at the end of Cure. When he takes a bus through the clouds and meets Mamiya in an abandoned warehouse of the mind, the missionary makes his thoughts on morality and basic human indecency clear, telling Takabe, “Anyone who wants to meet his true self is bound to come here.”

Horror without borders

In Cure, what’s true for Mamiya is unconscious impulses. Inducing murder by mesmerism, he provides a pill for stress relief that comes at the cost of one’s humanity. It’s a momentary relief that, for most victims, leads to permanent anguish. Takabe is the one who breaks the mold in the cold living nightmare that is this movie. He’s the one who shows no remorse and, in fact, has a healthy appetite once the ceremony of evil is propagated. The detective, husband, and law-abiding citizen now embraces his sociopathic side, which was maybe always there, lingering under the surface, enabling him to think like the killers he’d occasionally catch hiding naked in the walls. The murder alphabet, which was up to “X” by Mamiya’s time, ends with Takabe and “Z,” which he traces on a dewy car window, and which is slashed through the movie screen as the closing credits roll.

The bloodshot eyes of this American expat first discovered Cure circa October 2015 when it screened as part of an overnight, four-movie marathon called “Masters of J-Horror” at the Tokyo International Film Festival. Back then, I would have told you the title was a nod to people’s id being unleashed as a cure for repression in Japanese culture. That may still be true on one level, but now, my earlier perspective seems limited, while Cure seems bigger and scarier, as if it’s Horror Without Borders.

The film’s relevance begins in the specific milieu where it was made, but you can’t reduce it to one culture or cathedral of art because the themes are universal. If there’s one thing crime and politics stateside have shown since 2016, it’s that some forms of repression or simple restraint definitely are preferable, like not sending that hate tweet, not joining that tiki-torch-wielding street mob, not committing that random act of violence against an Asian-American. These read like symptoms of some uncured malady in a world with a fever that’s yet to break, a fever that may be getting actively worse. Mental illness is one thing; lacking self-control or even self-awareness, like the id-programmed killers in Cure, is another.

In 2024, the first three days of Japan’s biggest family holiday, New Year’s, were marked by an inauspicious series of disasters: a major earthquake, an airport runway collision, a burning restaurant district, and a train-stabbing incident. Cure feels plucked from the tension of headlines like those, though it’s as if Mamiya’s metaphorical sickness has now spread from humanity and its petty violence to the environment and planetary catastrophes.

With wars and rumors of wars in the news globally every day, and a dreaded U.S. election rematch coming in November, the Year of the Dragon already feels positively preapocalyptic in a mid-to-late ‘90s sort of way. Tokyo wasn’t the only place with a doomsday cult taking lives before Y2K, either. When Cure was released in 1997, it was only nine months removed from the mass suicide committed by 39 members of the Heaven’s Gate cult, who hoped to catch a ride on the Hale-Bopp comet from their ranch in the San Diego suburbs.

The true horror in Cure is that of the new insanity, which is really the old insanity, cycling back around to destroy another community or civilization. It’s the horror of society breaking down, with hypnotized civilians casting off polite pretense and social conscience to act on their worst impulses. If the only cure for stress is to numb yourself to empathy, what hope do any of us have?

Categorized:Editorials