DieDieBook’s Latest Is A Fascinating Look At The Troubled History of ‘Poltergeist’ [Review]

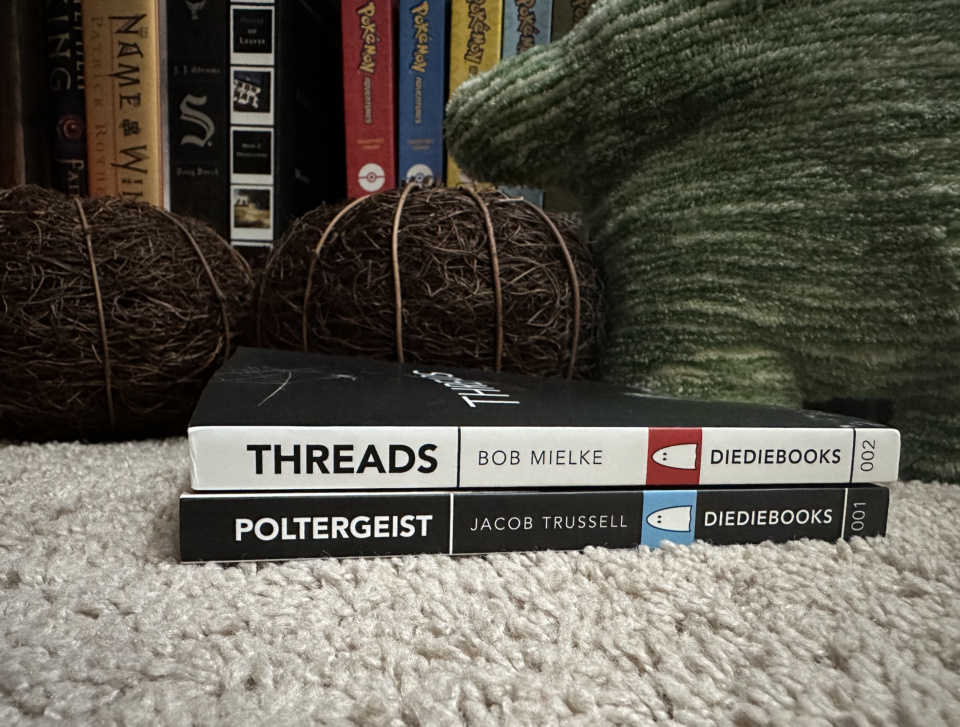

A book about Poltergeist, the 1982 haunted house movie to end all haunted house movies, could take as many shapes as its titular spectral force. A haunted clown, a possessed tree—an academic interrogation of Poltergeist’s legacy and mythos, or perhaps more compellingly, an empathetic foray into the longstanding tension between Steven Spielberg and Tobe Hooper over authorship. Like Bob Mielke’s Threads, publisher DieDieBooks’ latest book-length horror essay (for now), Jacob Trussell’s Poltergeist is a marvel. This is auteur theory as fellowship, a deeply human and stunningly well-researched account of Poltergeist’s origins and the development of Tobe Hooper’s directorial status into Hollywood myth.

Like the oft-cited Poltergeist curse at the movie’s core (an urban legend Trussell wisely puts to rest toward the end), whether Tobe Hooper or Steven Spielberg directed Poltergeist remains a point of contention among not just horror fans, but moviegoers in general. It’s cinephile rubbernecking at an ostensible feud that has spanned decades, one so abounding with misinformation, audiences might reasonably believe neither directed the picture—it might well have been reanimated skeletons behind the camera all along.

Trussell opens with a deluge of internet comments (painful for anyone whose work has been published online before) deliberating the matter of Poltergeist’s ownership, insightfully appending his own context to the perennial debate: “People come to feel like it’s their civic duty to defend someone they love, but will never know, by waging flame wars on social media, message boards, and website comments sections.”

Authorship of Poltergeist isn’t just a matter of cinematic identity—it’s indicative of a moviegoer’s singular, value-based identity. Like Spielberg’s The Fabelmans, his most recent directorial outing, cinema is identity—it’s cinema that both makes and breaks us.

I won’t treat Trussell’s conclusion as a sordid final act. There are no closet gateways or pools of the dead. Reasonably (and intelligently, given the considerable material Trussell culled and reviewed, ranging from contemporaneous quotes to behind-the-scenes perspectives), Poltergeist the book concludes that Poltergeist the movie, from its origins as Night Skies, a sequel to Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, was a collaborative effort. It bears the thematic and stylistic marks of both Hooper and Spielberg, though unequivocally, it was Hooper’s to direct.

Trussell wisely contextualizes the early lives of both filmmakers and their diverging paths into filmmaking. While more common with Spielberg, both regularly revised their own biographies, scaffolding the myths of their own lives the way creatives of all slices are wont to do. Early in his career, Spielberg yielded both power and fragility, and that noxious combination was principally responsible for the enduring yet unfounded myth that he secretly directed Poltergeist, with Hooper being nothing more than a symbolic figurehead.

It isn’t true, though it’s easy by dint of Trussell’s immaculate research to see how it came to be. Yet, beyond the systemic account of Poltergeist’s production, release, and authorship litigation, Poltergeist is most successful as an ode to Hooper himself. Trussell notes toward the end,

“This gets to the heart of what the authorship debate should be focused on: the erasure of Hooper’s creative contribution to Poltergeist. The critics of Hooper’s work seem to deliberately forget that he was a visionary filmmaker with a proven track record of creating ravishing works of effective horror. Yes, he was a non-confrontational director, at odds with Spielberg’s explosive on-set personality, but that says nothing to the artistry and creative vision he brought to every movie he made, including Poltergeist.”

The authorship debate is both Hollywood myth and a denigration of one of the genre’s greatest. Opening with the aforementioned tweets, Trussell maintains a consistent thematic throughline of empathy for Poltergeist’s entirety. Like the similarly recurrent Poltergeist curse, audiences and critics too regularly forget that the works they enjoy have their origins in other people. Creatives like Hooper are no more or less immune to the trials, traumas, and pains of daily life. Their lived experiences, though remarkable, are not distinctly inoculated from hurt. In debating Poltergeist, Trussell argues, audiences are really debating Hooper’s intrinsic value as both a filmmaker and, more broadly, a person.

A poignant concluding note reads, “Hooper may have known that the American Dream was hollow, but he never could have anticipated quite how unfulfilling its promises would be for him.” Hooper remains a keystone contributor to not just the horror genre, but independent filmmaking writ large as we know it today. Debate the merit of his work all you want, but to fundamentally deny him ownership of what should have been his big break is more than disingenuous—it’s cruel.

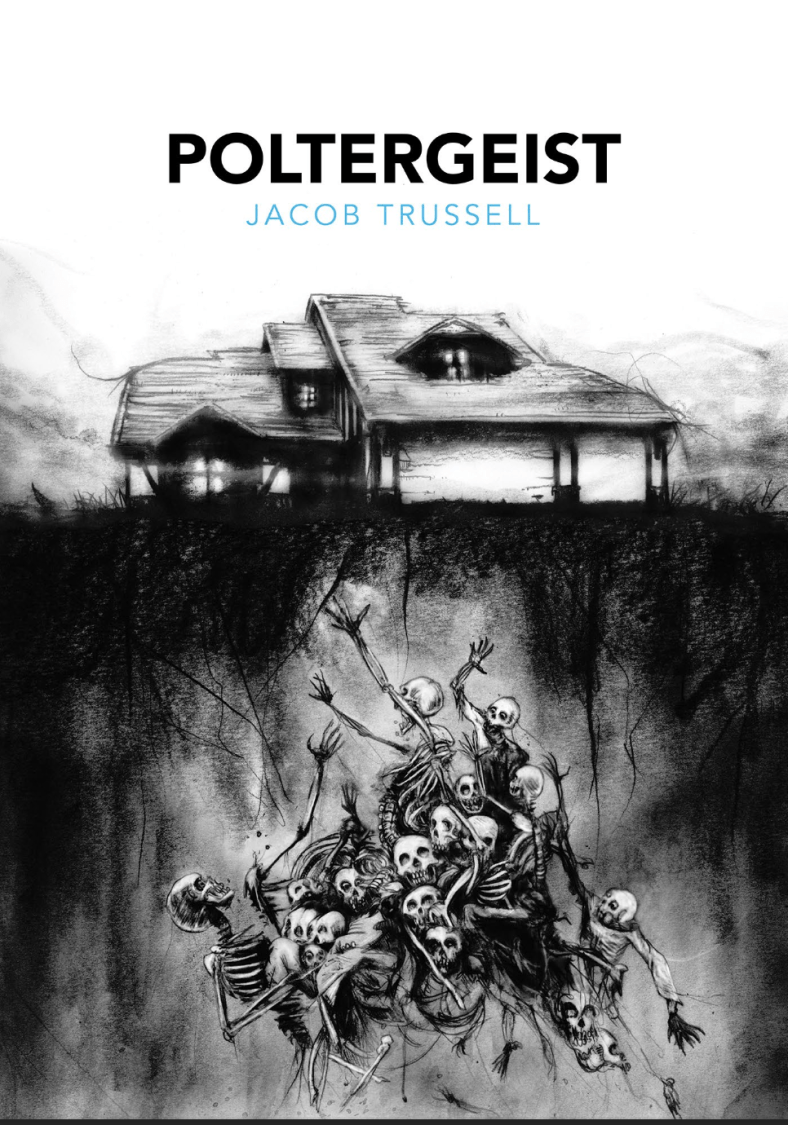

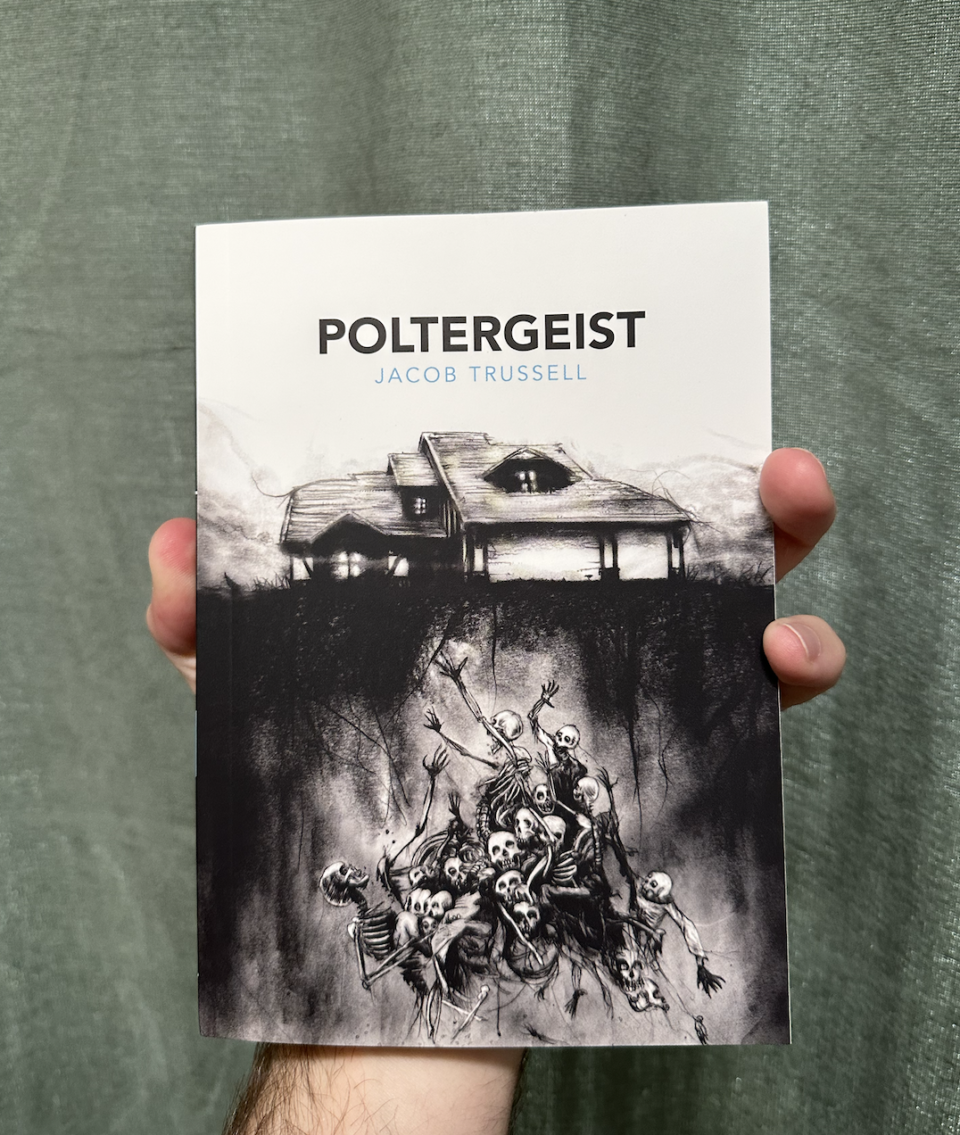

Like previous DieDieBooks release Threads, Poltergeist warrants purchase. Trussell’s humanism and sharp wit are evident on every page, and Andy Sciazko’s cover art (you can view his portfolio here) is phenomenally gothic. With two releases thus far, DieDieBooks is at the forefront of new, deeply felt film criticism. With diverse voices and stunning research, I cannot wait to see what they do next.

You can purchase your copy of Jacob Trussell’s Poltergeist here!

Categorized:Reviews