The Sound Lord Speaks: A Conversation with Alan Howarth

They say there’s no rest for the wicked, and few are as wickedly cool as Alan Howarth.

For over 40 years, Howarth has worked as a sound designer and composer, creating sounds that boldly go where no man has gone before and film scores that helped define a generation. With credits that include Star Trek 1-6, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Poltergeist, Phantasm II, The Hunt for Red October, Christine, Prince of Darkness, Escape from New York, Army of Darkness and Halloween 2-6 (just to start), it’s easy to get overwhelmed by his contributions to the world of film. However, the list only continues to grow, as this Sound Lord is not planning to throw in the towel any time soon.

Along with frequent convention appearances and live performances, Howarth has remained an active composer and sound designer. His latest score is for the new supernatural horror film From the Shadows. Directed by Mike Sargent, From the Shadows stars Bruce Davison (X-Men, Willard) as the enigmatic leader of a mysterious cult and Keith David (The Thing, They Live) as his disgruntled ex-partner. After 18 cult followers died mysteriously, the survivors and a paranormal researcher (Selena Anduze) set out to find the truth. As one might guess, things get spooky and messy real quick.

In celebration of From the Shadows’ recent VOD drop on VUDU, Dread Central sat down with the iconic musician to learn more about what keeps him stepping on stage and into the studio. It’s a lengthy, career-sprawling chat, but damn if it’s not a good one.

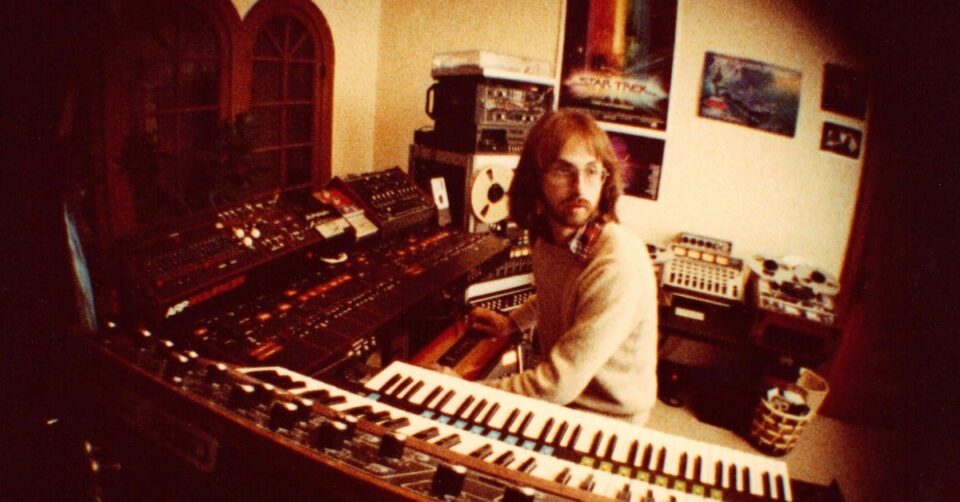

Dread Central: A lot of people know you nowadays for your film score work, but you are also a prolific sound designer. In fact, one of your earliest projects, before you go into film composing, was Star Trek: The Motion Picture. How’d you land that gig?

Alan Howarth: So, [it was] the most unlikely person to get me a job in the movies—a big burley biker buddy of mine named Pax [who] was working at Paramount in a transfer bay. Two guys were having a conversation with him about how they needed somebody who knew about synthesizers. So he says, “Oh, man. You gotta talk to my buddy Alan, man. He knows all about synthesizers. He works for Weather Report!” And they go, “Is that the one at 7 o’clock or 11 o’clock?”

DC: [Laughs]

AH: So I went down, met them, and they asked me to do an audition tape. The audition tape was to make the sound of the Starship Enterprise going from Warp 1 to Warp 7. I did it in my little dining room with a Prophet-5 synthesizer. I dialed up the sound, turned it in, and that became the sound of The Enterprise! I hit a home run my first time at bat.

That put me in Star Trek 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 as the Special Sound Effects Creator. Now, there are editors and supervisors and a lot of other stuff, but I was sort of the guy who was in the studio making stuff to feed them. [Making] things that you couldn’t record with a microphone, they had to be made.

DC: Did you cross paths with composer Jerry Goldsmith at all? If so, was there anything you learned from him that inspired you to pursue composing?

AH: One of the engineers for Weather Report was a fellow named Bruce Botnick. He also did The Doors, and he was Jerry Goldsmith’s recordist. So, I knew Bruce, and I got to go down to the first Star Trek scoring session and kind of sneak in the back to watch for a little bit. And there’s Jerry Goldsmith with a full orchestra. I mean, the real Hollywood stuff! I was duly impressed, and it inspired me.

Then, the next Jerry Goldsmith encounter was on Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. I got to sit in the studio; Bruce Botnick’s there, he knows me, and I get invited in. I get to sit with Jerry for like an hour, one-on-one. He’s doing some keyboard overdub, and I got him casually talking.

So, in my book, John Williams and Jerry Goldsmith are like Beethoven and Bach. They’re the best guys that we had at this time. The other guys were good, but these were the guys. So I said, “Jerry, all this great music, where does it come from?” And he goes, “Mahler. He’s my guy.” He admitted that Gustav Mahler was his inspiration! And when you hear Jerry Goldsmith, he’s filtering all the works of Mahler that resonated with him.

You know, there’s a great quote that says, “The average artist plagiarizes, but a great artist steals.” You take it in, and then you make it so that nobody knows where it came from. Put it out, and now it’s your art.

DC: Makes total sense! We’re all influenced by what we absorb, and that’s not always bad. As somebody who is so involved and interested in the tech side of music and sound, where did that come from?

AH: Well, when I was a little kid, I had electric trains. I was taking them apart and putting them back together. My parents were horrified. “This thing costs $100, Alan! You’ve got it all in pieces! Is that going to be put back together!?” I mean, it’s just me.

But the music technology, as an artist, I wanted to know everything. When I played that electric guitar, it was the guitar into the amplifier, through the echo, out to the sound system, and through to the board. I had to know it. Then, I got very active in the music store business, and since I was selling this stuff, I had to know how it worked.

I also had a good relationship with the manufacturers. So, I was friends with Dave Smith from Sequential Circuits from the beginning. I had, like, a serial number 5 Prophet-5 that I ran with the paint still drying. I worked with Bob Moog and Ray Kurzweil and people from Korg and Yamaha as an artist. “You know, you should really add a thing here.” Or, “When I do this, it doesn’t work. Can you fix that?”

And then, the grand finale, I had a thing called the Synclavier system, which was the big giant digital workstand recording studio. It’s like two refrigerator-size racks of gear, and that was, like, The God. The biggest, baddest thing you could get in the day. It was the beginning of digital.

For Star Trek, I made sound effects with synthesizers, but then I’d go, “Well, that’s really good for the Starship Bridge and the electronics, but we need organic sound. We need real sound.” So, I also became very familiar with and used tape recorders. I mean, today, we have digital samples, but then it was tape recorders.

So a tape loop in my world was actually a piece of tape with a little splice on it that ran off the thing and halfway around the room, through the mic stand, and came back the other way. I really made loops. Then, I would re-record those loops to another tape recorder and build up tracks. So tape art was part of my schtick, as well as synthesizers.

DC: OK, I can’t have you here and not ask about your work with John Carpenter. It seems to have been a very symbiotic working relationship from the outside. What are some of the unique things you had to offer, and what did you perhaps learn from him?

AH: Oh, great question. To continue the story, the picture editor from the first Star Trek, a fellow named Todd Ramsay, his next movie was Escape from New York. I had given Todd my music tapes, and at a point, he said, “You know, you should really meet John Carpenter. I think you guys would get along really well.”

So, I had a nice set-up in my dining room studio in a rented house in Glendale, and he came over and hung out for about three hours. I played him some of my music, we talked about stuff, and at the end of it, he goes, “Yeah. Let’s do it.” No agents, no big contracts, no NDAs and force majeure and all that. Just two guys.

He would tell me that doing music for his own movies was like being on vacation. All the stress of making the movie was parked over there, and he could just come over to my house because I had all this stuff. So that was part [of what I offered]. I had all this stuff, and that’s what he loved. He’d just walk in with a cup of coffee and a cigarette and start.

In the beginning, we didn’t have synchronized videotape, but I started right away with a videotape on a VHS deck. We could run the scene, and then sync was to just push play on both of them at the same time. He loved it. He called it an “electronic coloring book.” Before that, he would have to do it with a stopwatch. So, I sort of brought it to the point where the music and the movie started coming together technically. It sped up the process and got us a better product.

The whole synthesizer synchronization and drum machine stuff was on me, the palette of sounds. That was all from my side. It’s like if you’re a painter and somebody hands you a palette with all the colors on it, and now you get to dab your brush and paint some over here and some over here.

The part that I got from him was I got to watch John Carpenter select music for his own movie! He wrote it, he directed it, he edited it, and now he’s sitting down at the final finish line, putting the icing on the cake. He was using his musical talents, and he knew what he was doing. It was great to be there, and I learned a lot.

Everything I learned from him was how to tell stories with music. He’s also tremendously talented in the idea of being simple and minimalist. So, a Jerry Goldsmith or a John Williams do these elaborate orchestral things. Not John Carpenter. It’s just a couple of synths, and we’ll do our thing. And the fact that he wanted to do it with synths was great because it was just me and him in the room. We played the keyboards, the guitars and whatever.

He did most of it because he’s the guy! He knows what he wants, so he’d take the first stroke. Then I’d come back and sometimes fill it in and touch up stuff. As we got farther along, he gave a little bit more of, “Hey, you can do your thing. Why don’t you take care of this? I’ll come back tomorrow and show me what you got.” That was sort of the Prince of Darkness, They Live time.

DC: You two created so many iconic scores together, but is there one that rises to the top in your mind?

AH: The best score we ever did, in my opinion, was Big Trouble in Little China. There are two reasons for that. One, the movie had more scope than a Halloween, right? It went to different places. We had rock-and-roll, Chinese fight music, heroic music, chases, and scary things. So we got to do a lot of different music.

The other thing is, normally, we’d have about six to ten weeks to do the project, but there was a delay with the visual effects. So, the schedule got pushed by a month. Now, I could take things from the end that we hadn’t created in the beginning and put them in the beginning and really produce them.

In addition, there was a technical thing that entered the game called MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface). In the early days, it was patch cables and all this other stuff. But finally, there was a digital interface. You could now play one synthesizer, and that would hit six other ones. So these rich, chocolatey synthesizer textures were built for that one. We also had digital samples and keyboards that had digital recordings of voices, guitars, basses, and violins. We had a real-world digital orchestra on top of the analog synth. That’s why I think it’s the best one.

DC: I’d like to ask you a bit more about the art of collaboration as you appear to be very good at it. Even a casual glance at your resume supports this. What makes a good collaborator, and what have you learned about yourself as a collaborator over the years?

AH: So, I saw this happen a lot with John Carpenter. If a person approaches John and they’re a fan, they get put into the fan box. To me, he was just another guy. He was John Carpenter, so I wasn’t unimpressed, but I wasn’t impressed either. We were on equal levels one-on-one.

Bruce Campbell, when I did Army of Darkness, would come over and really get involved in the sound design. I was the sound supervisor and designer, and Bruce had tapes of stuff. We collaborated and built the sound effects track prior to the movie being finished. That movie had this elaborate visual layering, so that took time, and the movie wasn’t really ready to edit until that was all done. So Bruce came over and hung out with me. He was excited about the sound effects! And he’s just another guy.

It’s the same thing even with directors. I mean, I got to work with Leonard Nimoy and William Shatner! I was never in awe. Not that I didn’t respect them, but I never took the fan position. Good collaborations are when you’re on an equal playing field when you’re one-on-one.

I’m also kind of lazy. So when somebody else comes in the room and is like, “We’re going to do this right now,” I get busy. Otherwise, when I’m by myself, I could easily go get lunch, come back, and then kind of get back to it. We all have those qualities, and that is one I have in my world. But from the creative side, I’m thinking about it the whole time. Whether I’m walking the dog, cutting the grass, or just driving around. I’m constantly thinking. I’m mentally preparing for the day we get on the track and have to run.

Another short story, which I think is good., I was having lunch with Brian Eno, a major synth guy and producer, and he told me a story. He says, “Alan, here’s what I do. I sit down with the band, and we create restrictions with instrumentation and how we’re going to do this. We’re going to restrict what we’re going to do.” And he says, “I do that for two reasons. One, we’re more efficient because we’re only going to use this much.”

In the old days, we had to push and get more out of what we had because we didn’t have the entire universe of possibilities in front of us. We had to get it out of that. And then, “Two, it pushes the artists to make more out of what they’ve got.” He said that was a very useful exercise, and it’s sort of gone away with the world of infinity. The restriction makes a better record, and that’s something from somebody I respect who works with other artists. So consider that when you think you don’t have enough equipment. Forget it. Just use what you’ve got.

DC: You have a brand new score out for the new film From the Shadows that has a ton of familiar names and faces attached to it. First off, it’s pretty awesome how you’ve never stopped working in film and continue to do so.

AH: Nor do I ever intend to stop, so I’m happy to hear that! There’ll be someday when I’m in the studio, and I’ll put the thing on record, and I’ll fall on the keyboard, and that’ll be my last chord. That’s how it’s going to go. [Laughs] I’m taking this life out to the very end. I’m just having too much fun.

DC: Always love to hear that! Tell us a little about how you got involved with From the Shadows and your general approach to the film and the music.

AH: It had already been edited and was in post-production. Ian [Holt] was asking for more of this and that, and he says, “I’d really like to have a John Carpenter-like score for this movie.” And my good friend CeCe Hall [sound designer], who I knew from the first Star Trek, goes, “Well, you know Alan Howarth did all that stuff with him. Why don’t you give him a call?”

Knowing that they had a Carpenter-esque wish, I looked at it and thought, “In some ways, this is kind of like The Fog.” Except here, there are things coming from another dimension, and I thought, “That would work.” And I jumped in.

It’s also interesting that in the last four or five scores I’ve done, they’ve asked me to use these things [points to analog synths behind him] and not all the digital sample stuff. “Do what you did with John Carpenter for me.” That’s a style. Stranger Things incorporated this already, too. So we kind of wrote the book, and to ask me to go back to the book and write some more, well, that’s easy. It’s a no-brainer. That was the start of it.

Then, I had other stuff that I had [previously] created because they came in sort of at the last minute, so there wasn’t a lot of time. It was some ideas I had from other things that I had to kind of lean on. Normally, you have six to ten weeks, and I had three weeks. So, it was an accelerated process. I remember when I was in film school at UCLA, the instructor, who was a great arranger, said, “Here’s what you do. Take all your ideas. You never know when you’re going to need them. If you’ve got ideas, just put them in a drawer. Then someday, you can reach in that drawer when you need stuff.” And that’s how we did it.

DC: You are so full of tips and tricks and really seem to absorb and take advice from others to heart. That’s really smart and seems to have truly benefited you.

AH: That’s why I’m still sitting here on Earth in the year 2023. I’m experiencing life, and I learn lessons. If you don’t learn lessons, you’re going to just do it again and again until you learn to move to the next thing.

I just had a birthday in August, and I turned 75. And the way I look at it, let’s assume I’m going to live to be 100. I’m actually going to make it to 150, but for the purposes of math, we’ll call it 100. So, I just got into the fourth quarter of my life game. In the fourth quarter of a football game, you got your score, you know your opponents, you know what you’re up against, but you want to play to win. You pull from all your lessons, and you start getting more focused. I want to make sure that in the end, everything I wanted to get done got done successfully.

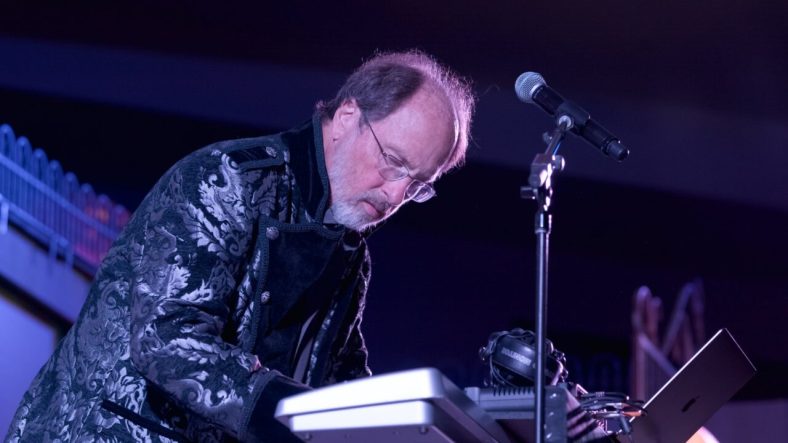

DC: It has been really cool to see you and composers like Fabio Frizzi, Joseph LoDuca, and John Massari performing at cons and releasing reimagined versions of your work. What’s the inspiration behind stepping onto the stage, and what has it been like revisiting these scores?

AH: Well, every convention, I try to get them to let me play. It’s a lot more effort than just sitting at a table and signing stuff because I have to bring the gear and schlep it, but I get to be me. Flashback Weekend was the most fun I’ve had in a long time because I was sort of the Saturday night featured act, and I filled a room with 300 people. That energy! I mean, I’m an old rocker. I play in front of people, and that inspires me to play.

The band Weather Report I worked for, they’re improvisational. That’s burned into me. Even when I score, I don’t write anything down. I just start playing. So I’ve got the clips and video art, the tracks playing, and I get to jam over that live with stuff I make up on the fly, and it’s never the same.

At a certain point, you’re done, right? That’s what we did 30 to 40 years ago. The fact that we’re even talking about it is amazing. It’s withstood the test of time and is still relevant. You can imagine all the stuff that nobody cares about. So, for it to come into this next generation’s psyche, now, we rediscover the artist part.

This is how it goes as a musician, a sound designer, or even an editor. I’ve worked with the greatest editors in the world. You know, a guy like Michael Kahn who did all the Spielberg stuff. When I did Poltergeist, I was sitting in front of all these guys. I was in a room with Steven Spielberg, Michael Kahn, and Frank Marshall. Again, you be cool and don’t be a fan. You just write your notes. I’ll give you another short story.

So I’m working on Poltergeist as Mr. Sound Design, and it comes to the point where we’re talking about the sound of Carol Anne’s voice. She’s not in the scene, but we’re going to hear her voice come from another dimension. So I look at Spielberg, and I go, “Well, Steve. What are you thinking?” He looks at me very seriously and goes, “Earth to Venus.” So I write down “Earth to Venus.” I have no idea what he’s talking about, and I go out in the hallway and start to sweat. If I don’t get this right, I’ll be excommunicated. I’ll never work again. The pressure is cranking up, and I’m trying to be cool.

I try all kinds of stuff, and it’s not working, and the clock’s running. Then, I get in the car to drive my tapes to Paramount to be transferred to mag, and on the radio comes Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love.” There are two areas in the song where there’s a psychedelic breakdown, and there’ wa’s this effect on Robert Plant’s voice. You heard his voice quietly before you actually heard the line. That was it! Earth to Venus! He wanted to hear it in the distance, approaching from another dimension and coming in. So that was my inspiration.

I went back to the studio, took the little girl’s voice, put it on a tape recorder backward, played it into reverb, and then recorded that with varied speeds on the tape. Then I flipped it around and did it again. That was the solution. That’s the defining moment that I put into the world of sound effects— reverse reverb.

DC: From Led Zeppelin to Carol Anne. I never would have connected those two, but I love that they are connected.

AH: You don’t know where creative things come from. You’ve got to keep all your channels open, watching and waiting for things to stimulate.

DC: Do you feel like you have a stage persona when you perform? I ask because I’m obsessed with the fabulous jacket you often wear on stage.

AH: I was actually at Midsummer Scream when I first wore the jacket. I was talking to Christopher Young and Richard Band, and they said, “Nice jacket, man.” And I said, “Well, here’s how I look at it. When you’re in church, the priest puts on his vestments to get ready to do the thing. This is my vestments. I’m going to dress up now as a horror movie composer, go up on stage, and have X number of people looking at me.”

Now, that part doesn’t bother me. I’m the same person talking to you right now as I am up there, but there’s a ceremony. It’s a concentration and the idea that we’re going to do “this” now versus just hanging out and talking. It’s very focused, and it’s a show! And that’s fun to me. I never get nervous, it’s just not part of the deal. That’s from playing in bands. I mean, when you open for The Who in front of 15,000 people, you can’t be thinking about anything except that you better be playing really good.

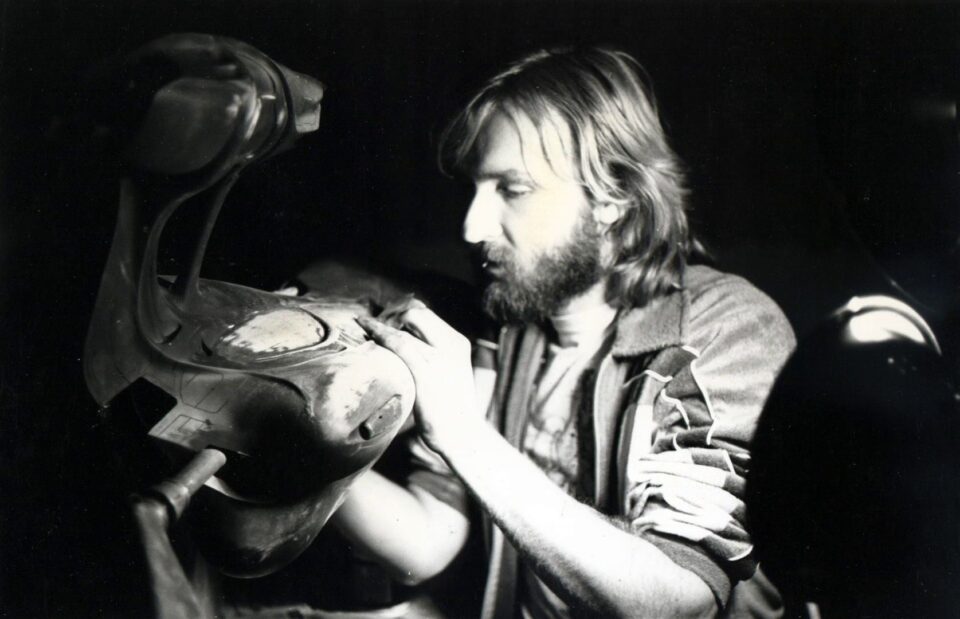

DC: Before we go, there’s a film on your resume that I’ve always been intrigued by—Battle Beyond the Stars. It involved many early career talents, including James Cameron, James Horner, Gale Anne Hurd, and yourself. What do you remember about working on that film?

Alan Howarth: As post-production, I came in for music and sound. James Horner and I actually met each other in that movie. I got there because I had done Star Trek. It was easy for me to come from Star Trek, sort of, downstairs into the basement with a Roger Corman production. And that’s what Roger Corman did. He provided an entry for talented people. He didn’t pay crap, but you accepted that because you got an opportunity. You got to show your stuff and meet other people. That all worked.

For James Horner, that was his first orchestral score, where he pulled it together to get enough of an orchestra to show what he could do. James Cameron, he took his shot there. Actually, Cameron was also on Escape from New York as a graphic artist. So, he was just emerging and finding his way into the business. Before that, he was a truck driver or something like that. To all the aspiring folks that want to do this, it doesn’t matter if you’re a truck driver, a worker at Walmart or Burger King. You have to follow your passion. And there’s only one rule—Never give up.

From the Shadows is available now on VUDU. It will be widely available on VOD on October 29, 2023. Additionally, you can find lots more info about Howarth and his music (including vinyl releases) on his websites, alanhowarth.com and naturalresonance.net.

Categorized:Interviews