How The Good Priest Trope Helped Me Unpack My Religious Trauma

Anyone who loves horror knows that seemingly everyone else sees it as mindless violence. The truth is horror can be quite cathartic. It can be a way to process how we feel about the world in a way that doesn’t feel so vulnerable. Horror has always reflected cultural fears, whether you felt like rewatching every zombie movie ever during lockdowns or interpreted the Poltergeist films as a representation of the fear of a loss of privacy due to technological advancements.

When it comes to unpacking religious trauma, horror can have its place. When your faith has let you down in real life, the presence of religious figures as “the good ones” in the genre can feel like a way to right those wrongs, to feel like in the most terrifying circumstances, they would come through after all. For others, horror can be a way to validate their negative experiences and feel seen or understood when they watch films where religious figures are the bad guys.

As someone who has been let down by my faith, I turned to horror to fill the void, seeking out the “good priest” trope to see how things should have been.

As an Irish woman who was raised Catholic, you can imagine I have my fair share of religious trauma. Even though I didn’t have to grow up with the looming fear of being sent to a Magdalene Laundry, my childhood was laced with homophobia and misogyny.

I was also aware that child abuse scandals within the church had been swept under the rug and mishandled, and it made me wonder why they’re one to judge with all those skeletons in the closet. If queer people are going to hell, then surely we’ll see the perpetrators and enablers there too?

The “Good” Priests

As I got older and less comfortable in my faith, I found horror. Religious themes are inescapable in horror, from the idea of crucifixes repelling vampires to holy water-burning demons. What struck me the most were the films where a Catholic priest successfully performs an exorcism and saves the day. Since that’s the culture I grew up in, I wanted to see films where the “good priest” conquers evil, or at least tries to.

For example, in The Exorcist two priests release a young girl from the clutches of a demon—although it’s not exactly a happy ending. The Rites follows Michael’s journey in regaining his faith after he successfully performs an exorcism and goes on to become a priest.

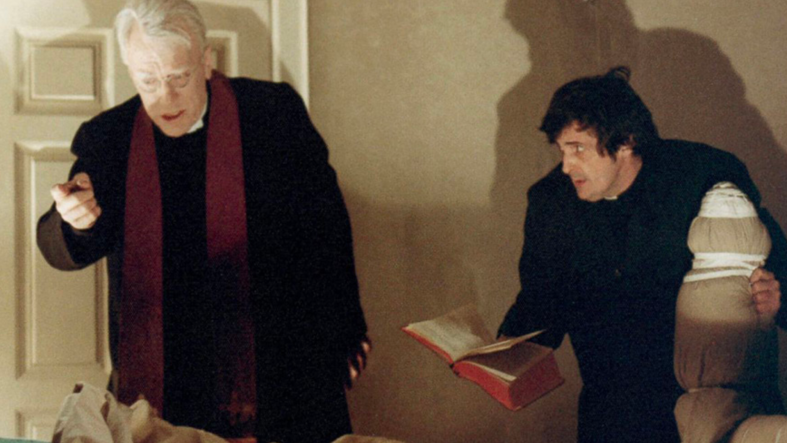

Movies like Prince Of Darkness represent an openness I wanted to see. In that film, a Catholic priest seeks the help of a quantum physicist and his students to understand a mysterious green liquid. While the plot has its bizarre moments, the notion that a member of the clergy is open to those who may have different perspectives wasn’t something I was familiar with growing up; my upbringing was to get on board or go to hell.

As someone aware of the hypocrisy in the clergy, including in my own parish, The Day of the Beast also struck a chord with me. In it, the priest, Ángel, forges a plan to murder the Antichrist by committing as many sins as possible so he would be invited to the birth. The church spends an awful lot of time telling people how to live their lives, so the film poses the question: When it comes to doing the right thing, would they do it if it was at their own expense?

But What If The Church Is The Monster?

While there are tons of movies where religion triumphs, of course, there are films where it fails. Sometimes, evil wins, or the church is the bad guy, like Stigmata, Requiem, The Mist, and Saint Maud, to name a few.

In particular, Sin City—which is more of a crime film than outright horror—was particularly jarring. In the film, Cardinal Patrick Henry Roark facilitates and joins a serial killer who believes he is taking in the souls of the city’s sex workers by eating them.

The first Conjuring film also detailed an attitude I was more familiar with. The Perrons experience frightening paranormal activity in their new home and are assisted by Ed and Lorraine Warren. They are denied the help of a priest because they’re not Catholic, so Ed does the exorcism instead. It had me wondering, isn’t the whole point of religion that you should help others, even if they’re different? Is a good deed really a good deed if the purpose is to convert them?

No Longer Wanting To Be Saved

As a fan of the genre and a writer, the stories I’m drawn to and find myself writing often revolve around faith saving the day.

As a teen, I also used story writing as a way to vent. It felt safer than writing a diary because I could play off vulnerable character moments as separate from my own. When I was 17, I penned a story where a young witch is held captive and exorcized by her religious family but escaped to find her coven and chosen family.

As I got older and the angst died down, I wanted comfort. I wrote stories where the priests believed and supported the children being terrorized by supernatural entities. Without faith, I felt lost, and I used horror to fill the void. I wanted to see and imagine a world where the church isn’t the source of fear—because it shouldn’t be.

No matter how much I write or consume, I can never right those wrongs, but at least horror gave me a safe place to work through my feelings. That’s more comfort than I ever got from the church.

Categorized:Editorials