Philip J Reed’s ‘The Wolf Man’ and Me [DieDieBooks Review]

I tried to die by suicide once. For readers of this site, that might not come as much of a surprise because I’ve written about it at least twice, maybe more. It was the springboard for my piece on I’m Thinking of Ending Things and the contextual wraparound for an editorial revisiting Final Destination 2. In fairness, there’s a good chance those pieces blipped by. It’s more regularly my news pieces that attract readers to my inbox, thanking or denigrating me in equal measure for recommending the best or worst movie they’ve ever seen. I mention that because it would be very hard to speculate about who I am, the full scope of my life and personhood, from my writing alone.

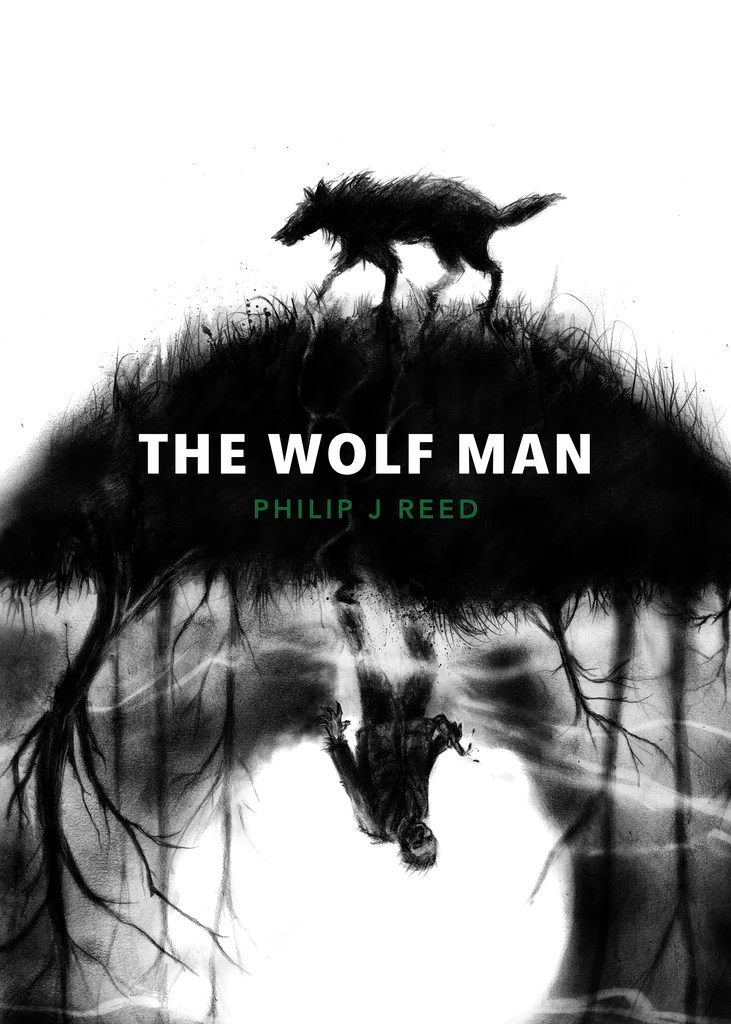

I have a newsletter with five subscribers and two wonderful editors here. They’d be better equipped than most, but ultimately, it’d simply be a shadow of who I was, a refraction within my total control to shape and morph as I please. It would, in other words, be a narrative that fell under my jurisdiction—my story, the way I wanted it to be seen. This brings us to Philip J Reed’s The Wolf Man, the third release in the DieDieBooks series.

Also Read: ‘In a Violent Nature’ Sundance 2024 Review: Ripping Up the Slasher and Showing Its Guts

Full stop, the series has been phenomenal, singular accounts of well-known horror texts filtered through a lens equal part academic and human. Bob Mielke’s Threads, the first release in the series, was conspicuously, compellingly political. Philip Trussell’s Poltergeist was no less a marvel, a book-length essay that found the human core of Poltergeist, Tobe Hooper, and gave him his long-awaited due. I wonder if that might be a reviewer’s job, to reduce complex work into a single, conceptual notion. Threads was politics and Poltergeist was people. The DieDieBooks releases are, in fairness, simply titled after the movies themselves, centering the fiction at first glance. It’s the periphery that matters, and maybe that’s the point. That is, after all, where both Mielke and Trussell cultivate profound, often moving insights into media texts audiences likely think they know well.

If that is the reviewer’s job, then Reed’s The Wolf Man poses a bigger problem than most. Not because it isn’t good. It is. In fact, I’d go so far as to call it a masterpiece, accountable for one of the most visceral, moving reactions I’ve had to a piece of writing in some time. It’s not my intention to tease what I, and readers, might likely know as some kind of big reveal, so I’ll simply say it here. Author Philip J Reed died by suicide on July 30, 2022. The back cover simply says he passed away. It’s not until the Afterword that I was aware of the circumstances surrounding Reed’s passing.

Also Read: ‘Dario Argento Panico’ Review: A Riveting Profile of a Legendary Creator

Editor Nick Toti, grappling with what must have been a heartbreakingly difficult task, pens an ode to both Reed, his work, and his legacy through what little insight he had. “The circumstances of Philip’s life, whatever they were, gave him the tools to write a book on The Wolf Man that had more insight, and was more deeply felt, than anyone could have expected,” he notes in the Afterword, simultaneously accounting for some mistakes that crept their way into the draft he worked from. Reed didn’t get everything right, though Toti remains convinced—as do I—that the factual inaccuracy of some claims does little to erode the integrity of his insights, the meaning—however small—he culled from an Old Hollywood tragedy.

Reed opens with an introduction recounting his first exposure to George Waggner’s 1941 classic. He, like myself, was a purveyor of ostensibly bad cinema. Not to denigrate or trash it, but to find the pulsating heart within. Bad things come from good people with good hearts, and for those of us willing to look, it’s not often hard to find. Granted, The Wolf Man isn’t a bad movie, and that principally accounts for Reed’s interest in the text. Here he thought he was going to watch some late-night schlock. Instead, like my own experience reading his book on the matter, he found a bit of himself.

Also Read: ‘I.S.S.’ Review: Claustrophobia And Tension Abound In New Space Thriller

From there, Reed focuses on performer Creighton Chaney (stage name Lon Chaney Jr.), letting the history of The Wolf Man, of the Universal Monsters, and of Chaney’s father, Lon Chaney, orbit around this one man, this one performance. It might sound overstuffed, but there is a propulsive emotional throughline, often chronological, sketching three distinct versions of Chaney throughout his life: the person he was, the character he played, and the person he so desperately wished to be.

I’d watched the movie for the first time when I was contacted for this review. My horror blind spots are arbitrary, though The Wolf Man had found its way there (the 2010 remake is a different story). I was pleased to see my initial reaction paralleled Reed’s. I thought it was going to be good, but I didn’t anticipate it was going to be great. It was. Maybe not great enough to be my favorite of the Universal Monsters, but great enough to impact me, to imbue Reed’s writing with that extra edge of resonance and empathy. I could see what he was saying. Sometimes, I could see it before maybe even Reed saw it himself.

It is not my intent to center myself in this review. In The Wolf Man, it’s also not Reed’s intent to center himself. But he does, and that, truly, is both is greatest success and most stinging heartbreak. Writing on Chaney—“Chaney was many things at many times. We can focus on the Wolf. We can focus on the Man. But they’re both there”—is an evocation of Reed, a transcript of his story in someone else’s.

Also Read: ‘Presence’ Sundance 2024 Review: A Technically Stunning Haunted House

Creighton Chaney remains there at the core. Reed is too talented a writer to let his subtext diminish his subject. The Wolf Man is part history, part speculation. The broad terms we know are that Chaney did not have an easy life, and he did not care much for his father. In the Afterword, Toti challenges Reed’s core claim that Lon Chaney (Sr.) was as abusive toward his son as Reed contends. IMDB is not gospel, though even there, one of the top notes on Chaney’s page accounts for how dedicated a father he was. Those lived experiences can be tough to verify, especially among two men, both Creighton and his father, who lived close to themselves, kept their truths cloistered, allowing them only to spill out every so often. They left fractured pieces—audiences had to put them together.

It is clear that some part of Creighton died long before he began work on The Wolf Man. I agree with Reed that it is a very good, yet unintentional, performance. Creighton is talented, no doubt, though entire arcs play differently, not on account of the script or the blocking, and not even on account of Chaney’s voice, but simply his presence, his proximity to those around him. The fact that he is there at all changes what The Wolf Man is. Reed notes, “The very human moments that the film managed to capture are every bit as relatable and insightful as they ever were, and every one of them comes courtesy of Chaney.”

Also Read: ‘I Saw the TV Glow’ Sundance 2024 Review: A Masterpiece

Chaney’s life was one marred by tragedy, even if the full extent is unknown. He had errant parents in show business. He was often poor, just barely scraping by. Later in life, those worst parts of his childhood manifested within him. He was an alcoholic, regularly abusive, and innately incapable of allowing any success of his to endure. It’s painful to track Chaney’s wins and inevitable failures. He couldn’t allow himself to have much of a good thing for very long. What hurts more is knowing exactly what that’s like. Whether it’s a father, a culture, or an industry, the lies they tell start to feel like truths, like fates. You don’t deserve happiness, and when you get it, make sure it doesn’t last.

Interspersed throughout are deep readings of The Wolf Man itself, scene-by-scene breakdowns that give supporting players and writers their due, connecting them to the larger schema of Chaney’s life and the way he interpreted the world. Conventionally for the time, the cast and crew of The Wolf Man didn’t just know Chaney from that project. Its success, and the innate nature of the Hollywood system at the time, meant they’d regularly be working together again on some other project, some other gamble.

Chaney and The Wolf Man writer Curt Siodmak, for instance, would collaborate several times in the years after release before the life Chaney had been consigned to live caught up with him. Reed writes, “[Universal] cast Chaney in more than 25 productions between The Wolf Man and the end of 1945. They gave him opportunity after opportunity to pull himself together/Universal hired a desperate Man and fired an uncontrollable Wolf.”

Also Read: ‘Love Lies Bleeding’ Sundance 2024 Review: Romance and Gore

Creighton Chaney would die of cardiac failure in 1973. He’d tried to die by suicide himself once before, mirroring his mother who had tried the same some 50 years before. It’s a visceral transition, moving from the end of Chaney’s life to the end of Reed’s, though it conceptualizes the full breadth of what Reed accomplished here. His final words: “It’s a tragic end for Chaney, but we can focus on the related, more positive fact that his tragedy came to an end. Yes. Let’s focus on that. The movie ended that way for a reason.”

Some part of Chaney died long before he actually did. I won’t speculate whether the same was true for Reed, but I know it was true for me. I grieved myself, a person that I never was and convinced I never would be. There was a tragedy inside me I didn’t think could ever be fixed. I was all on my own. And I was scared. More scared than I’d ever been before.

I didn’t know Philip, but I felt the same kind of subliminal kinship toward him that he felt toward Chaney. I am grateful to have read his words and I am grateful to have read his story. It moved me beyond comprehension. And while it broke my heart, the best thing I think I can do is focus on the ways it affirmed me, affirmed Philip’s singular ability to make meaning in this world. It mattered to me. I hope it will matter to you when you pick up this book. I want to focus on that.

You can purchase a copy of Philip J. Reed’s The Wolf Man here.

Categorized:Reviews