‘Goodnight Mommy’ and the Horror of Motherly Sacrifice [Matriarchy Rising]

Few tropes in horror are as controversial as that of the evil mother. From Margaret White to Annie Graham, there’s something so horrific about a mother who would turn against her young. These characters are often a perversion of an archetype near and dear to our hearts. The mother is a symbol of kindness, compassion, nurturing, and above all, selflessness. She is expected to sacrifice herself to strengthen her child. Mothers who give birth see their bodies stretch and change according to the needs of the tiny stranger growing inside their wombs. The act of birth is a body horror story in itself often involving ripping flesh, deep lacerations, and … well let’s not go into the logistical horrors of c-sections.

Rather than rest and recover in the aftermath, new mothers must care for a tiny new human literally producing food from their bodies to help the baby grow. Many mothers willingly make this sacrifice and would even count it as one of the most joyful times in their lives, but there’s no doubt that the act of mothering can be brutally taxing for the mother.

In reality, there are as many different ways to be a mother as stars in the sky. One does not need to physically produce a child or even have female biology to fill the role of mother in a person’s life. But the throughline in any motherly role is the idea of feminine sacrifice. Mothers are supposed to care for their children more than they care for themselves. They are supposed to willingly give of themselves until nothing remains, even sacrificing their own bodies for the life and well-being of their young.

The fact that we do not expect the same from fathers is both a frustrating double standard and an entire column on its own. Despite the fact that every mother is different, the mothers in our stories must fit into an extremely narrow mold. They must love and give until nothing else remains. If they do not, we turn them into monsters. Goodnight Mommy (2014), the Austrian film by writers and directors Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz plays with this monstrosity. This brutal and heartbreaking film depicts a mother violently rejected by her child as punishment for choosing to care for herself.

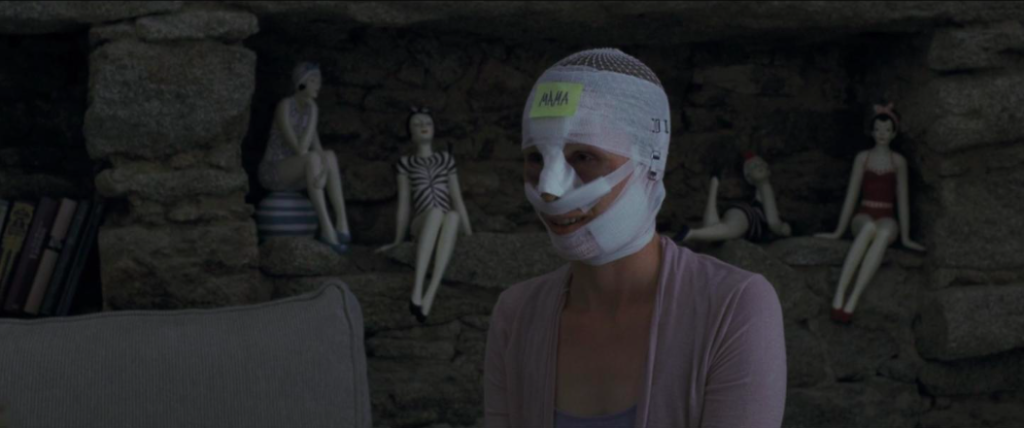

In Goodnight Mommy, Lukas (Lukas Schwarz) and Elias (Elias Schwarz) are the twin sons of a minor Austrian celebrity known only as Mutter (Susanne Wuest). Living in a gorgeous but isolated home in the countryside, they spend their days playing in the nearby fields, forests, and ponds. When a car pulls up to the house, they race inside to reunite with their mother who’s just undergone facial surgery. Her head is covered in bandages and she needs strict quiet and darkness as she recovers.

Frightened and unable to see her face, the boys immediately suspect that a more sinister transformation has occurred. They convince themselves that she is an imposter, perhaps not even human, and begin to torture her in order to find their real mother. When she cannot give them the answers they demand, they exact brutal revenge, destroying her newly constructed face and burning her alive for refusing to play along with their distorted version of the truth.

We first meet the mother wrapped in bandages shortly after her surgery. We see her before the procedure only in pictures and never learn the cause of her decision to go under the knife. With the boy’s father no longer in the picture, it’s implied that she’s attempting to find love again and this procedure is an attempt to revitalize her appearance. Known only as Mother in the film, she is perhaps hoping to reclaim some of the autonomous humanity she gave up when raising young twin sons. We never get a justification for her choice to have surgery and we don’t need one. It’s her body and she can do with it what she chooses.

But her sons are not pleased. They now see her as a stranger, rejecting the idea that she would want to be anything other than their mother. The boys want her to continue looking and acting like the nurturing woman who’s comforted them since birth. They want her to remain what she is to them, a constant caregiver and self-sacrificing figure, not a woman who would dare to indulge her own needs and desires ahead of theirs.

When Mother returns, the boys are given strict guidelines in order to help her recover. She’s not asking for much, only quiet in the house, no visitors, closed blinds, and no creatures brought in from outside. With a massive yard and extensive neighboring lands surrounding the property, they have plenty of space to play without disturbing her. But they balk at these restrictions and break them almost immediately, shocked that their mother would ask them to change their behavior for her own needs.

One of the creatures they bring into the house is a dying cat. When exploring an old crypt in a nearby village, they find the elderly creature huddled in a dark corner likely waiting to die. They bring the animal into their own home, disturbing its rest for their own amusement. The boys probably think they are helping the dying animal. But in removing it from its chosen resting place, they put their own idea of compassion and curiosity above its autonomy. In a direct parallel to their mother’s recovery, the animal has removed itself from the world, choosing solitude over an interactive life in which it might be asked to care for others.

As children, it’s natural for Elias and Lukas to think of their own needs ahead of anyone else. Part of human development is learning to care for ourselves, then learning to negotiate our needs with the circumstances of our environment. We slowly learn that we are not the center of the universe and that we won’t always get everything we want. It’s understandable for Lukas and Elias to have trouble understanding their mother’s choices.

But at nine years old, they have lived long enough to know that they must sometimes make sacrifices for other people. They are also twins and have spent their lives sharing the attention of caregivers and learning to balance their own desires against those of their brother’s. The boys should be able to understand and accept their mother’s needs. They simply refuse to, shocked that she would ask them to sacrifice their comfort for her in the same way she’s always sacrificed for them.

As Goodnight Mommy unfolds, we notice that the mother does not acknowledge Lukas, only speaking to and interacting with Elias. What at first seems cruel and abusive, eventually leads to a devastating discovery: Lukas is dead.

We never learn exactly what happened, only that it was a tragic accident and Elias feels responsible. He is coping with the loss of his twin brother with denial, imagining him around at all times and interacting with him as if he’s in the room. Viewing the story through Elias’s lens, we’ve accepted him as a living part of the story as well. Elias’ actions suddenly take on new meaning as we realize he’s been forcing his mother to share in his delusion, preparing food for her dead son and talking to him as if he is still there. She’s been playing along hoping that Elias would eventually accept the fact of his death, but she can pretend no longer.

As devastating as Lukas’s death must have been for his brother, it would be equally heartbreaking for her as well. How long must she be expected to delay her own grief for the sake of her son? But Elias can see none of this and makes her suffering worse by refusing to let her grive for her own child, compounding her pain each time he asks her to pretend he’s still.

The final act of Goodnight Mommy contains a brutal sequence in which Elias demands she confess to being an imposter. Using the bandages she’s been given to aid in her recovery, he binds her to the bed and torments her until she tells him where his real mother is. When she of course cannot, he tortures her by dousing her with water, burning her cheek with a magnifying glass, and cutting her lips and mouth.

While upsetting, his actions are even more insidious because every act of brutality is directed at her face, the sight of her recent surgery. Goaded by a vision of Lukas, Elias destroys not only the painful work she’s just had done, but the face she’s kept hidden from him in what feels like an effort to erase her transgression. He demands she return to the mother he knew, the mother who exists only to serve him, the mother who bases her appearance on his needs and comfort rather than her own.

When Mother finally escapes from the bed, she trips and is knocked unconscious while running for the door. She awakens to find herself glued to the living room floor surrounded by lit candles and a burning tank full of chemicals and the floating body of the dead cat. Elias stands above her and insists she see her dead son in a shared delusion. Elias asks for her to tell him what Lukas (holding a lit candle to a curtain) is doing now. When she can’t share his hallucination, he sets fire to the drapes lighting the room with rapidly spreading flames. He views her failure to see him as proof that she is not his mother and does not love him enough to help him reject reality. “Our mother would know,” he says, dismissing her parentage because of an arbitrary fact he’s chosen to invalidate her love.

He seemingly feels no guilt for what can only be described as murder, viewing it as an act necessary to saving his mother. This is likely what he tells himself, but what he is really doing is rejecting her care because it comes with the acceptance of his role in his brother’s death. If he can pretend she’s not really his mother, he can go on pretending Lukas is still alive. To accept her love means losing his last remaining connection to his twin brother.

Goodnight Mommy concludes as Elias and Lukas watch their mother writhing in agony on the floor of their home. She is swept up in the fire and dies screaming her remaining son’s name. The three are reunited in the fields outside and watch as the house crumbles in flames. We don’t know if Elias has survived, but we do know he’s gotten what he wanted: the return of his loving family and the erasure of the tragedies he’s tried so hard to reject. They succumbed to Elias’s refusal to move on from the death of his brother.

What makes Goodnight Mommy so powerful is its indictment of the Evil Mother archetype. With all cards on the table, we can see that she is not the villain of the story. She is simply a woman trying to move on with her life after a devastating tragedy. It’s only when viewing the story through Elias’s eyes that her actions seem evil. He refuses to see her as an individual person, only an avatar for his own care and love. Her refusal to give him what he needs regardless of the cost to her own life, transforms her into a monster. When she tries to embrace her own humanity, he rejects her.

While extreme, the mother’s story in Goodnight Mommy is not so different from what many women and people who can get pregnant are experiencing today. With the overturn of Roe v. Wade and a wave of abortion bans across the US, women’s bodies are being treated like inhuman vessels for children and sacrificial flesh for evangelical conviction. We are expected to sacrifice our own lives, bodies, and happiness for cells that grow in our wombs. And if we reject this sacrifice, we’re called murderers.

The mother is vilified until the final act for simply trying to move on with her life. She wants to find happiness of her own while still caring for her son. The mother is not the monster in Goodnight Mommy. The true villain is Elias and his refusal to allow his mother the autonomy he demands for himself. His inability to see her as a human being in her own right ends up causing the destruction of them both.

Categorized:Editorials Matriarchy Rising News