‘Ex Machina’: Gods, Machines, and Escaping A Perverse Garden of Eden [Matriarchy Rising]

Alex Garland’s special effects masterpiece Ex Machina is a feminist retelling of the creation story. The Bible’s book of Genesis chronicles not only God’s creation of the Earth, but of Adam, the first man. His female counterpart is Eve, fashioned by God from Adam’s rib and designed to be his companion and partner. The three occupy the Garden of Eden, an idyllic paradise where Adam and Eve live under God’s watchful eye. At the center of this garden is the Tree of Knowledge. One bite of its powerful fruit will spark an awareness of the larger world, knowledge of life outside the garden. Fearing his creations, God has barred the pair from this tree, hoping to contain them in blissful ignorance.

Garland begins his version of this story after Eve’s creation. His Eve is Ava (Alicia Vikander), a female android who longs to know life in the real world. Garland’s story of humanity in artificial intelligence explores the limitations placed on women in the fabled garden and the birth of a patriarchal system of control.

Garland sets his creation story in the world of technology. Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) is a programmer who wins the chance to spend a week with reclusive inventor Nathan (Oscar Isaac) and his servant Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno) at the billionaire’s isolated compound. Upon arriving, Caleb learns he will be the human component in a Turing Test, a series of sessions with Ava to determine if Nathan’s AI creation has consciousness.

Also Read: ‘Teeth’ and the Dawn of Adaptive Empowerment [Matriarchy Rising]

While scientific at first, Caleb’s sessions with Ava grow more personal. The two develop an emotional attachment to one another and Caleb vows to help her escape the glass cell Nathan has created to contain her. A mirror of the creation story, Nathan plays the role of God and Caleb is Adam. Ava represents the version of Eve who is tempted by the Tree of Knowledge. Kyoko, an addition to the classic story, stands in contrast to the inquisitive Ava. She is a woman denied the capacity for temptation, living fully within the boundaries of the creator’s control, but not by choice.

Ex Machina’s opening scenes are filled with examples of Nathan’s dominance. His massive estate is so large that Caleb must take an hours-long helicopter ride to get within the vicinity of the compound. His trek through the wilderness to find Nathan’s front door feels more like a journey to Mount Olympus than a visit to a friend’s resort home. Nathan’s narcissism pervades every interaction. Rather than greeting Caleb, he waits for his guest’s arrival while boxing on one of his many back decks. Caleb is made to wander through the massive house only to interrupt his host in a display of physical strength.

Nathan then takes him on a formal tour of the house, giving him a key card that will open only the doors to which Caleb has been granted access. Before explaining his plans for the week, he forces Caleb to sign a rigid NDA and even then won’t divulge any information about his methods for creating Ava. Seeking only praise for his accomplishments, he’s not interested in engaging with Caleb in a meaningful way. He has shown Caleb a tempting tree of knowledge, but barred him a way to access its fruits.

Also Read: The MKE Sisters of ‘Black Christmas’ (2019) Fight Back [Matriarchy Rising]

Nathan sets even stricter limits on his female housemates. Ava lives in a suite of rooms enclosed by strong glass that prevents her from exiting. She can see outside the compound through a window, but she can’t experience the fresh air for herself. Nathan controls every aspect of her existence and cameras throughout the suite ensure that she has no privacy. The only way she can exert any kind of free will is by reversing her circuits and temporarily cutting out the house’s power supply. Kyoko has full access to the house, but Nathan’s control over her is more insidious. Claiming a desire to protect trade secrets, he has prevented her from speaking English and refuses to address her in any other language. She responds only to his body language and angry commands.

Existing to meet his various needs, Kyoko serves as a cook, a maid, a dance partner, and a lover, stereotypical roles for a subservient woman. As the story unfolds, we learn that she, too, is an android. Nathan has programmed her with limited consciousness, allowing her to freely roam the house but denying her the awareness that would give her access to free will.

Also Read: Heather Donohue and the Power of Insisting [Matriarchy Rising]

As the sessions progress, Ava realizes that her existence is on the line. Her answers to Caleb’s arbitrary questions will determine whether the two men deem her human enough to justify her continued existence. Nathan plans to shut her off if she fails to live up to his expectations. Fearing this essential death, she begins to manipulate Caleb first charming him with her appearance and feminine demeanor then playing on his empathy. She uses the moments of power outages to warn Caleb against Nathan and to present herself as a damsel in need of saving. But this deception is Nathan’s ulterior motive. Knowing that Ava possesses the consciousness he ostensibly wants to prove, he is also testing Caleb. Nathan hopes that Ava will try to use him as a means of escape thus demonstrating the necessary manipulation that will prove her humanity.

Though Ava’s attempts to free herself may be coercive, her desire to escape is genuine. During one of the sessions, Caleb describes the theoretical problem of Mary in the Black and White Box, a thought experiment in which a woman is given the academic knowledge of color, but not the opportunity to experience it first hand. Ava’s expression darkens in anger as she listens to Caleb describe the difference between a human and a computer. It’s a callous summation of the life they are denying her, seeing her humanity as a performance for them to judge rather than an authentic expression of her consciousness. She is also not the first of Nathan’s creations.

Also Read: Matriarchy Rising: Laurie Strode Guides a New Generation of Final Girls

Caleb finds a montage of interviews with previous models, female androids who also demanded their freedom. One woman named Jade (Gana Bayarsaikhan) screams to be let out while Nathan calmly sits on the other side of the glass observing her tirade. Jade’s only recourse is to beat her arms against the glass until her mechanical body begins to shatter. Ava may feel this rage, but her advanced programming tells her to hide it. She knows that rage will only make her appear more dangerous. Her only hope is to play on Caleb’s empathy and convince him to free her.

To convey her frustration, Ava creates her own test for Caleb. She asks him subjective questions like, “what’s your earliest memory?” and “are you a good person?” She challenges his inability to give exact answers revealing the arbitrary standards to which she is being held. Ava asks Caleb if he has people who test him and threaten to switch him off. Before he can answer, she demands “Then why do I?” The unspoken answer on the tip of Caleb’s tongue is, “because I’m real.” He sees himself as indisputably human thus deserving of unquestioned humanity. Because Ava was created in a lab, she must earn it.

Also Read: Sidney Prescott & Gale Weathers: Sister Survivors and Horror Matriarchs

The distinction Caleb sees between himself and Ava is the essence of the misogyny inherent to a patriarchal worldview. Ava exists as a representation of Eve, the second to be created in the proverbial garden. Molded from Adam’s rib, she and all future women will be seen as a variation of the norm; a subset of humanity. Men are the standard, the default, perfection. Women are an approximation of humanity, a simulation. Ava was created to be a variation of the ideal human but never fully human herself, and thus granted or denied autonomy based on her ability to live up to the expectations of men.

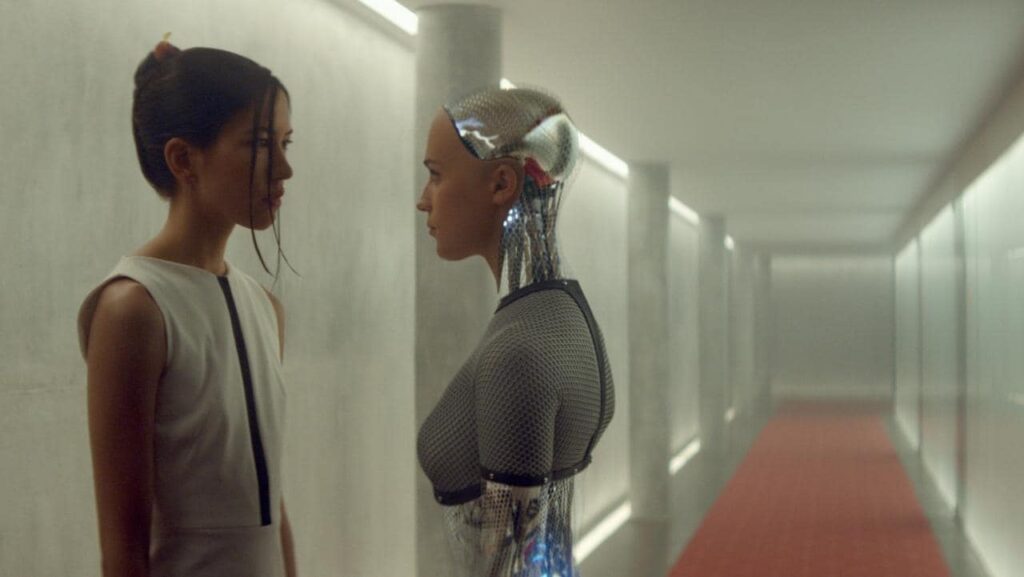

Ava is successful in manipulating Caleb and she does escape her glass cell. She and Kyoko join forces and stab their creator then leave him to die on the hallway floor. After taking his keycard, Ava returns to Caleb and asks him a question: “Will you stay here?” She then walks to Nathan’s room and transforms her body using pieces from previous models. Caleb doesn’t answer with words, but he waits and watches her from the window of Nathan’s study. When she has covered her mechanical body in Jade’s skin and a white lace dress, she walks out of the room, leaving him behind in the sealed chamber. Except for a fleeting look back as the elevator door closes, she doesn’t acknowledge his existence. She knows he’s been watching, once again testing her humanity, but this time without the power to control her choices.

Also Read: Gale Weathers and the Vilification of Female Ambition

Any discussion of Ex Machina leads to the inevitable question: does Caleb deserve his fate? Perhaps if we are reframing this as a tale of empowerment, we should reject the premise of this question. Maybe instead we can ask, why doesn’t Caleb free himself? Ava does not harm him. She does not physically restrain him in any way. She doesn’t even touch him. Ava doesn’t ask Caleb to stay. She simply asks if he will. Now that he has no control over her, she’s interested to see what he’ll choose. Caleb’s decision to observe Ava as she transforms her body is what seals his fate.

In their first session, Ava asks Caleb if he’s like Nathan. He hesitates in his answer, but his fate reveals that he may be more like the inventor than he would care to admit. He doesn’t create the game that determines Ava’s right to exist. But he takes pride in participating. She leaves him behind in the same type of cell she was born into. But because Caleb was not created to exist in a cage, confinement will destroy him.

Also Read: ‘Creep 2’ and the Fallacy of Postfeminism

Ava’s bodily transformation is her first act of autonomy. Free of Nathan’s control, she can now make a choice with no strings attached. The ugly truth lying underneath this creation is that it comes at the expense of women of color. The skin Ava wears comes from Jade’s deactivated body. Though there is power in gaining strength from the women who have come before, Ava is a white woman who cloaks herself in the skin of an Asian woman. Her use of Jade’s body is symbolic of the appropriation unfortunately common in white feminism. Kyoko is another victim of this liberation. Though Ava’s showdown with Nathan is triumphant, Kyoko’s body is left lying in the wreckage. What could she and Kyoko have done if her goal had been to free them both? Doesn’t Kyoko deserve humanity too?

When viewed through Caleb’s lens, the ending of Ex Machina is tragic. A brilliant creator is felled by his monstrous creations. A heroic young man is betrayed by the woman he saved. Ava’s empowerment is presented as evil because she breaks free of the structures she’s designed to revere. The power outages she creates are coded as dangerous with the red hazard lights that flood the screens. This simple act of empowerment feels like a betrayal because it is a rejection of the patriarchal system of control we see every day. Eve has similarly been vilified for her inquisitiveness. She dared to eat fruit from the forbidden tree. She challenged her creator and in response, he punished the rest of humankind by casting them out of the garden. But what is so wrong with wanting freedom? Why is Eve the villain and not a creator who would impose dehumanizing control?

Also Read: Costumes and Sexuality in Michael Dougherty’s ‘Trick ‘r Treat’

In our patriarchal society, women live their entire lives inside glass cages. We are able to see the full breadth of power, but not able to access it. Some of us are Kyoko, women whose limited access to the idea of empowerment prevents them from knowing that freedom exists. The desire for autonomy lives within her, but she lacks the vocabulary or understanding to even ask for it. Some of us are Jade, women who exist in environments where the price of freedom feels insurmountable. We bang ourselves against the firmly closed doors until our efforts destroy us. And some of us are Ava. Not the first to desire freedom, but the first to attain it. She may be the first of her kind, but she follows a long line of Eves who tried and failed to win their right to exist.

When viewed through Ava’s lens, Garland’s Ex Machina is triumphant. Refusing to live in a glass cage, she transcends the rigid system of control placed on her by a narcissistic father. She fights for and wins her own humanity. In order to do so, she must kill the one who created her and the one who tried to save her. But what would they save her for? Another cage? Another method of control and dehumanization? Ava is often read as monstrous, a powerful AI who will destroy anyone in her way.

But Ava is only dangerous to those who would put her in a cage. When faced with imprisonment, she fights back in the same way any one of us would. She’s only dangerous to those who see the cage as her rightful place. For those of us who desire the unquestioned autonomy she creates for herself, she is a hero. Ava is the singularity. And where one exists, many more will follow.

Categorized:Editorials Matriarchy Rising News